50 Smartest Companies 2014

50 Smartest Companies

- 1

Illumina

- Headquarters San Diego, California

- Industry Biomedicine

- Status public

- Years on the List 2010 , 2013 , 2014 , 2015 , 2016 , 2017

Summary

Almost 25 years after the Human Genome Project launched, and a little over a decade after it reached its goal of reading all three billion base pairs in human DNA, genome sequencing for the masses is finally arriving. It will no longer be just a research tool; reading all of your DNA (rather than looking at just certain genes) will soon be cheap enough to be used regularly for pinpointing medical problems and identifying treatments. This will be an enormous business, and one company dominates it: Illumina. The San Diego–based company sells everything from sequencing machines that identify each nucleotide in DNA to software and services that analyze the data. In the coming age of genomic medicine, Illumina is poised to be what Intel was to the PC era—the dominant supplier of the fundamental technology.

Illumina already held 70 percent of the market for genome-sequencing machines when it made a landmark announcement in January: using 10 of its latest machines in parallel makes it feasible to read a person’s genome for $1,000, long considered a crucial threshold for moving sequencing into clinical applications. Medical research stands to benefit as well. More researchers will have the ability to do large-scale studies that could lead to more precise understanding of diseases and help usher in truly personalized medicine.

Illumina was relentless in getting to this point. When CEO Jay Flatley joined the company in 1999, it was a 25–person startup that sold microarray chips, which were useful in examining specific spots on the genome for important variations. But while the market grew relatively fast, competition was tough. In 2003, for example, Illumina had $28 million in revenue and a net loss of $27 million. Making matters tougher, the potential for microarrays seemed limited once more comprehensive sequencing technology began to improve quickly. In 2006, when a company called 454 Life Sciences was months away from the first rapid readout of an individual human genome (that of DNA scientist James D. Watson), Flatley knew Illumina had to have a sequencing technology of its own, and he had a choice: build it or buy it. “We had an internal development program, but we were also looking at anyone in the market that already had a sequencing technology,” he says now. Ultimately he settled on buying a company called Solexa.

Solexa took advantage of a novel way of sequencing, known as sequencing by synthesis, that was 100 times faster than other technologies and correspondingly cheaper, says Flatley. But it was a small business, with just $2.5 million in revenue in 2006. After Illumina provided the global distribution Solexa needed, “we built it into a $100 million business in one year,” he says. “It was an inflection point for us. We began this super-rapid growth.”

The deal also turned out to be a turning point for Illumina’s competitors, which quickly fell behind technologically. Roche, which bought 454 Life Sciences in 2007, announced last October that it would shutter the company and phase out its sequencers. Complete Genomics, another competitor, cut jobs and began looking for a buyer in 2012; last year the Chinese company BGI-Shenzhen bought it, although Illumina made a failed bid for it as well.

The Solexa deal was far from the last time that Flatley transformed Illumina by buying the technology he thought it needed. Another pivotal point came last year, when the company bought Verinata Health, maker of a noninvasive prenatal sequencing test to identify fetal abnormalities. That gave Illumina a service that consumers can buy (through their doctors), in a market that could be worth billions of dollars in revenue.

Since 2005 Illumina has spent more than $1.2 billion on acquisitions. But it would be a mistake to dismiss the company as just a deep pocket. Illumina has a knack for improving the technology of companies it buys, says Doug Schenkel, managing director for medical technology equity research at Cowen and Company. When Illumina bought Solexa’s sequencing technology, Schenkel says, it was considered inflexible and was thought likely to hit a “ceiling”—after which it could probably not be improved further—within three years. “Illumina took that technology and, with innovation and investment, has made it flexible enough to not only dominate existing markets but open up multiple new opportunities,” he adds. “Even today—six years later—the ceiling is still at least three years away.”

Illumina’s soup-to-nuts strategy—of providing fundamental sequencing technologies as well as services that mine genomic insights—appears to be a winner as genomic information begins to touch the practice of medicine and enter everyday life. Illumina already has an iPad app that lets you review your genome if it has been analyzed. “One of the biggest challenges now is increasing the clinical knowledge of what the genome means,” Flatley says. “It’s one thing to say, ‘Here’s the genetic variation.’ It’s another to say, ‘Here’s what the variation means.’” Demand for that understanding will only increase as millions of people get sequenced. “We want to be at the apex of that effort,” he says.

- 3

Google

- Headquarters Mountain View, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status public

- Years on the List 2010 , 2011 , 2012 , 2013 , 2014 , 2015

Summary

When it comes to developing software, few companies can match Google’s prowess. It doesn’t just have the most popular search engine. Chrome is the most widely used Internet browser. Gmail, Calendar, Spreadsheets, Docs, and Presentations are legitimate alternatives to Microsoft Office. Picasa, Google’s free photo management software, might be as good as anything from Apple. Android dominates the phone and tablet landscape. Google Maps is becoming the best navigation program on any device.

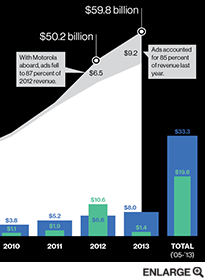

And yet by one important measure, Google hasn’t been innovative enough. The vast majority of its revenue comes from ads—the ones in search results and the ones that Google pushes out to thousands of websites. These were amazing innovations when Google developed them back in 2001 and 2002. But Google’s many efforts to develop additional ways to make money haven’t gone very far.

Perhaps Google’s most public failures have been in consumer electronics. Do you remember Google TV? The Nexus One? The Nexus Q? If you do, it’s probably not because you bought one. Google acquired Motorola Mobility for $12.4 billion in 2012 in an effort to finally build products that consumers wanted to buy. But Motorola’s market share fell on Google’s watch; the deal soured so fast that Google is now selling off most of Motorola to Lenovo. In the end Google will have spent about $3 billion to get a chunk of Motorola patents.

Google’s problem is straightforward: its culture is rooted in building software, giving it away, and improving it over time—all with little in the way of advertising or marketing. Selling stuff requires the opposite—persuading customers that the product for sale is finished and perfect in every way.

So why can’t Google just accept the market’s judgment of its strengths and weaknesses and stop wasting shareholders’ money trying to expand the revenue base? Because even though there is every indication that Google’s advertising business will keep growing for years to come, nothing guarantees that it will dominate forever. Something could come along and do to search ads what search ads did to TV and newspaper ads.

That is why Google still hopes to compete with the likes of Apple in consumer electronics. And it’s not too late, especially with Google’s $3.2 billion purchase of Nest Labs in January.

Of course, acquisitions are rarely magic bullets, as Google can attest. And look at the business Nest is in: it makes home thermostats and smoke alarms, which, to be kind, have been on the trailing edge of innovation. But that’s what makes this purchase interesting. Nest has transformed these moribund categories with clever products that learn their users’ preferences and feel like things you would buy in an Apple store, which in fact is one of the places they are sold. Even though Nest’s thermostat costs $250, market analysts estimate that consumers have been buying more than 50,000 units a month.

What really made the Nest deal attractive, however, was the people. Nest’s CEO and cofounder is Tony Fadell, the former Apple executive who was critical in that company’s rebirth. He helped build and design the iPod, and then he helped conceive and build the iPhone. Fadell and cofounder Matt Rogers, who was also one of the early iPhone engineers, have hired roughly 100 of Apple’s top engineers and marketers, according to public profile data on LinkedIn. They made Nest one of the largest repositories of ex-Appleites in Silicon Valley.

Indeed, buying Nest could be Google cofounder Larry Page’s most important deal since he became CEO in 2011. Motorola didn’t bring much expertise in design or marketing, whereas Fadell spent a decade working for Steve Jobs, giving him insights he used to turn Nest into an overnight success. Now he reports to Page, and Google might finally produce a new kind of innovation.

- 5

Salesforce.com

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

2,150

number of business apps in Salesforce's online marketplace - 7

BMW

- Headquarters Munich, Germany

- Industry Advanced manufacturing

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

2020

when BMW expects to begin selling cars that are autonomous on highways - 8

Third Rock Ventures

- Headquarters Boston, Massachusetts

- Industry Biotech

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

Summary

The path to greatness in biotechnology runs through a vale of tears. Mark Levin wants to remember that.

So once every few months the 40-person staff of Levin’s venture capital firm, Third Rock Ventures, gathers silently to listen. Their speaker last September was Peter Frates, a 29-year-old former captain of the Boston College baseball team. In a voice slurred by spreading paralysis, Frates recalled how his doctors told him, “You have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” and then sent him home. There was nothing to do.

BIOTECH DATA FROM PHRMA, ERNST & YOUNG

BIOTECH DATA FROM PHRMA, ERNST & YOUNGInventing a treatment for ALS is immensely challenging. Most drugs fail. Even so, Third Rock intends to try. Since 2006, Levin and cofounders Kevin Starr and Bob Tepper have backed 32 companies that have 25 products in human trials. Its newest venture, Voyager Therapeutics, is typically ambitious: it will have $45 million to try to develop a gene therapy for nervous-system disorders such as ALS. Levin himself will be the CEO.

“The big difference is they go in on their own, and they go in big,” says Amber Salzman, a biotech executive whose son was born with adrenoleukodystrophy. That heartbreaking inherited disease is now in the sights of Bluebird Bio, a gene therapy company that went public last June—one of three IPOs for Third Rock startups last year.

Levin grew up in St. Louis, son of a small-time entrepreneur who sold shoes. He bought a doughnut shop and worked in process engineering at Miller Brewing before making a name as a dealmaker in California’s early biotech scene. “That was a crazy time, when anything was possible,” he says.

A similar spirit pervades Third Rock’s warren of offices in a Boston brownstone. A gumball machine at the entrance declares it an entrepreneurial space. Slogans on the wall say “Do the right thing” and “Make them raving fans.” Levin, immensely rich from companies he’s sold, comes to the office in outrageous jewelry and neon sneakers.

Third Rock has a unique approach to sizing up emerging technologies. The firm cultivates a long to-do list of ideas, like one for “personalized vaccines” and one for a “molecular stethoscope.” It then spends three or four years studying the science and the markets, and seducing the world’s leading experts to sign on.

“Some people can spot what is going to be extraordinary in five or 10 years,” says Gregory Verdine, a chemistry professor who was lured out of a tenured position at Harvard to run another Third Rock company, Warp Drive Bio. “And then there are those who can imagine it and actually build it.”

Verdine puts Levin in the category of great leaders, citing his ability to attract the best people to his causes. He is “an extraordinarily empathetic person,” Verdine says, “who wants to leave his mark on biotech.”

“We’re always listening to the experts, watching them, hearing them talk about the genetics, the biology, or what’s happening in chemistry. You can just feel it if we are on the edge of something. It’s a visceral experience.”

—Mark Levin - 13

Cree

- Headquarters Durham

- Industry Advanced manufacturing

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

Summary

Opportunity: Driven in part by new government regulations on energy efficiency, LED lighting is increasingly replacing both incandescent and fluorescent lighting in everything from desk lamps to streetlights. LED lighting, which uses semiconductors to produce the illumination, offers various benefits: it’s more energy efficient, a bulb lasts many years, and it’s dimmable. What’s more, thanks to advances in the technology over the last decade, LEDs produce light of reasonably good quality. But many consumers and businesses have been reluctant to switch over to the new technology. That’s partly because initial products were ungainly and because LED lights are more expensive than incandescent bulbs, a technology that dates back to Thomas Edison.

Innovation: Cree started out as a supplier of components to other LED makers. Two years ago, however, unsatisfied with the quality of LED-based bulbs made by those established manufacturers, engineers at Cree resolved to design and make their own. Last year, Cree released a consumer product with the familiar shape and light quality of an old-style filament bulb, priced at under $14 for the equivalent of a 60-watt bulb; LED bulbs had been selling for more than twice that just a few years earlier. The company has begun selling its bulbs at Home Depot.

Cree’s LED bulb competes directly with ones from lighting giants such as General Electric, Philips, and Osram Sylvania. But Cree now sells about $500 million worth of LED lighting annually and has nearly 10 percent of the market in North America, according to the Carnotensis Consultancy.

Inside each bulb is the source of Cree’s technology advantage: a series of LEDs, each about half the size of a typical pencil eraser. Cree makes them on silicon carbide wafers, allowing the company to produce more light from an LED chip than competitors that use sapphire substrates. But price, ultimately, is what drives consumers. And Cree predicts it will be able to match traditional lighting on price in the not-very-distant future.

- 14

Box

- Headquarters Los Altos, California

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

1,000

number of third-party mobile apps that work with Box - 16

Wal-Mart Stores

- Headquarters Bentonville, Arkansas

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

1 billion

Walmart.com page views in first five days of holiday season - 19

Kaggle

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

144,000

number of registrants for Kaggle data-analysis competitions - 20

Second Sight

- Headquarters Sylmar, California

- Industry Biotech

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

74

number of people who have gotten the Argus II implant - 22

Kickstarter

- Headquarters New York, New York

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$962 million

money pledged onsite for 55,000 projects - 23

Hanergy Holding Group

- Headquarters Beijing, China

- Industry Energy

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$1.2 billion

onetime value of Miasole, a solar company that Hanergy bought for $30 million - 25

1366 Technologies

- Headquarters Bedford, Massachusetts

- Industry Energy

- Status private

- Years on the List 2010 , 2011 , 2014

Summary

The first thing to know about 1366 Technologies is that it has survived. Over the last three years, a long list of solar-power manufacturers have gone out of business, including BP Solar and startups Abound Solar and Solyndra. Not only has 1366 managed to remain afloat through this period, but it has prospered, in a deliberate and methodical way.

Last year the company opened a demonstration-scale factory to produce silicon wafers, a critical component in the most common type of solar cells. If all goes well, early next year it will break ground on a much larger factory financed in part by a federal loan guarantee it secured in June 2011, a few months before Solyndra infamously went bankrupt.

CEO Frank van Mierlo is confident that the failures of solar manufacturing are yesterday’s story. He beams with pride as he shows a visitor around the company’s factory in suburban Boston. Although it’s modest compared with a commercial plant, the many pieces of equipment underscore the investment required to make solar cells.

One room, though, is strictly off-limits to outsiders. In it are two custom–built furnaces that produce thin six-inch-square wafers directly from molten silicon. The final wafers are identical to those made in today’s conventional solar factories, where they are cut from ingots. But 1366’s machines simplify the traditional manufacturing process into one step, slashing costs by more than half. That’s important, since silicon wafers account for about 40 percent of the cost of today’s solar panels, and manufacturers are hungry for even tiny cost reductions.

The heart of the technology is a dishwasher-size machine that freezes the molten silicon into wafers. Chief technology officer Emanuel Sachs, a former professor at MIT, demonstrated the concept with a bath of liquid tin. He then adapted the technology to small silicon wafers, and finally to wafers of industry-standard size. The company’s machine now turns out more than 1,000 wafers a day.

Sachs also invented the technology behind Evergreen Solar, which went bankrupt in August 2011. Unlike Evergreen, though, 1366 chose to supply components for solar panels to other manufacturers, rather than trying to sell completed panels itself. This reduced the business risk of getting a new technology accepted and made it less expensive to scale up the manufacturing process.

By the end of next year, 1366 intends to have 50 machines at its planned $100 million factory, producing enough wafers for 250 megawatts of solar power. By then, analysts estimate, the market for solar will be gigawatts bigger than it is today. And the prospects for solar power could be brightening.

- 27

Evernote

- Headquarters Redwood City, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$45

cost of an annual subscription to Evernote Premium - 29

GitHub

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

10.7 million

number of repositories of shared software on the site - 30

Xiaomi

- Headquarters Beijing, China

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014 , 2015

Summary

Steve Jobs jolted the mobile-phone business by introducing a device that everyone had to copy. Now his unabashed admirer Jun Lei is shaking up the enormous Chinese market with smartphones that cost much less than comparable devices.

XIAOMI DATA FROM CANALYS, XIAOMI

XIAOMI DATA FROM CANALYS, XIAOMILei is founder and CEO of Xiaomi, which is just four years old but already one of the top six smartphone vendors in China. It entered the business in 2010 by releasing a custom Android operating system, known as MIUI (pronounced “me UI”), whose interface looked a lot like the iPhone’s. It was hugely popular among enthusiasts who love to modify a phone’s functions. A year later, Xiaomi began selling a series of phones that had high-end specs but sold for roughly half of what rival devices were going for in China.

One reason the prices are so low is that Xiaomi (pronounced “zho-me”) sells at or near cost and makes its money when customers pay for its cloud-based services, such as messaging and data backup. The company is also skillful at timing its sales. It presells a very limited number of devices, which invariably sell out, attracting more interest. By the time the later buyers get their devices, manufacturing costs have declined significantly for Xiaomi.

Lei has cultivated a Jobs-like image, all the way down to his personal wardrobe and product announcements. His fans call him “Leibs” (a combination of Lei and Jobs), though his detractors also use the term in mockery. Regardless, his company is getting itself in position to sell a big chunk of the billion Android phones expected to flood the developing world in the next few years as prices keep falling.

“Even a pig can fly if it sits in the right spot during a whirlwind.”

—Jun Lei - 31

Oculus VR

- Headquarters Irvine, California

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

21

age of founder Palmer Luckey - 32

Qihoo 360 Technology

- Headquarters Beijing, China

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

$12 billion

Qihoo's market capitalization - 36

Jawbone

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

28

countries where the Up fitness band is sold - 38

Valve

- Headquarters Bellevue, Washington

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

65 million

number of people using Valve's game-distribution network - 39

Genomics England

- Headquarters London, United Kingdom

- Industry Biotech

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

100,000

number of genomes the company hopes to sequence in five years - 40

D-Wave Systems

- Headquarters Burnaby, Canada

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

30 minutes

time it took in one study for a conventional computer to solve a problem that D-Wave's machines handled in less than half a second. - 41

Siluria Technologies

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Energy

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

Summary

Opportunity: Making gasoline from natural gas rather than oil could cut its cost in half. Such a technology could also help make plastics far cheaper. While oil costs around $100 a barrel, natural gas sells in the U.S. for the equivalent of about $20 a barrel and is likely to remain much cheaper than oil for some time: it is estimated to be between two and six times more abundant than oil, and technologies like hydrofracking have led to a surge of production from unconventional sources like the Marcellus Shale in the eastern United States. Equally important, natural gas is more evenly distributed around the world than petroleum. The United States has ample supplies thanks to shale deposits, but so do China, many parts of Europe and South America, Australia, and South Africa. Making gasoline and commodity chemicals from natural gas rather than petroleum could help free the rest of the world from the political and economic stranglehold of the large oil-exporting nations.

Innovation: The goal of Siluria, a Silicon Valley startup fueled with $63.5 million in venture funding, is both audacious and simple: create a process that efficiently uses natural gas, rather than petroleum, to make ethylene and gasoline. The challenge is the chemistry. It’s possible to use catalysts to make these products out of methane (the main ingredient in natural gas), but an efficient industrial process has eluded chemical engineers for decades.

Siluria thinks it can succeed where others have failed, not because it understands the chemistry better but because it has ways to rapidly make and screen potential catalysts. The company built an automated system that can quickly synthesize hundreds of different catalysts at a time and then test how well they convert methane into ethylene.

It works by varying both what catalysts are made of and their microscopic structure. Making a catalyst in, say, the shape of a nanowire changes the way it interacts with methane, and this can transform a useless combination of elements into an effective one.

Siluria says the catalysts produced at its pilot plant in Menlo Park, California, have performed well enough to justify building two larger demonstration plants—one across San Francisco Bay in Hayward that will make gasoline, and one in Houston that will make ethylene. The company hopes to prove that the technology will work at a commercial scale and can be plugged into existing refineries and chemical plants.

Siluria can’t tell you exactly how it’s solved the problem that stymied chemists for decades—if indeed it has. Because of the nature of its throw-everything-at-the-wall approach, it doesn’t know precisely how its new catalysts work. All it knows is that the process appears to.

- 42

Kaiima Bio-Agritech

- Headquarters Moshav Sharona, Israel

- Industry Biotech

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$65 million

investment raised in recent round - 43

Datawind

- Headquarters London, United Kingdom

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$38

price of its cheapest tablet - 45

Upworthy

- Headquarters New York, New York

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

Summary

Upworthy is one of the fastest-growing websites ever, despite producing only minimal original material. Instead, Upworthy highlights videos that people have posted online about gay marriage, health care reform, racial prejudice, gender equality, and other subjects that interest the site’s liberal curators. The founders—Eli Pariser, who had led the left-wing political group MoveOn, and Peter Koechley, former managing editor of the satirical publication the Onion—started the site to help progressive-friendly content spread virally online, even if that means coöpting some sensational tactics from sites that propagate videos of cute cats. They spoke to MIT Technology Review’s deputy editor, Brian Bergstein.

Were you surprised at how quickly Upworthy got this big?

Pariser: We were blown away. We honestly never would have dreamed that the site would be as big as it is.

Koechley: A lot of people thought it was unlikely that there were 50 or 60 or 70 million people out there who wanted to watch videos about meaningful social issues.

Describe Upworthy’s system for making things go viral.

Pariser: There are hundreds of millions, if not billions, of videos posted every month, and our curators are looking for the several hundred that are very meaningful about some important topic and very, very compelling. We have various tools that our curators use, but ultimately it comes down to human judgment and their ability to find videos or charts or graphics that just blow them away.

Then they write headlines that have become an Upworthy signature. Your headlines are filled with superlatives—”the biggest,” “the worst,” “the most horrifying”—and tell readers that clicking the link will change their lives.

Pariser: Generally [the curators] write 25 or so headlines and then pick four to try out. And then sometimes they’ll take a couple rounds of that. We think of it kind of like a comedian playing Duluth before you go to New York, working out the material and what people are laughing at.

Koechley: Headlines are a way to get somebody to watch a seven-minute video about depression or a 12–minute video about climate change. If you said “This is a 12–minute video about climate change,” you just know that people won’t click through. But if you actually bring out the stuff that speaks to their curiosity and their interest, you can connect people with ideas that they really love and enjoy.

You’ll have to vary the tone if you want to keep standing out, though. Upworthy–style headlines are everywhere on the Web now.

Koechley: Totally. The number of new directions and formats and ideas that we’re testing every day are legion.

There have been hardly any ads on the site. How will you make money?

Pariser: We’ve mostly been focused on building our community so far. We’re testing a number of revenue options now, and we’re liking the underwriting model, where a foundation or similar group funds our editorial work in a specific topic.

Given that Eli wrote a book called The Filter Bubble, which decries how the Internet often limits people to information they agree with, it’s disappointing that Upworthy repeatedly covers the same topics and doesn’t seem to challenge liberal assumptions. You guys are playing it safe.

Koechley: I think the first problem we were trying to solve is: how can we go from people spending zero minutes a day thinking about important societal issues to spending 10 minutes, or 20 minutes, or five minutes? That said, one of the things we’re planning for this year is we’re choosing topics that we haven’t gone all that deeply into. So we have a partnership with the Gates Foundation to go a lot deeper on global health and poverty.

We’ve now built a platform that is going to allow us to take on lot of really interesting [opportunities]. Challenging the audience to think in different ways or challenging their currently held beliefs is certainly one of those that we think is interesting.

“If you said ‘This is a 12-minute video about climate change,’ you just know that people won’t click through. But if you actually bring out the stuff that speaks to their curiosity and their interest, you can connect people with ideas that they really love and enjoy.”

—Peter Koechley - 46

LG

- Headquarters Seoul, South Korea

- Industry Computing & Communications

- Status public

- Years on the List 2014

30 percent

growth in LG's mobile phone business in 2013 - 47

Expect Labs

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

8

number of people who can participate in a conversation through the company's MindMeld app - 48

AngelList

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

$1 billion

amount startups have raised through the site - 49

Arcadia Biosciences

- Headquarters Davis, California

- Industry Biotech

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

50 percent

amount of nitrogen fertilizer needed by Arcadia's rice, compared with conventional strains. - 50

Ripple Labs

- Headquarters San Francisco, California

- Industry Internet & Digital Media

- Status private

- Years on the List 2014

Summary

It’s a moneymaking scheme a child might suggest: get rich by inventing a new form of money. All the same, Chris Larsen, CEO and founder of Ripple Labs, is getting other people to play along with him. And they aren’t just Silicon Valley investors. People are using Ripple’s digital cash to exchange traditional paper currencies.

Ripple’s currency is modeled on the digital cash Bitcoin, which has boomed and sometimes busted in value over recent years (see “Show Me the Bitcoins”), and both use similar cryptography to prevent fraud. But while Bitcoin is designed to be used like regular currency to buy things, Ripple’s cash, known as XRP, is intended to make many foreign exchange transfers faster and less expensive.

Traditionally, a person who has Burmese kyats, for example, and needs to send money to someone in U.S. dollars has had to wait days for the transaction to clear, incurring sizable fees in the process. That’s because international money transfer systems rely on centralized, decades-old systems to verify that payments are valid. But banks—or new, low-cost startup services—could use Ripple’s technology to sidestep those systems. They would convert the payer’s kyats into XRPs and then use the Ripple protocol to automatically find a partner willing to convert those XRPs into dollars, completing the deal almost instantly. A financial company might choose to hold a stash of XRPs of its own to make such transfers easier.

Larsen hopes this technology will stimulate international commerce and make it cheaper for expatriates to send money back to their families in poor countries. (The World Bank estimates that in 2012, almost 12 percent of the $60 billion in such remittances to African countries was swallowed by transaction fees.) Indeed, Ripple reports that transfers from Europe to China already make up a significant portion of the roughly $20 million processed using its technology every month.

The algorithms underlying Ripple’s technology dictate that there will be no more than 100 billion XRPs to go around. Though the company is giving away many of them to get the system off the ground, it has allocated one-fourth of the hoard to itself and is relying on the XRP’s increasing value as its only source of income. Between the freebies and the ones Ripple has sold to companies and investors who believe the currency will gain value, there are 7.5 billion XRPs in circulation. That’s enough to make Ripple Labs’ cash flow positive—and to show that inventing and selling your own currency really can work.