The engineer who opened doors

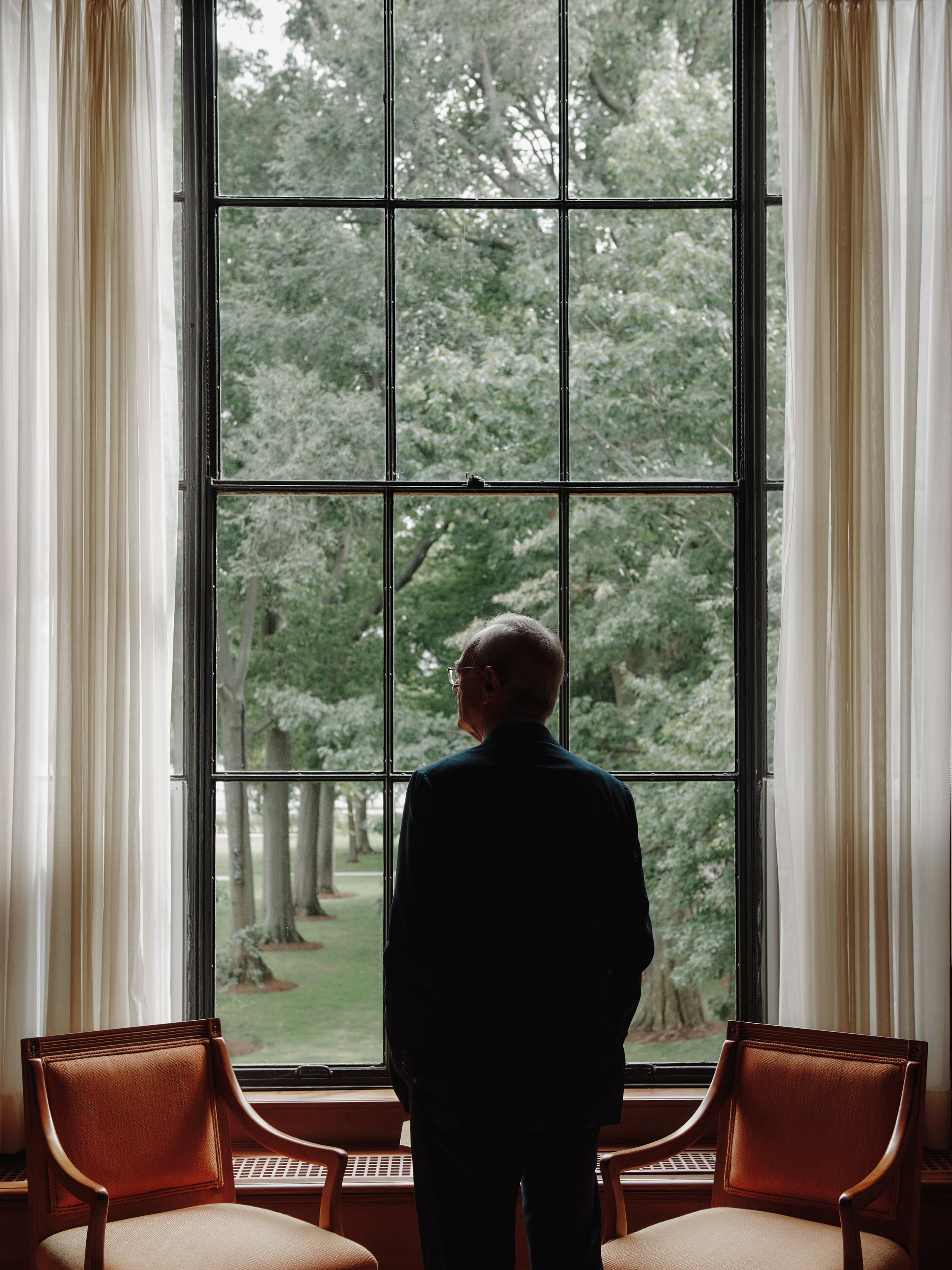

As he steps down, President L. Rafael Reif opens up about the experiences and ideals that shaped his tenure at the helm of the Institute.

In 1952, a pair of MIT faculty members named Arthur Fitzgerald, SM ’31, ScD ’37, and Charles Kingsley published a textbook called Electric Machinery. The book explains the motors and generators that, as they wrote, “provide the power on which industrialized societies depend.” You can still find the first edition in Barker Library, under the dome of MIT’s main building. Over the years, coauthors have added to the volume, whose seventh edition remains in print today.

By the early 1970s, one copy of Electric Machinery had found its way into the library of the Universidad de Carabobo, in Valencia, Venezuela. The college students there generally could not afford to buy textbooks, so some of them shared that library copy. One engineering student in particular regarded the book with awe.

“Going to the library and touching an MIT-authored book—that was like touching the Bible,” says L. Rafael Reif.

Today Reif is MIT’s president, about to step down from the job after more than a decade leading the Institute. Back then, he was a first-generation college student trying to make his education count. Wanting to study something beyond the notes he took in class, he started wrestling with Electric Machinery.

“I could barely understand it,” he says. “I didn’t speak English, but I could read the equations.”

Reif also understood a larger point about the book. The students around him did not know a lot about MIT—they pronounced it “mighty”—but they knew it was special: the kind of institution where the things you read about in textbooks get invented or discovered, and then taught by the people who did the inventing or discovering.

“It was a very important moment to see that there was a place in which what I was studying and struggling to understand—people actually created that kind of knowledge,” Reif says. “I mean, it was almost like seeing, boy, there is a nirvana. There is a place where some people are really dedicated to advancing and spreading knowledge. That was very meaningful to me. It could have been a book from another university, but it happened to be MIT.”

And since Reif happens to be MIT’s president, he enjoys telling people the textbook anecdote, with its layers of meaning. Reif sees MIT as an engine of opportunity—for people on campus, for the students elsewhere who use MIT materials, and for the larger society that may benefit from MIT innovations and ideas. He has been a hard-nosed decision-maker at MIT, an innovator, a prolific fundraiser, and an outspoken commentator on policy issues. But beneath it all is the eager student from South America who knows how much MIT helped him.

“I studied at a university in Venezuela that nobody has ever heard of,” Reif says. “Probably you have no idea where it is—you have never heard of it before. I just came from nowhere.” He continues: “I was very, very fortunate, to come from where I came from and have the opportunity to come to a place like MIT.”

And so, under Reif’s watch, MIT has endeavored to generate more good fortune for more people. It’s conducted a $6.2 billion capital campaign, leveraged a $350 million gift to launch a new college of computing, founded a startup incubator with more than $670 million now under its control, obtained a $100 million gift to launch a new design hub, helped expand Kendall Square as a high-tech center, added new buildings across campus in fields from nanotechnology to theater arts, built dormitories and innovation spaces, and extended the edX platform for online education.

At the same time, Reif has focused on the campus climate. In 2014, he initiated the first study of sexual misconduct at MIT, made the results public, and outlined new steps to combat the problem. He invested in and expanded mental-health resources and backed the founding of MIT’s MindHandHeart coalition to better support the campus community.

And then there are his policy interventions. Reif spoke out strongly against the US government’s travel ban on people from seven largely Muslim countries in 2017; led MIT to file an amicus brief opposing the repeal of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) citizenship program; filed suit with Harvard to let foreign graduate students study remotely during the covid-19 pandemic; and defended an MIT professor who was arrested on charges of failing to disclose ties with China in a government grant application, until the federal government simply dropped the case.

The common thread in all these matters is a desire to forge new opportunities for people to learn, teach, and discover under supportive conditions. Research universities are, to paraphrase Electric Machinery, a source of energy for industrialized societies. The animating concern of Reif’s presidency has been updating MIT to keep it working as such for future generations.

“That drove almost everything I did here: to reach out to many more people like me,” Reif says. “The world is full of people ... who just don’t have the opportunity. It’s as simple as that.”

An immigrant in two places

When Reif was introduced as the Institute’s new president, in 2012, news coverage highlighted his status as the first immigrant to lead MIT, a Venezuelan-born electrical engineer who grew up speaking Spanish. This is true, but Reif’s family history, and its impact on him, is more complicated than that.

Reif’s parents were Ukrainian Jews who fled Europe in the late 1930s amid the growing threat posed by Nazi Germany. The elder Reifs first landed in Ecuador, lived in Colombia for a while, and then moved to Maracaibo, Venezuela (where Rafael was born), and finally Caracas, the capital. Reif’s parents spoke Yiddish and Spanish at home. They had four children, all boys; Rafael was the youngest. Reif’s father did many things to support the family, not always successfully, before settling into photography; his two oldest brothers went to work after elementary school to help out. Over time the family improved its status to “fairly low, low middle class,” as Reif told journalist Karen Arenson ’70 in 2011.

Experiencing the immigrant’s life in both Venezuela and the US shaped Reif’s valuation of opportunity. He says he could sense the “humiliation” his father felt when he was struggling to provide for the rest of the family. “My father was a very smart man,” Reif says. “His life story just didn’t give him the opportunity to study.”

In both Venezuela and the US, education was Reif’s path forward. The second in his family to attend college, after his next-oldest brother, he was interested in many subjects but thought electrical engineering would give him a solid career. And while he’s self-effacing about his college pedigree, a student with the tenacity to grind through a textbook in a nearly unknown language is perhaps a good bet to succeed. Again following in the footsteps of his brother, Reif wanted to attend graduate school in the US.

“I never applied to MIT to come to grad school because I didn’t think they would take a chance on me,” he says. But Stanford did, and he soon found himself in California, learning English in earnest. In 1979 he earned a PhD in electrical engineering, having focused his research on semiconductors.

Reif lined up a job back in Venezuela, but a PhD student he knew from Stanford, Dimitri Antoniadis, had just landed a faculty position at MIT and was aware of another opening at the Institute. Antoniadis (still at MIT today) recommended that he apply. Reif got hired as an assistant professor in 1980 and has been at the Institute ever since.

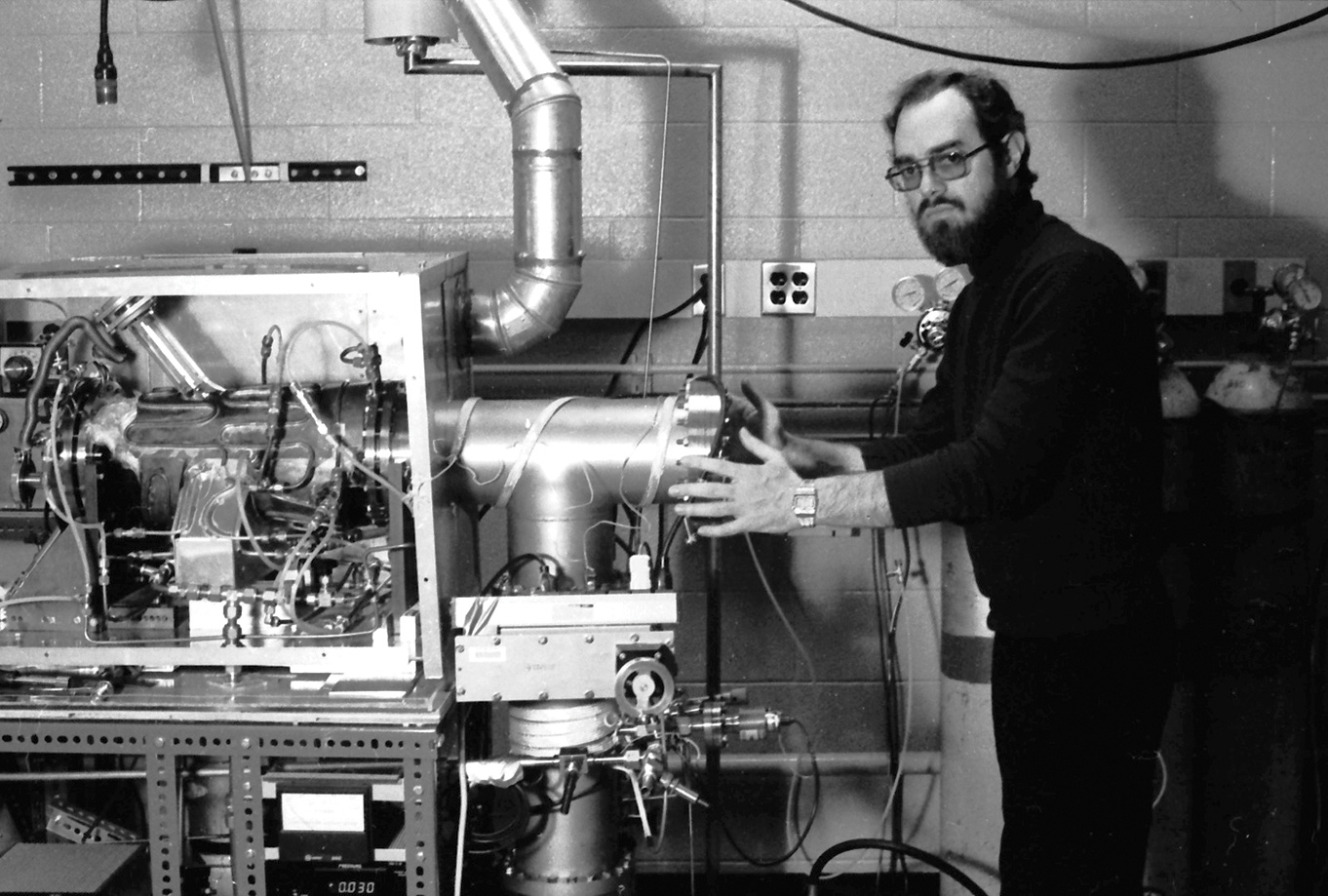

During the 1980s, Reif became a leading expert on the fabrication of semiconductors. His research helped advance methods of depositing often remarkably thin films of material onto silicon wafers, in a process known as heterogeneous integration. He published dozens of papers on the subject and received numerous patents in the field.

“Rafael was one of the earliest people to work in heterogeneous integration,” says Martin Schmidt, SM ’83, PhD ’88, the president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, who served alongside Reif as a faculty member and worked closely with him as MIT’s provost from 2014 to 2022. Such advances, Schmidt adds, helped create ongoing improvements in the processing power of computers: “In a lot of ways, [Reif’s work] was very prescient.”

Reif’s research success also helped spur his career as a campus leader. He served as director of MIT’s Microsystems Technology Laboratories throughout the 1990s. In turn, he became associate head and then head of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. In 2005 he became MIT’s provost—the Institute’s chief academic officer, who oversees faculty issues and many budget matters. By then, Reif had long since become a US citizen and developed a strong attachment to his new nation.

“I have the particular patriotism of an immigrant, rooted in deep gratitude and appreciation for a country founded on a dream of fairness,” Reif wrote in an op-ed in the Boston Globe in 2017.

The relevance of Reif’s immigrant identity to his MIT stewardship is not simply the idea that immigrants can succeed, or that MIT can be a beacon for them. It is more broadly a basic underdog story: If he can get ahead, Reif thinks, other people can too, provided someone gives them a chance.

A worldview, not a checklist

When Reif became MIT’s 17th president, then, he did not have a to-do list so much as a worldview shaped by experience. He may have seemed like a traditional choice—an electrical engineer who’d moved up the MIT organization chart—but that worldview has steered MIT to new places in search of new opportunities.

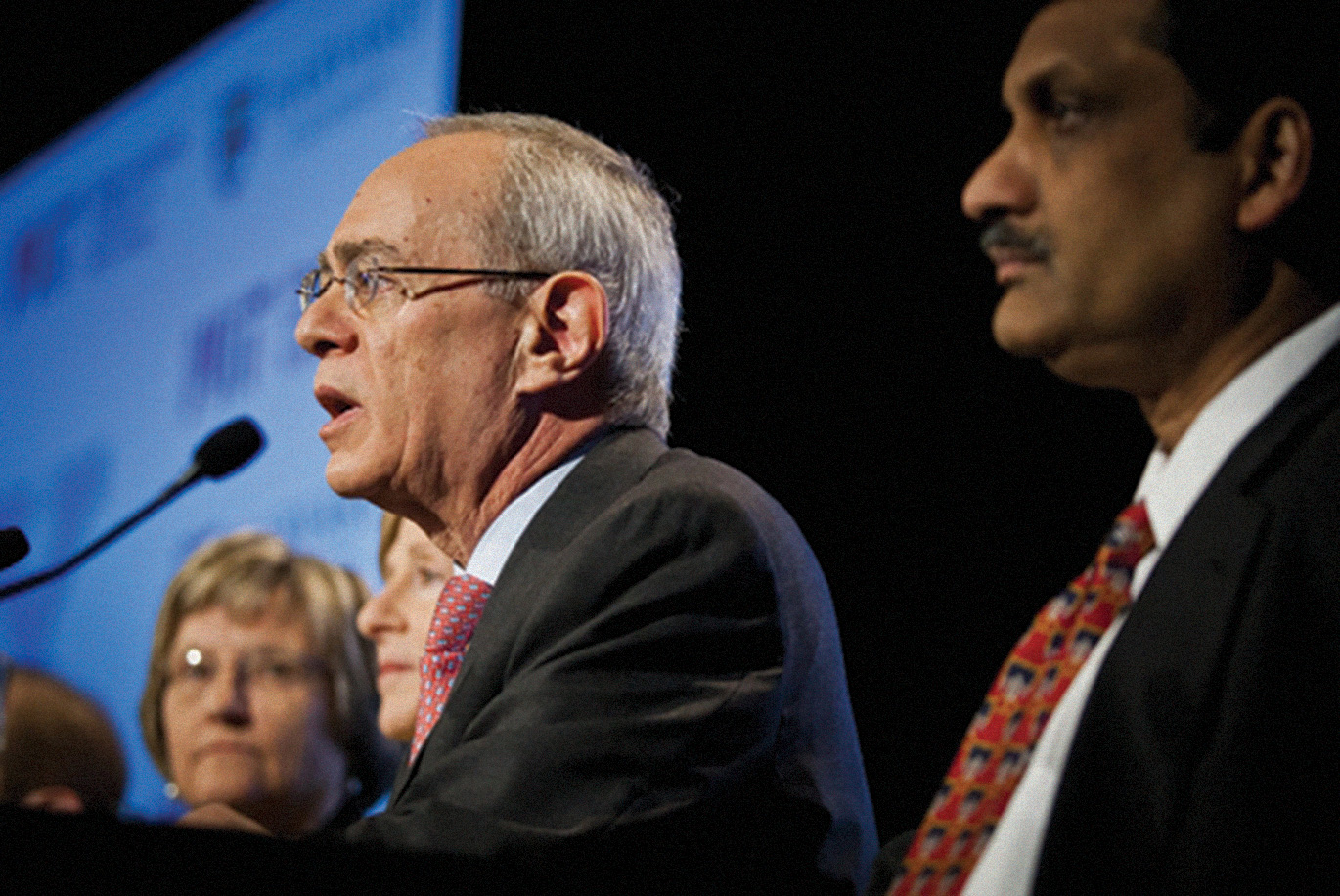

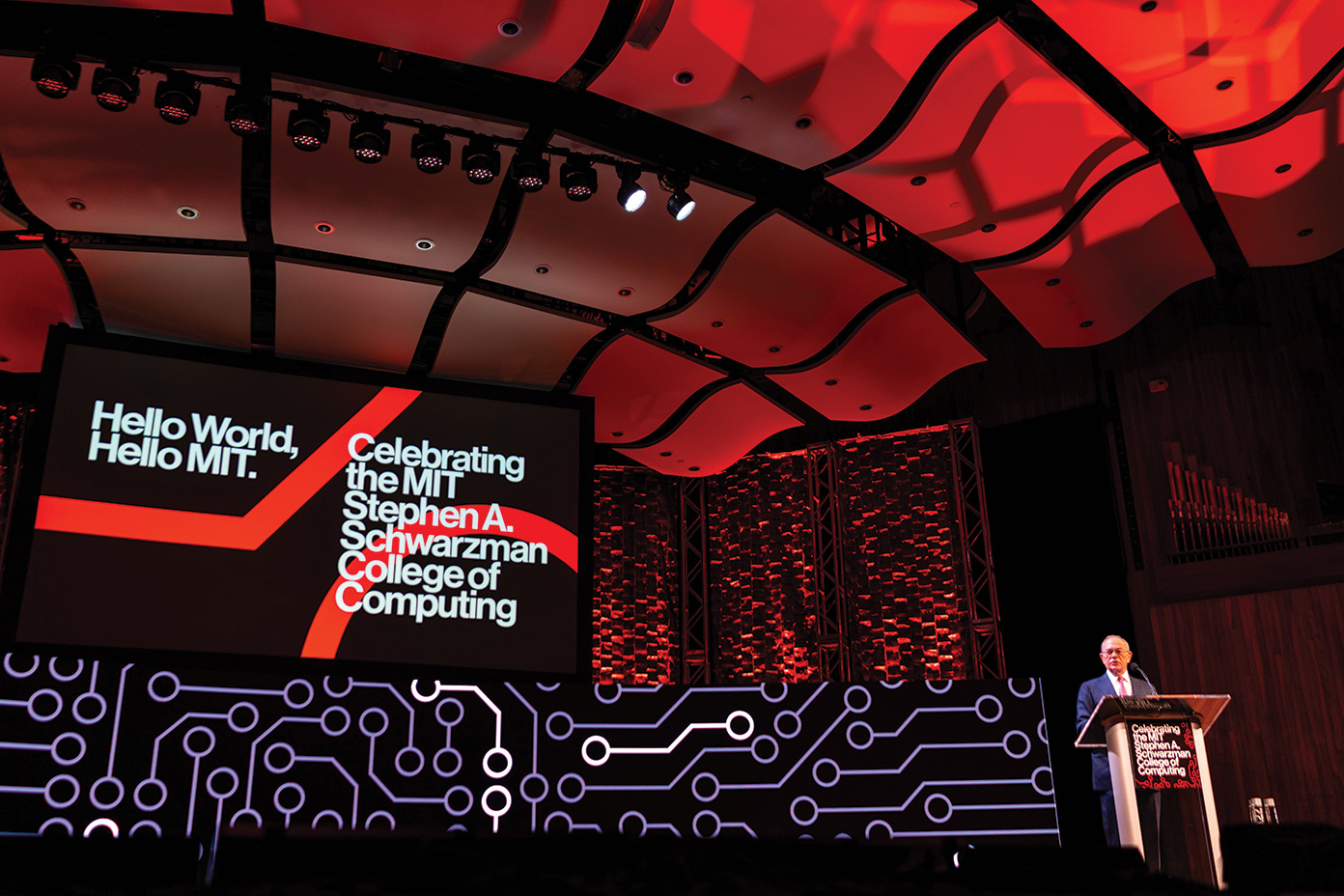

For instance, the creation of the MIT Schwarzman College of Computing—a billion-dollar effort with an emphasis on artificial intelligence, made possible by financier Stephen A. Schwarzman’s $350 million gift—added a college to MIT’s five schools. It was the first change to the formal structure of the Institute in almost 70 years. “The world is becoming much more algorithmic,” Reif says of the new college. As he wrote in a 2019 op-ed, “Students in every field will need to be fluent in AI strategies to advance their own work.”

Or consider The Engine, MIT’s novel venture fund, launched in 2016 and based in Central Square, which specifically backs “tough tech” startups, very often with MIT roots. Because those companies seek to solve hard technological problems, they end up with longer development cycles than the software firms that venture capitalists typically back. They might never get launched without what Reif calls “patient capital.”

“Ideas and innovation were not making it through the system because of this market failure,” he says. “There was no VC money for them.”

In March 2022, MIT also announced a $100 million gift from the Morningside Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the T. H. Chan family, to found the Morningside Academy of Design, a new campus hub linking design research, education, and innovation across all disciplines. “It’s time we introduced design thinking into everything we do,” Reif says.

Such projects, including the opening of MIT.nano in 2018, “are to me critical building blocks of what the future has for us,” he adds, “and I think MIT is very well positioned to move in any direction, partly thanks to those opportunities.”

But when Reif talks about the “pillars” MIT has built in the last decade, programs and buildings are just part of the list. He is equally quick to cite the 2014 effort to investigate sexual misconduct on campus as a crucial step forward for the Institute. Working with then-chancellor Cynthia Barnhart, SM ’86, PhD ’88, who is now MIT’s provost, Reif launched one of the first university surveys about sexual misconduct; then MIT became the first high-profile university to make its results public.

Barnhart led follow-up efforts to better inform students about reporting options and support resources. She founded the Institute Discrimination and Harassment Response Office and increased staff support for violence prevention and counseling. “This derived from a deeply held belief Rafael has that the members of our community must be safe,” Barnhart says.

“I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say that President Reif’s leadership, his care, and his empathy helped to give us the language that we needed to talk about … student sexual misconduct and mental health,” says current MIT chancellor Melissa Nobles. “He and his leadership team at the time, including Chancellor Barnhart, engaged the community in the hard work of facing the hard facts so that we could understand the problems and work through them, and come up with meaningful solutions.”

Back in 2012, no one could have foreseen Reif’s outspoken advocacy on immigration and foreign student policies, either. While the travel ban was upheld by the US Supreme Court, MIT’s efforts to let foreign graduate students study remotely, if needed, helped lead the government to drop a proposed policy that would have prevented them from doing so.

“College presidents had, and perhaps still do, the reputation that all they do is ask you for money,” Reif says. “That’s the job. You’re a fundraiser.” He continues: “Once I realized people view college presidents like that, I said, ‘Wait a minute, we have a little more to offer here’ … Sometimes we may be able to offer opinions that matter.”

Becoming a forceful voice on such topics as immigration policy “was very gradual” for Reif. “I don’t even know that I can go as far as to say it was my responsibility as president,” he says. “But I just felt that I have to speak up because, if I didn’t speak up, who would?”

That attitude is characteristic of him, Reif’s colleagues say.

“I think Rafael’s approach to these complicated challenges in international issues reflects his personal qualities and his humanity,” says Richard Lester, a professor of nuclear science and engineering and MIT’s associate provost for international activities. “He has found ways to connect his own human relations with individuals and members of our community to his larger views on international relations and MIT’s role in them. I think for Rafael these are not only abstract issues. They’re also personal issues.”

The elements of a style

Many of those who have worked closely with Reif suggest that related elements define his leadership style. Barnhart lists three. One, she says, “is his belief in the power of access to education, for individuals and for society.” Another is Reif’s “respect for and empathy toward people, the people of MIT, and his deep appreciation for community.” A third, she says, is that he likes “bold” actions.

“I think the trademark of Rafael is that he combines those things as he thinks about what it is he’s going to do,” Barnhart says. “They don’t work in isolation.”

Certainly Reif’s long-standing support of online education—including the expansion of the edX platform cofounded with Harvard under his predecessor, Susan Hockfield—combines his interest in access to education, his willingness to experiment, and his global outlook. EdX was recently sold to become a public benefit subsidiary of 2U Inc., but MIT has developed MicroMasters programs that blend online and on-campus instruction, and its deep experience with online learning simplified the pivot to remote classes early in the covid-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, Reif has made a practice of seeking input from others, through an array of MIT task forces and working groups charged with studying issues, gathering data, and making recommendations. Schmidt describes his style as being highly “consultative” in this way.

Schmidt notes that when some students who had provided input to MIT during the presidential search offered to serve as a transition team for Reif, he not only took them up on the offer but turned the group into a student advisory council that regularly met with him throughout his presidency. “I think Rafael welcomed that,” Schmidt says.

“He views the MIT community as essential drivers in the direction that MIT will go,” Barnhart says. “If he has an idea, he will always go to the faculty, go to the students. He has a student advisory committee; he has a mode of operation very much geared toward hearing from the community.”

Moreover, Barnhart adds, Reif tends to think that his own initial ideas can be improved by others, whether they’re task force members or simply members of the MIT community. “Ultimately what is created could be looking somewhat different from the initial thought,” Barnhart says. “But that would be, in Rafael’s mind, success. The people of MIT are the ones who make MIT.”

Nobles, who first encountered Reif when he was provost, remembers discovering that he wanted to discuss world events and issues related to her field, political science, and think about how they might bear on MIT. “I’ve always thought of his vision as global, because it was attempting to take in as much as possible,” she says. “And combined with that … you can trust him to be future-thinking, future-looking, very much in keeping with MIT. I think it’s just in his nature to think about things in that way.”

More recently, as dean of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Nobles watched Reif persistently work to develop a new music building—just one part of a wider effort to enhance the entire campus. Today the structure is rising near Kresge Auditorium. “It wasn’t just the building—it was the importance and recognition of what art and culture mean to societies, and most especially to our students,” Nobles says.

Under Reif, MIT also made addressing climate change a priority, launching the Climate Grand Challenges initiative and implementing campus emissions reduction programs. And MIT Solve, an innovation marketplace that tackles global problems by funding entrepreneurs from around the world, was Reif’s brainchild. Started in 2015, Solve gives previously overlooked ideas and projects a chance to come to life.

At the same time, Reif continued to champion projects initiated during Hockfield’s tenure, including the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership, a collaboration with the federal government to create jobs, train workers, and make the US more competitive in emerging areas of industry.

Letters from Gray House

In the future, the full record of the Reif presidency will draw heavily on the many letters to the MIT community he issued at difficult moments such as the 2013 on-campus murder of MIT police officer Sean Collier in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing. Reif helped lead his memorial service and worked to ensure that he would be remembered. MIT built the remarkable Collier Memorial designed by J. Meejin Yoon, then a member of the faculty; one of Collier’s brothers worked on the sculpture’s construction.

“I remember everybody saying [MIT] was … just a place for very tough people—you sink or swim,” Reif says, but “I just felt MIT really was much more than that.”

Not everything at MIT has unfolded as Reif expected. In 2018, after the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the Institute encountered criticism for having pursued educational and research collaborations with Saudi Arabia. But after a review led by Lester, the associate provost for international activities, and despite student calls to end its relationship with the country, MIT elected to continue programs including the Ibn Khaldun Fellowship for Saudi Arabian Women, which brings women with PhDs to the Institute. While saying he had “great respect” for those opposing his position, Reif wrote that he believed “building knowledge and helping more people gain access to higher education constitute the surest path to social progress” in Saudi Arabia.

In 2019, news broke that convicted sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein had donated money to the MIT Media Lab and to fund research by a professor of mechanical engineering. In response, Reif and the MIT Corporation’s executive committee authorized MIT’s general counsel to hire a law firm to conduct a fact-finding review, which determined that Reif had had no knowledge of the situation. He had signed a 2012 donor thank-you note to Epstein, one of hundreds sent out that year, without knowing who Epstein was. MIT subsequently made substantial donations to four nonprofit organizations aiding victims of sexual abuse, while the Media Lab parted ways with its director, Joi Ito, and made changes to its governing structure. MIT also responded to the Epstein situation by having two faculty-driven committees begin to revamp guidelines around gifts, grants, and outside engagements. Reif prefers to learn from problems, not dwell on them. MIT is at its best, he says, “when it is strategic and looks into the future.”

In another unexpected though entirely different situation, Gang Chen, an MIT professor of mechanical engineering, was detained at Boston’s Logan Airport in early 2020 and then charged in January 2021 on allegations of federal grant fraud as part of the US government’s China Initiative, intended to crack down on economic espionage and trade-secret theft. MIT quickly provided Chen with more legal support in 2020, believing he had engaged only in routine academic activities.

“He really paid tremendous attention,” Chen says of Reif. Colleagues also rallied around Chen, publishing an open letter about his case in the MIT Faculty Newsletter upon his arrest. In January 2022, the government finally dropped the case.

“Our defense was never based on any legal technicalities,” said Chen’s lawyer, Robert Fisher, after Chen was cleared. “Gang did not commit any of the offenses he was charged with. Full stop.”

For Chen, Reif’s support was highly significant. “After my case I have talked to many people,” he says. “And everybody admires Rafael, and they admire MIT for standing up for me.” Searching for a word to define Reif’s leadership style, Chen settles on “compassionate” above all. “You really see it supporting faculty, supporting students,” he says. “A passion for people.”

Asked how much his experience has informed his actions, Reif seems more willing than ever to acknowledge that his own life has shaped his work as president.

“It’s personal—it’s just personal,” he says of his interest in speaking out on behalf of students and faculty, and sending out his letters to the community. Of course, it’s not only personal—and, as Lester observes, it’s not only abstract. Reif has calculated what kinds of academic investments MIT needs while bringing his own moral sensibility to bear on many issues.

More than anything, from 2012 to 2022, Reif has consistently bet on the idea that there are many other eager students out there who can lift themselves up while benefiting society. There may even be, in 2022, a student from a refugee family poring over an MIT-authored textbook in a library somewhere, hoping that a better education will lead to a new life.

“I ended up being here, and I wanted, I wanted so strongly—and I hope I made a difference there—to reach out to so many people like me who didn’t have the chance and opportunity that I had,” Reif says. “That was my driving force, always.”

The Reif decade:

A timeline of quotes from L. Rafael Reif

“I grew up in a home wealthy in integrity and principles and values, but poor in everything material … A few decades later I am standing here in front of you, ready, eager, excited, and inspired to lead one of the most remarkable academic institutions in the world.”

Remarks upon being named MIT’s 17th president, 5/16/12

“The research university is not an ornament or a luxury that society can choose to go without. The research university may be the most powerful source of leaders, ideas, and economic growth that the world has ever known.”

Inaugural address, 9/21/12

“The world knows that Officer Collier was killed in the line of duty. But he had a deep, broad, beautiful sense of what his duty involved. He made countless friends on our campus … Officer Collier did not just have a job at MIT—he had a life here … He was truly one of us.”

Remarks at campus memorial service for Sean Collier, 4/24/13

“As you go out into society, I want you to change the source code. Rewire the circuits. Rearrange the molecules. Reformulate the equation. In short, I want you to hack the world … until you make the world a little more like MIT. More daring and more passionate. More rigorous, inventive, and ambitious. More humble, more respectful, more generous, and more kind.”

Charge to the Class of 2013 at commencement, 6/7/13

“I am convinced that digital learning is the most important innovation in education since the printing press … it is surely not very good at replacing a close personal connection with an inspiring teacher and mentor. However, it is incomparably good at opening possibilities for billions of human beings who have little or no other access to higher learning.”

Time Magazine op-ed, 9/26/13

“[The US innovation] system leaves a category of innovation stranded: new ideas based on new science … The result? As a nation, we leave a lot of innovation ketchup in the bottle.”

Washington Post op-ed, 5/22/15

“[The LIGO] discovery embodies the paradox of fundamental science: that it is painstaking, rigorous, and slow—and electrifying, revolutionary, and catalytic. Without basic science, our best guess never gets any better, and ‘innovation’ is tinkering around the edges.”

Boston Globe op-ed, 2/12/16

“MIT has been, from its very beginning, a magnificent human machine for inventing the future … In a sense, MIT’s greatest invention may be MIT itself … an unusual concentration of unusual talent, forever reinventing itself on a mission to make a better world.”

Remarks at Better World campaign launch, 5/6/16

“When it comes to the most important problems humanity needs to solve—climate change, clean energy … and infectious disease, to name a few—there is no app for that … The Engine will help deliver important answers for addressing such intractable problems—answers that might otherwise never leave the lab.”

Boston Globe Op-Ed, 10/26/16

“At MIT, when our community is at its best, bigotry and discrimination are out of bounds, period … Such behavior is simply beneath us—because we value each other as members of our community and respect each other as fellow human beings.”

Letter to the MIT community, 12/21/16

“The Executive Order on Friday appeared to me a stunning violation of our deepest American values, the values of a nation of immigrants: fairness, equality, openness, generosity, courage … If we accept this injustice, where will it end? Which group will be singled out for suspicion tomorrow?”

Letter to MIT in response to travel ban, 1/30/17

“America’s strength in science and engineering is central to America’s strength, period. It’s how we keep the nation safe, drive innovation, build infrastructure, power and connect our modern society, restore the environment, create new industries, feed our people, heal the sick—and understand the universe.”

Letter to the MIT community on proposed federal budget cuts, 3/27/17

“The plight of the [DACA] Dreamers presents a profound question of fairness … They are undocumented through no fault of their own. And when offered an opportunity to come out of the shadows, they did—because they trusted that our government would not punish them for it. Could we ask for more, from any American?”

Boston Globe op-ed, 8/31/17

“Automation will transform our work, our lives, our society. Whether the outcome is inclusive or exclusive, fair or laissez-faire, is up to us. Getting this right is among the most important and inspiring challenges of our time … Technologies embody the values of those who make them. It is up to those of us advancing new technologies to help make certain that they do not wind up damaging the society we intend them to serve.”

Boston Globe op-ed, 11/10/17

“The most important work is up to all of us. We need to actively build a culture that treats sexual harassment, coercion, and assault as taboo, absurdly out of bounds—unthinkable for anyone, of any age, in any context.”

Letter to the MIT community, 11/29/17

“If all we do in response to China’s ambition is to try to double-lock all our doors, I believe we will lock ourselves into mediocrity.”

New York Times op-ed, 8/8/18

“MIT moves forward like science itself: We make new ways of seeing—and then we see new ways of making … That self-reinforcing cycle is the essential vision behind MIT.nano.”

Remarks at the grand opening of MIT.nano, 10/4/18

“I begin with congratulations—because I have reason to believe that no one may have ever been better prepared than Larry Bacow to lead this extraordinary institution. I say that because, at MIT, we have spent decades getting Larry ready to take this job … So as you can see, the best MIT hacks take time!”

Remarks at inauguration of Bacow as Harvard’s president, 10/5/18

“To prepare society for the demands of the future, institutions must equip tomorrow’s leaders to be ‘AI bilingual’ ... We must all be alert to the risks posed by AI, but ... nations and institutions which act now to help shape the future of AI will help shape the future for us all.”

Financial Times op-ed, 2/10/19

“The hidden strength of a university is that every fall, it is refreshed by a new tide of students … Part of the genius of America is that it is continually refreshed by immigration—by the passionate energy, audacity, ingenuity, and drive of people hungry for a better life.”

Letter to MIT on rise in anti-Asian sentiment, 6/25/19

“Our international students now have many questions—about their visas, their health, their families, and their ability to continue working toward an MIT degree. Unspoken, but unmistakable, is one more question: Am I welcome? At MIT, the answer, unequivocally, is yes.”

Letter to MIT on change to F-1 visa policy, 7/8/20

“Why is foreign talent so important to the United States? For the same reason the Boston Red Sox don’t limit themselves to players born in Boston: The larger the pool you draw from, the larger the supply of exceptional talent. Moreover, America gains immense creative advantage by educating top domestic students alongside top international students. By challenging, inspiring, and stretching one another, they make one another better, just as star players raise a whole team’s level of play.”

New York Times op-ed, 7/14/20

“Twice a year, in November and January, the sun lines up with the Infinite Corridor to produce the dazzling effect we call MIThenge. This year … it looks like a light at the end of the tunnel. Thanks to multiple extraordinary triumphs of biomedical research, some very close to home, there is reason to hope that the pandemic’s days are numbered.”

Letter to MIT, 11/24/20

“Humanity must find affordable, equitable ways to bring every sector of the global economy to net-zero carbon emissions no later than 2050. At the same time … we must adapt to effects of climate change we can’t prevent … at fast-forward speed.”

Letter to MIT on Fast Forward climate plan, 5/12/21

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.