Cold trick indeed

In 1985, students moved a first-year student’s bed onto the frozen Charles River. But the real hack happened in the days that followed.

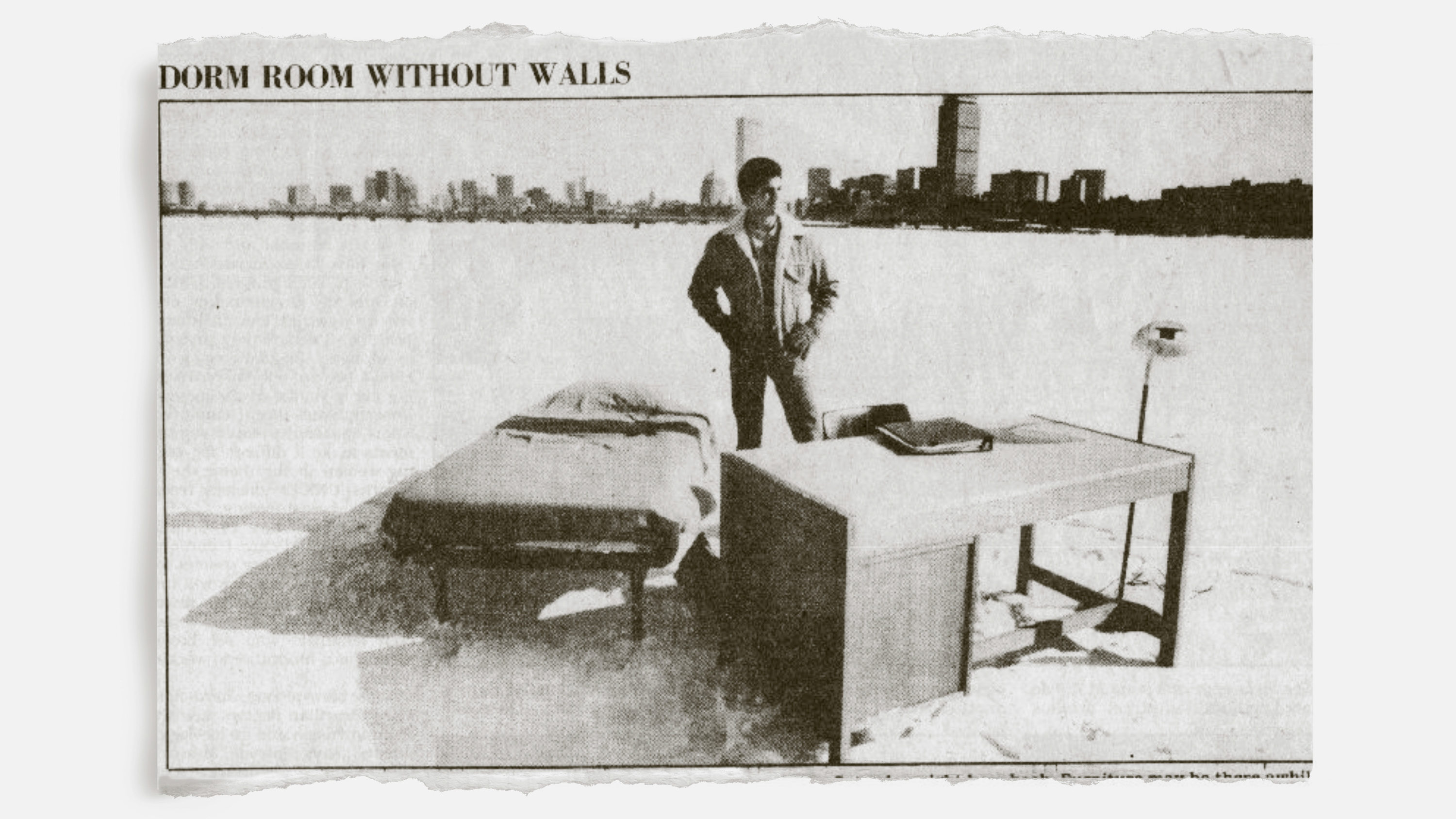

Perhaps it was a slow news day, but more likely it was the amazing photo: MIT freshman Ted Larkin ’88 in jacket and gloves, looking out across the frozen expanse of the Charles River with a broad smile on his face. At his right, a bed, fully made—presumably with those extra-long twin sheets and blankets that MIT students know so well. In front of him, a standard-issue MIT dorm room desk, chair, and floor lamp. On the desk, a binder, most likely filled with problem sets.

“Dorm room without walls,” read the headline that ran on the front page (above the fold) of the Boston Globe on Tuesday, February 5, 1985. “Ted Larkin of New York, an 18-year-old freshman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, stands on frozen Charles River with furniture fellow students removed from his dormitory room while he was at a Saturday night beer bash. Furniture may be there awhile; dormitory manager, deeming ice too dangerous, has refused to let Larkin retrieve his belongings.”

The Associated Press picked up the story, sending a different photo out over the national wire. Versions of how Larkin was pranked by his dormmates appeared in nearly 50 newspapers across the US.

“Students put freshman’s dorm room on ice,” proclaimed the Argus Leader of Sioux Falls, South Dakota. “Dorm room came with a river view” was the headline in the Salina Journal of Salina, Kansas. “Cold trick,” wrote the Sun-Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale, which used the photo to illustrate an article about the record-breaking cold weather that had gripped a third of the US over the previous week (and had left 61 people dead).

The AP also wrote that Larkin had “rounded up a group of friends to help him move everything back,” which clearly wasn’t the case: two weeks after the hack, the furniture was still out there on the Charles.

It was a great story with great photos, but the hack wasn’t on Larkin: it was on the press. The entire thing was staged. It wasn’t even all Larkin’s furniture.

The hack started in the early morning hours following a party hosted by the Burton Third Bombers, the chosen name of the third-floor residents of the Burton side of Burton-Conner, the night before spring registration day. “MIT at the time was supportive of people having a good time without getting too crazy,” recalls David Koch ’86, who was the group’s “floor chair” and the lead prankster.

Larkin’s 18.02 calculus professor started class by holding up the Globe and saying: “I’ve been a professor at MIT for 20 years and I never got my picture in the paper. But one of you freshmen ... What? Is he here? Stand up, you!”

“The river was pretty solid,” he continues, noting that one of the Bombers had crossed the river several times during that year’s Independent Activities Period (IAP) to visit his girlfriend at Boston University. “A group of us—probably only three or four max—said ‘Why don’t we put the bed out on the river?’”

The bed in question was an MIT standard-issue “twin, extra-long” that had indeed been used by Larkin.

“I recently had purchased a waterbed from another student on campus, so I moved my old Burton-Conner dormitory bed into the hallway,” says Larkin, coming clean 37 years after the fact.

So when the party wound down, Koch and a few other Bombers carried the spare bed out to the middle of the river. “We said, ‘You know what, we should set up a whole room out here!’ So we went back and found the rest of the stuff that you see in the picture,” says Koch.

Andrew Ferencz ’87, SM ’89, who was also in on the hack, continues the story: “We called the news to report this, and nobody cared! One of the guys had the idea to say ‘There is a body on the river,’ and right away, they [the media] were excited. But we had to confess: [there was] no body, but there was a bedroom.”

Back in 1985, every MIT student had a rotary “dormline” phone, and Larkin’s started ringing at six the next morning—registration day—with a journalist who wanted to confirm the story. Larkin, who had slept through the whole thing (in his waterbed), had no idea what had happened. He recalls, “I initially responded, ‘Room? River? What?’ but then corrected myself when told by my freshman roommate to ‘say yes to whatever they say!’”

Boston Globe photographer Joe Dennehy showed up, took Larkin out onto the ice, and shot the photo that appeared in the next day’s paper.

When Larkin went to his 18.02 calculus class the morning the photo ran, he recalls, the professor started the class by holding up the Globe and saying: “I’ve been a professor at MIT for 20 years and I never got my picture in the paper. But one of you freshmen ... What? Is he here? Stand up, you!”

For weeks the furniture stayed out on the Charles, thanks to the unusually cold winter. Newspapers around the country kept picking up the photo and running it.

Then, just as the media coverage had dwindled, Steve Liss, a newly hired staff photographer at Time Life, called up Larkin on behalf of People magazine. The next day Larkin, Liss, and Liss’s assistant walked out onto the ice with a box of pizza. “You would be surprised how long the walk is to the middle of the Charles River,” recalls Liss.

Larkin sat at the desk, and Liss started taking photos with his wide-angle lens. Less than a minute later, they heard two helicopters overhead. Police gathered on the bank of the Charles, and two police divers in wet suits with ropes leading back to the shore were making their way out onto the ice. They broke up the photo shoot and threatened to arrest Larkin and Liss, but nothing ever came of it.

Later that day, Koch and a few other students were rounded up by the police and taken out onto the Charles to bring back the furniture. The officers had exposure suits and other safety equipment, recalls Koch, but the students had nothing.

The police impounded the bed, desk, chair, and lamp. (Near the end of the semester, Koch got a call to pick the furniture up, but the chair and lamp were missing.)

People ran the Liss photo the next week—a two-page spread in the February 25 issue—with the headline “If MIT frosh Ted Larkin knows his studies cold, he can credit a textbook case of pranksterism.”

But the real prank had been on the media, which so uncritically accepted the hackers’ story.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.