A Fuel-Sipping Engine

A research project in the UK has developed a gasoline engine that it claims can reduce fuel consumption by 15 percent without losing power.

The key to the new design is the way in which fuel and air are separately introduced into the engine cylinders. By experimenting with different regimes for directly injecting fuel while varying the opening and shutting the air inlet valves, the researchers say they have achieved the major breakthrough in performance–and developed a “concept-car engine” that is gaining interest from big auto makers.

The aim of the project, a collaboration between two leading car engine development companies, Lotus Engineering and Continental Powertrain, and two universities, Loughborough and University College London, is to reduce losses caused by the engine throttle. In conventional engines, the throttle is kept partially closed except during full acceleration, obstructing the flow of air and reducing the pressure and density of the air that enters the cylinder. This forces the engine to work harder to pull air into the cylinder. That wasted energy can be saved by controlling the mass of air that enters the cylinder not with the throttle, but by varying the timing of valve openings at each cylinder. This also enables engines to be made smaller and more efficient.

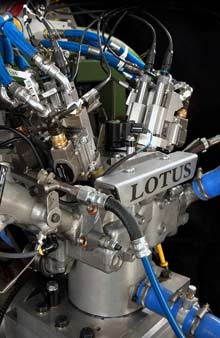

Such adjustments aren’t possible with conventional variable-valve engines, which use mechanical controls that restrict their operation. But Lotus Engineering has developed a hydraulic system that it says enables “complete control” of the timing, duration, and lift of the valves. The researchers concluded that the best configuration of valves was four for each cylinder, two for air intake and two for exhaust. According to the company’s principal engineer, Graham Pitcher, engine output could be controlled by closing one intake valve and slightly opening the other.

Another important difference from previous designs is that the fuel injector is positioned centrally in the head of the cylinder, rather than in the side. This enables fuel and air to mix better, though it means that the injector is located at the hottest part of the engine and so requires improved water flow to keep it cool. An added benefit of better combustion is lower amounts of unburnt fuel in the exhaust, resulting in fewer hydrocarbon emissions.

Lotus Engineering and Continental Powertrain have already adopted the technology in a low-carbon concept car. A three-cylinder, 1.5-liter engine based on the combustion concept has been fitted to the Opel Astra and shown to cut carbon dioxide emissions by 15 percent compared to the Astra’s standard, 1.8-liter, four-cylinder engine. At the same time, the concept car produces a 36-percent increase in torque and a 14-percent increase in power output.

According to Geraint Castleton-White, power-train leader at Lotus Engineering, the outcome is a car that emits 140 grams or less of carbon dioxide per kilometer. In 2007, cars sold in Europe averaged 158 grams of carbon dioxide per kilometer; proposed legislation in the European Parliament would require cars to meet standards of 130 grams per kilometer by 2012.

“We have had tremendous interest from manufacturers around the world and the concept will be in production in the future,” says Castleton.

The prototype engine is more cost effective than other direct-injection, “lean burn” engines, because it avoids the need for expensive equipment to trap nitrogen oxides, he says.

John Heywood, professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, isn’t surprised by the improvements. “There has been a nearly linear improvement in performance of internal combustion engines over the last couple of decades or so,” he points out. “We need to pursue all possibilities that look promising.” But he suggests there are other potential ways of increasing engine efficiency, such as reducing friction, which might end up being more cost effective. “There are questions over the long-term market attractiveness of variable-valve technology,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.