Scar-resistant implants

A soft, inflatable device could be the key to developing an artificial pancreas.

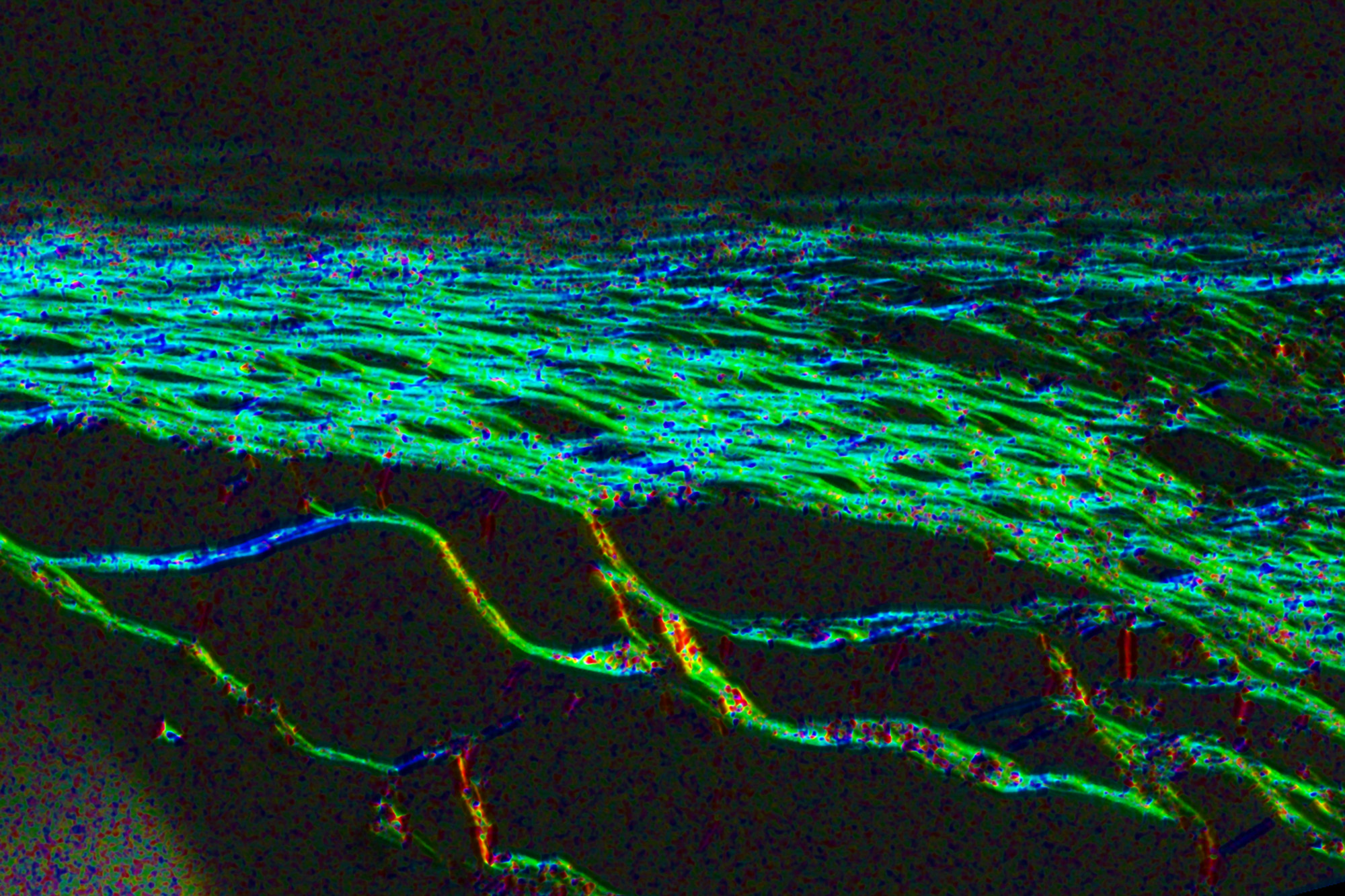

One obstacle to using implantable devices for delivering drugs such as insulin is that the immune system attacks the implant, forming a thick layer of scar tissue that blocks the drugs’ release. Now MIT engineers and collaborators have devised a way to overcome this response without any immunosuppressant drugs.

The team incorporated a drug reservoir into a soft robotic device that also includes a mechanical actuator, which repeatedly inflates and deflates the device. This action drives away immune cells called neutrophils, which initiate the process that leads to scar formation. Any scar tissue that does develop takes a form more likely to let drugs through. In mice, they showed that the device remained functional for much longer than a typical drug-delivery implant.

“We’re using this type of motion to extend the lifetime and the efficacy of these implanted reservoirs that can deliver drugs like insulin, and we think this platform can be extended beyond this application,” says Ellen Roche, senior author of the study along with her former postdoc Eimer Dolan, now a faculty member at the National University of Ireland at Galway.

The researchers now plan to see if they can use the technology to deliver pancreatic islet cells to people with diabetes, forming a “bioartificial pancreas.” Other possible applications include delivering immunotherapy to treat ovarian cancer and drugs to prevent heart failure in patients who have had heart attacks.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.