Inside line

MIT’s Dormline—run mainly by students—let generations of students call each other from phones in their rooms.

Before cell phones made telecommunications a back-pocket commodity, the typical US college student had to suffer the indignity of making calls on the hall phone—a communal phone hung in the hallway and often shared by an entire dorm floor. But for decades, MIT students enjoyed the rare luxury of phones in their rooms that could call other dorm rooms; eventually they could direct-dial practically any phone on campus. And in true MIT fashion, this student phone system, known first as “Dorm Phone” and later as “Dormline,” was run and maintained almost entirely by students.

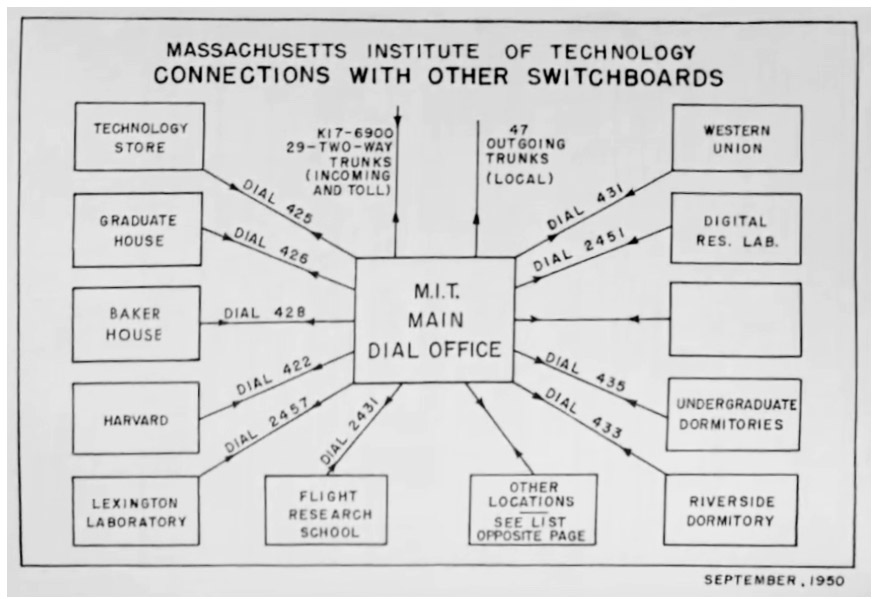

The idea of a phone in every room dates back to the first dorms on campus: 70 Amherst Street (which became Senior House) and East Campus were wired for room telephones when they opened in 1918 and 1924. A switchboard was installed in East Campus in 1930, and 70 Amherst got one a few years later. Likewise, the dorm now known as Fariborz Maseeh Hall, which was built in 1901 as the Riverbank Court Hotel, already had room phones wired to the hotel’s switchboard when it was converted in the late 1930s to a graduate dorm (first called Graduate House and later Ashdown House). In these original dorms, the front desk operator could connect calls between students—and from one dorm to another—by plugging a cable into a socket.

Andrew Stevens ’86, who worked for Dormline from 1983 through 1986, says it was easy to tell that the oldest dorms had been wired for phone service in the first decades of the 1900s because of their vintage cables: twisted copper wires encased in cotton twist fabric insulation.

As early as the 1920s, Professor Carlton Tucker, Class of 1918, began setting up the Institute’s first mechanized phone system for the electrical engineering department in MIT’s main building. This system was based on the Strowger “step-by-step” switch, invented in 1888 by an Indiana undertaker who was convinced that operators were purposely misdirecting his calls and vowed to get even by putting them out of a job. Widely deployed in the US by the 1920s, Strowger switches were being replaced with newer technology by the 1940s, which likely freed up surplus equipment for use at MIT—and for student experimentation. MIT’s Tech Model Railroad Club, for which Tucker was the faculty advisor, also made extensive use of surplus phone equipment.

While Tucker’s phone system was automated, the dorm phones continued to rely entirely on manual switchboards until Baker opened in 1949. The new dorm was wired for phones and got its own step-by-step switchboard, installed by students. As other West Campus dorms were built, they followed suit.

“This is MIT. Collect and third-number calls will not be accepted at this number.”

By the early ’60s, students were essentially running and maintaining the Dorm Phone system and were eager to fully automate it. During the summer of 1963, student workers played a key role in installing step-by-step equipment in the Walker Memorial and Ashdown basements. “Supposedly some of that equipment was manufactured in the 1920s and came from the old John Hancock building,” recalls Stephen Lentz ’86, a Dorm Phone alum. That September, The Tech printed a full-page chart explaining how “any dormitory resident may now place a call to any other resident without the assistance of an operator.”

Calls to the outside world, however, still had to go through dormitory hall phones—and an MIT operator (34 of them were employed in 1969). “Under the present system, an incoming call for a student is connected with the dormitory desk, which calls the student on the dormline,” Olin Reid Ashe Jr. ’70 explained in The Tech in 1969. “When the student answers the dormline, he is informed that he has a call, and told to call the Institute operator on the hall extension. The Institute operator then connects him with his call on the hall extension.”

That all changed in the fall of 1980, when the Dorm Phone crew worked with engineers from MIT Telecommunications and New England Telephone to connect Dorm Phone’s step-by-step system to the Institute’s “Centrex” system, the telephone switch that New England Telephone operated for MIT. Suddenly anyone in the US could directly dial any dorm room by dialing 1-617-225 and the room’s extension—without having to go through an operator. But students still couldn’t make direct outside calls; only collect or credit card calls were allowed, because there was no way to bill dorm residents for individual calls.

This lack of a billing system also presented a problem for incoming operator-assisted calls: operators would have no way of knowing that they were putting through calls to student phones. MIT didn’t want to get stuck with the charges, so Dennis Baron ’72, MIT’s technical manager of telecommunications, who had worked for Dorm Phone as a student, came up with the idea of playing a recording at the start of every incoming call: “This is MIT. Collect and third-number calls will not be accepted at this number.”

“The looped six-second recorded voice announcement was stored on a commercially available solid-state device (the Audichron HQD 220), which also produced an electrical signal at the beginning of each cycle,” says Gregory Stathis ’70, another Dorm Phone alum. “I designed and built the 42 DID [direct inward dial] trunk cards, which interfaced to the announcement machine and connected the voice signal to the caller for one six-second cycle.”

Ironically, the equipment for playing the digitized announcement was “the single most expensive piece of equipment” in the entire system, recalls Stevens. In 1982, the recording was hacked so it played: “This is MIT, where the phrase ‘Sport Death’ has been censored by the Dean’s Office. Collect and third-number calls …”

Baron told The Tech that the total cost of connecting the commercial telephone system and dorm system would be between $20,000 and $30,000, although MIT would save money in the long run because human operators would no longer be needed to complete calls.

For many, the experience of working for Dorm Phone—a paying gig—was career-defining. John McNamara ’64, who would later collaborate with Stevens to create a Dormline history website, got a job at Lincoln Lab as a communications equipment purchasing agent thanks to his experience with Dorm Phone and his personal connection with Professor Tucker (who had remained a Dorm Phone advisor). It was “a nice, stable, draft-free environment,” recalls McNamara, who enjoyed the job and used it to avoid serving in the Vietnam war.

Gary Buchwald ’76, now director of telecommunications at Jewish National Fund, also kicked off his career by working on Dorm Phone. “In every job I’ve ever held since, I’ve also been given the added responsibility of maintaining—and in several cases replacing—the company’s in-house PBX due to my telephony background,” he says. Stathis’s career followed a similar path.

Dormline finally shut down in 1987 when MIT rewired all the phones in student rooms to its new digital system to control costs and take advantage of newer technology. That system remained until MIT removed landlines from student rooms and installed more antennas for improved cell-phone coverage in 2012.

Today some of the last vestiges of Dormline are in the MIT Museum’s collection, which has a step-by-step switch removed from Walker Memorial in 1989, and a circa-1931 telephone with a sticker saying “Inter-Dormitory Calls Only. For Emergency Dial 100.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.