Danah Boyd

Shaping the rules for social networks.

As more and more people join social-networking sites, Danah Boyd is asking and answering some uncomfortable questions about these online communities. Among other things, she has detailed how race has been a factor in some users’ migration from MySpace to Facebook, how social networks are changing the way teenagers relate to one another, and how the Internet alters the way people think about privacy.

Working as an advisor, Boyd has shaped the policies of companies like Google and LiveJournal. Now employed by Microsoft Research New England, she has been talking with government regulators and privacy advocacy groups to determine how best to help users protect their personal information. She believes that privacy regulation is inevitable and is trying to guide the industry and regulators toward a set of mutually acceptable rules.

Critical to any such solution, Boyd says, is making sure that people can control what happens to their personal data after it has been entered into a social network.

Wesley Chan

Building new technology businesses.

Wesley Chan has a knack for turning good ideas into new businesses–and doing it with minimal resources. In 2005, Chan’s small team at Google, which incorporated two startups he acquired for the company, launched Google Analytics to provide a free version of the tools the search giant previously used internally. In 2006, he dreamed up another free service, Google Voice, which launched in 2009. This one offers automatic transcription of voice mail, the ability to use one number for different phones, and many other features. Given only two company engineers to work with on the project, Chan acquired the startup GrandCentral in 2007; he and his new crew spent the next two years putting the service together in secret.

Google Voice now has millions of users. But Chan has moved on again and is now a partner at Google’s venture capital investment group, Google Ventures. He still invests in software but is free to cast his net wider. In particular, he is developing an interest in stem-cell medicine, even though the field has no direct connection to Google’s business. He says, “For me it’s about going where I can learn the most, and making the output of my learning something that is world-changing.”

Nick Feamster

Watching the suspicious behavior of spam.

For years, e-mail providers, IT departments, and network operators have fought spam with the help of technology that examines what messages say. Nick Feamster, an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, had a better idea. Instead of examining content, he looks at how messages move through networks, on the theory that the traffic flow of legitimate messages and spam should be different.

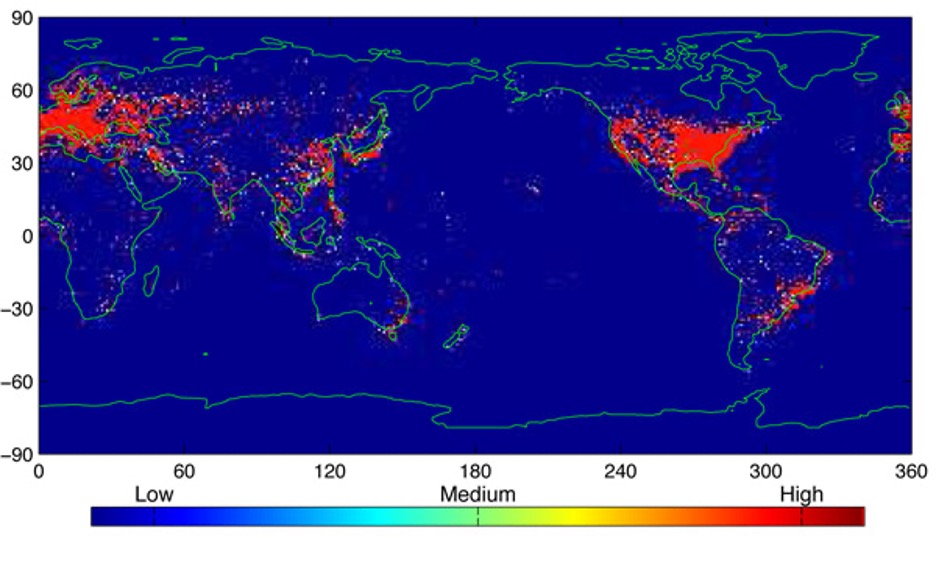

For example, Feamster found that spammers often try to hide in “dark space”–normally unconnected Internet addresses. Suddenly, a previously unreachable block of addresses would light up, send out a bunch of messages, and then disappear. Watching for phantom networks that appear for 10 minutes at a time turned out to be one way to identify and stop spam. His strategies have been adopted by companies such as Yahoo and McAfee in their ongoing struggle to prevent spam from reaching users.

David Karp

A platform that keeps bloggers blogging.

Maintaining a blog takes stamina: of the more than 100 million blogs surveyed by the search engine Technorati in 2008, fewer than 10 percent had been updated in the previous four months. David Karp thought that simplifying posting would stop users from falling away, so he created Tumblr, a streamlined blog platform. The result? Of the site’s six and a half million registered users, 85 percent post more than 20 times a month on average.

Within a few minutes of signing up with Tumblr, users can submit their first post by browser, e-mail, IM, or even voice. And with large buttons dedicated to posting music, video, and photos, it encourages users to go beyond the blocks of text that are the mainstay of typical blogging and social websites. Social-networking features such as following, favoriting, reblogging, and syndication offer ways to give users the positive feedback that keeps them contributing.

Karp launched Tumblr in early 2007. Two weeks later, the site had 75,000 registered users. So far, it has taken in about $10 million in venture funding, but it doesn’t need much. “It’s the most capital-efficient company I’m familiar with,” says Bijan Sabet of Spark Capital.

Lately, Tumblr has been adding 750,000 users a month, prompting Karp to try new ways to bring in revenue. He is charging for promotional spots that let users advertise their blogs and for premium page layouts to make blogs stand out. And if these strategies don’t work? “I can always move back in with my parents,” he says.

David Kobia

Software that helps populations cope with crises.

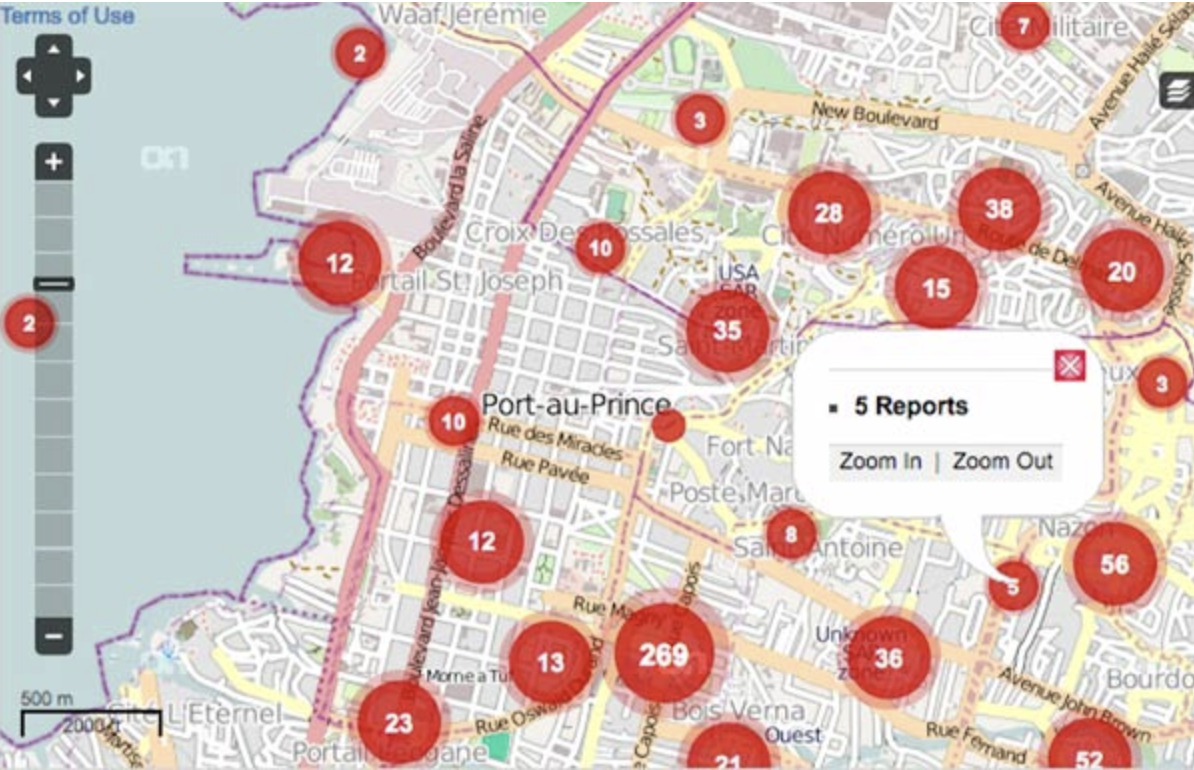

The Ushahidi project brings crowdsourcing to bear on some of the most desperate situations people face around the world. Its downloadable software allows users to submit eyewitness reports during a conflict or disaster; the collected reports are displayed on a map. At times when ordinary sources of news and public information are unavailable, Ushahidi gives users a way to share information and shape political opinion, guide rescuers, or pool resources. Ushahidi has been used to monitor elections in Sudan, document violence in Gaza, track the BP oil slick, and assist earthquake recovery efforts in Haiti.

Ushahidi was born during the riots that followed Kenya’s 2007 presidential election. President Mwai Kibaki had imposed a media blackout throughout the East African nation, so the Internet provided the only open channels of mass communication. David Kobia was 8,000 miles away in Birmingham, AL. A Kenyan expatriate who had dropped out of the University of Alabama at Birmingham to work as a Web developer, Kobia was frantically trying to moderate an online forum, Mashada, that had started as a personal project but was becoming a very public arena for Kenyan politics. Discussions on the site were spiraling into vitriol and paranoia. A French news agency reporting on Mashada called it Kenya’s answer to Radio Mille Collines, the infamous Rwandan radio station that had fueled that country’s genocide in 1994.

“Being mentioned in the same sentence as Radio Mille Collines is akin to being called a Nazi,” says Kobia, a gentle man with an open face and an easy smile. Beset by remorse and despair, he pulled the plug on Mashada, got into his car, and sped up Interstate 20, planning to spend a somber winter holiday with friends in Atlanta. Somewhere near the Georgia border, his cell phone rang. An online acquaintance, Erik Hersman, was calling. Hersman had read a post by a prominent Kenyan blogger, Ory Okolloh, calling for someone with the know-how to program a Google map to track the violence and destruction. “Can you put it together?” Hersman asked. Seeing an opportunity to atone for Mashada, Kobia turned around and headed back to Birmingham. Two days later, Ushahidi was up and running.

Ushahidi map of the disputed Kenyan election in 2007. Credit: Ushahidi

That initial version was simple: just a map and a form that let users describe an incident, select the nearest town, and note the location, date, and time. Nonetheless, it was enough to attract widespread attention. “Suddenly my phone was ringing off the hook to do an interview with BBC News or NPR,” Kobia says.

By now, Ushahidi–the name means “testimony” in Swahili–has played a central role in coördinating the responses to crises around the globe. Kobia, with the help of Hersman, Okolloh, program director Juliana Rotich, and a growing number of coders, has continued to develop and expand the original no-frills online application into a downloadable open-source platform that includes a time line, an API to develop applications for mobile devices, an architecture that allows functionality to be added through software plug-ins, and support for several mapping protocols. It has been used in more than 30 countries, mostly by grassroots relief and watchdog organizations, to direct aid workers to specific locations, document corruption, and track complex events in space and time.

“Ushahidi is one of the most globally significant technology projects,” says Ethan Zuckerman, cofounder of the blog network Global Voices and a senior researcher at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. “It’s built on open standards and accepts input not only from the Web but from mobile devices–a critical feature for enabling global participation. And it evolves with each installation, resulting in a system that can aggregate, map, and authenticate crowdsourced data in a very wide range of environments.”

Redemption

Kobia grew up in Kenya, the son of a civil engineer and a schoolteacher. He moved to America to study computer science at the University of Alabama in 1998. By that time, the dot-com boom was under way, and Kobia left school to build publishing platforms for Time Inc., Reader’s Digest, and Cygnus Publications and also for sites that automated processes such as hiring or booking travel. Through those projects, he gained the deep knowledge of online infrastructure that made it possible for him to assemble the first version of Ushahidi so quickly.

Soon after Ushahidi came online, Kobia was contacted by NetSquared, a nonprofit that promotes the Web as a vehicle for social change. The organizers invited the Ushahidi team to enter its Mashup Challenge, and Kobia flew to San Jose, CA. Walking among the gathered Silicon Valley hipsters, he thought that a group of Africans had little chance. To his great surprise, Ushahidi won the competition. It was a triumphant moment for Kobia, who still felt lingering guilt for the Mashada forum. “I felt drunk with redemption,” he says.

Returning to Birmingham, Kobia wrapped up his business and threw himself into Ushahidi, funded by $25,000 from NetSquared and a grant from Humanity United. Later, he secured some $700,000 from philanthropies including the Cisco, Knight, and MacArthur foundations. The result is a system that packs tremendous communication power into a simple user interface. The platform collects incident reports through e-mail, status updates, and blog posts; reports can include text, photos, audio, and video. It uses another open-source program, FrontlineSMS, to aggregate text messages, making good use of the cell phones that are ubiquitous in the developing world even where computers are rare.

Incoming incident reports queue up on a dashboard screen where administrators–usually volunteers for organizations that have downloaded Ushahidi and set it up on a server–can categorize and vet them by cross-checking against news and other information online. Within minutes of arrival, messages deemed valid are posted to a public Web page, where they appear on a map as colored dots that grow as reports from those locations accumulate.

Helping Haiti

After receiving the NetSquared prize, Ushahidi played a role in crisis after crisis as tech-savvy grassroots organizations downloaded the platform. With each implementation, it grew as users requested features and Kobia and a growing team of developers obliged. The most challenging test came early this year. On the evening of January 12, 2010, Kobia received an urgent phone call from Patrick Meier, director of crisis mapping and strategic partnerships at Ushahidi and founder of the International Network of Crisis Mappers, an Internet-based group that brings together cartographers, imaging experts, and specialists in crisis management. He was looking for ways that digital mapping might help Haiti cope with the aftermath of the earthquake that had just struck.

Kobia set up a Ushahidi website for the crisis, and within hours, the system was fielding reports of human misery on a vast scale–25,000 text messages and 4,500,000 Twitter posts before the month was out. Working through the U.S. State Department, he arranged with Haitian telecommunications companies to supply a four-digit SMS code for emergency messages. Aid workers in Haiti distributed the number on printed flyers.

The bulk of incoming incident reports were written in Creole, so Ushahidi arranged for some 10,000 Haitian expatriates in North America to serve as translators, first through a custom system and later through a partnership with the commercial crowdsourcing website CrowdFlower. Meanwhile, Meier organized Tufts University students to log reports around the clock. First responders, including members of the U.S. military, used Ushahidi’s map to set priorities, organize, and reach distressed people.

Ushahidi had a decisive impact on the Haitian crisis–and vice versa. On the one hand, Kobia was thrilled to see the system rise to the occasion. On the other, the effort almost drove his team into the ground. “We put in 20-hour days for a month,” he says. “Developers were getting burned out.” He realized that the organization was failing in its goal of giving others the ability to use the platform independently.

Since then, Kobia has focused much of his energy on making Ushahidi more accessible and easier to operate. For instance, an initiative called Crowdmap delivers Ushahidi’s functionality directly over the Web, so local groups don’t have to install it on servers of their own. He’s also working on a system that uses machine learning and natural-language processing to evaluate the validity of incoming data.

Some of these efforts might ultimately generate revenue: larger organizations might pay for Crowdmap’s services or license other parts of the Ushahidi technology. This is necessary, Kobia says, to insulate Ushahidi from the whims of charity, about which he is deeply ambivalent. “In truth, I don’t like nonprofits,” he says. “They’ve never solved any problems. Instead, they’ve destroyed free enterprise and turned Africans into beggars. Some of the best programmers in Kenya are working for nonprofits when they could be creating an economy. Ushahidi’s challenge is not to get caught in that cycle.”

To that end, Kobia has started an innovation center meant to galvanize Nairobi’s burgeoning high-tech community. “There’s a pool of mind-blowing talent waiting to be tapped,” he says. “We remind them, ‘It’s your duty to participate in this community and build your own businesses.’ ”

Christopher Kruegel

Developing software that shuts down botnets.

Botnets–armies of enslaved computers that have been infected with carefully crafted worms or viruses–are responsible for more than 80 percent of the over 100 billion spam messages e-mailed daily. Antivirus programs are often ineffective against them, because the software typically works by scanning a computer for signatures of known viruses–and the viruses that turn computers into bots are often too new for these characteristic patterns to have been identified. Christopher Kruegel, a security researcher in the computer science department at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has developed technology that can ferret out an infection even if the virus or worm has no known signature. In 2009, he cofounded a startup called LastLine to commercialize the technology.

It works by detecting when a botnet virus is communicating with its master servers, as it must do to get its commands or to send back data–say, your passwords and credit card numbers. To identify these communications amid legitimate network traffic, Kruegel’s research group analyzed tens of thousands of malware samples per day and teased out the command-and-control messages common to botnets.

Catching these communications makes it possible to block the master servers, forcing criminals to move their infrastructure or redirect their communications. In effect, Kruegel isolates the previously infected computers, neutralizing the infection even if it hasn’t been wiped from your hard drive.

Kati London

Teaching real-world skills through games.

Kati London is blending the virtual and physical worlds to entertain–and to shape the real-life behavior of players. London, a vice president and senior producer at New York-based game company Area/Code, makes games that incorporate real-world data ranging from the mundane (the locations of players) to the exotic (signals from tracking devices attached to sharks in the Pacific). Many of her games are just for fun, but others are more serious.

For example, the U.K.’s Department for Transport commissioned Area/Code to make an online game for children aged 9 to 13, the group most at risk of being killed or seriously injured while crossing the street. When users reach a road in the fantasy-themed game, they can cross at designated safe spots and must look both ways for monsters. The monsters’ behavior reflects that of vehicles; at some crossings, their speed and number is based directly on traffic data from actual intersections in the U.K. By replicating the unpredictable variations in the appearance, speed, and number of vehicles, London believes, the game teaches skills that children need to handle real traffic. More than 160,000 players have been registered since the game was introduced last year, and an independent evaluation is due out next spring.

Avi Muchnick

Cloud-based multimedia editing software.

“Everyone wants to be an artist,” says Avi Muchnick, sitting amid the clutter of his startup’s new Manhattan headquarters. Muchnick’s company, Aviary, makes free Web-based software for creating and editing images and sounds. Users can do everything from tweaking photographs to composing complex multitrack musical arrangements.

Aviary’s tools aren’t as powerful as commercial applications like Adobe Photoshop, an expensive photo editing program that professionals use. But because all user data is stored on a cloud-computing platform, users can easily share not just finished works but all the individual elements that went into a work; if someone creates a graphic of a teacup for a poster about a public reading of Alice in Wonderland, someone else can extract that graphic and use it in a logo for a café. Aviary tracks how and where elements are used, making sure that licenses and credits are preserved. Ultimately, the company hopes to create a marketplace where creators can charge royalties for their work, with Aviary taking a cut. Since the company was founded in 2007, Muchnick has raised $11 million in venture capital and angel funding from investors such as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.