Can Renewables Become More than a Sideshow?

The great electrification projects of the 19th and 20th centuries created a world where (at least in developed countries) electricity is as common as clean water. They also created a world addicted to fossil fuels. Globally, over 40 percent of electricity is generated from coal and another 20 percent from natural gas, releasing billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year.

The consensus that carbon dioxide is changing the climate in dangerous ways has convinced most politicians, scientists, and industrialists that we must reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. The U.S. Congress is currently considering a bill that calls for a 17 percent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions below 2005 levels by 2020.

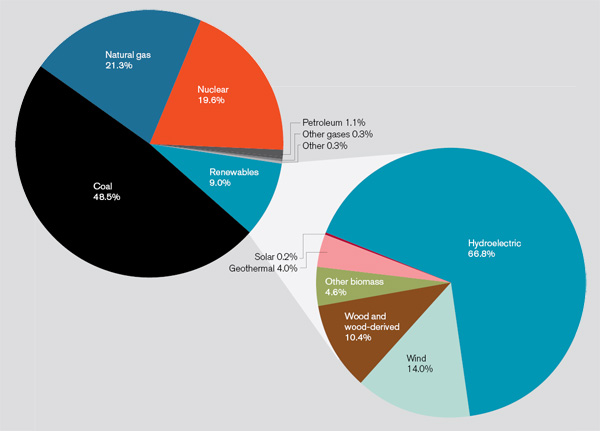

But renewable power represents only about 9 percent of U.S. electricity generation. Solar power is responsible for a scant 0.02 percent. The reality is that renewable power and other alternatives to fossil fuels, including nuclear, remain too expensive to compete with coal and natural gas. Coal costs about two to four cents per kilowatt-hour; electricity from photovoltaics costs about five times that. Even with legislative efforts to increase the cost of emitting carbon, for the foreseeable future the imposed cost of emissions will probably to be too low to drive substantial investment in alternatives. Compounding the problem, the worldwide credit crisis that began last fall effectively halted construction of new types of power plants, many of which cost hundreds of millions to build.

Renewables are unlikely to end our reliance on fossil fuels within the next 20 years. But that is no reason for inaction. Smarter policy decisions and technological innovation can reduce what our energy sources contribute to climate change. Legislation that puts a price on carbon emissions is essential, but it must be based on a full accounting of environmental and economic costs. It is also critical that government and industry make a long-term commitment to funding energy research. The goals are clear: a smarter grid that can handle intermittent power sources and distribute and store electricity more efficiently; a realistic and safe approach to carbon sequestration; and lower-cost photovoltaics that could finally fulfill the immense potential of solar power.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.