Smoking gun

Study finds chemical link between wildfires and ozone depletion.

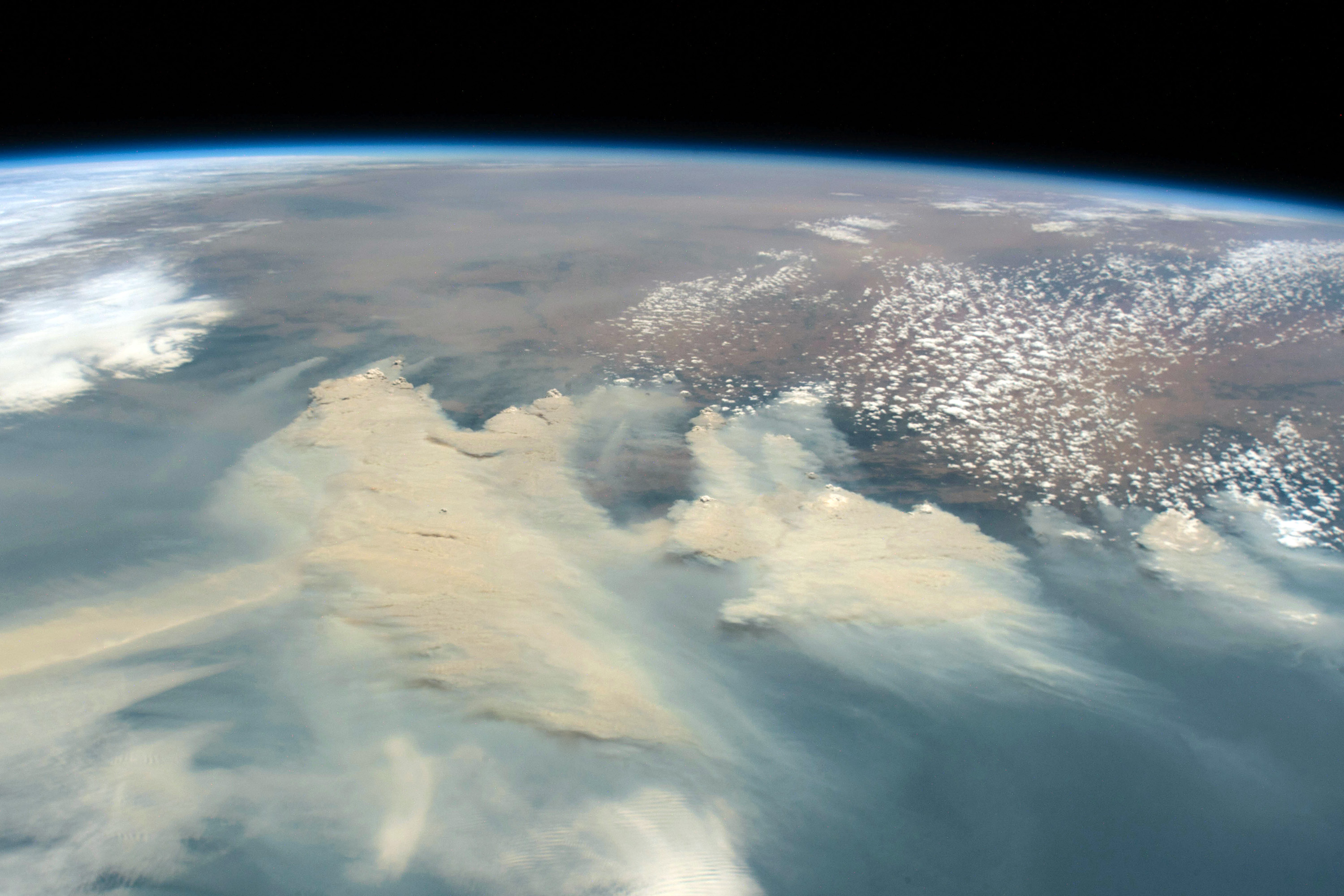

In 2019 and 2020 wildfires blazed across more than 43 million acres of Australia, injecting over 1 million tons of smoke particles into the atmosphere. Now, atmospheric chemists at MIT have found that the smoke from those fires set off chemical reactions in the stratosphere that contributed to the destruction of ozone, which shields the Earth from incoming ultraviolet radiation.

A team led by environmental studies professor Susan Solomon showed that in March 2020, shortly after the fires subsided, nitrogen dioxide in the stratosphere dropped sharply, which is the first step in a chemical cascade known to end in ozone depletion. The researchers found that this drop in nitrogen dioxide directly correlates with the amount of smoke that the fires released into the stratosphere. They estimate that this smoke-induced chemistry depleted the column of ozone by 1% for several months, canceling out the roughly 1% ozone recovery from earlier ozone decreases that had been achieved through the phaseout of ozone-depleting gases.

“As the world continues to warm, there is every reason to think these fires will become more frequent and more intense,” says Solomon. “It’s another wakeup call, just as the Antarctic ozone hole was.”

Massive wildfires are known to generate pyrocumulonimbus—towering clouds of smoke that can reach into the stratosphere (15 to 50 kilometers above Earth). Solomon wondered whether smoke from the Australian fires, which went as high as 35 kilometers, could have depleted ozone through a chemistry similar to volcanic aerosols. Major volcanic eruptions can also reach into the stratosphere, and in 1989, Solomon discovered that the particles in these eruptions can destroy ozone through a series of chemical reactions. As the particles form in the atmosphere, they gather moisture on their surfaces. Once wet, the particles can react with circulating chemicals in the stratosphere, including dinitrogen pentoxide, which reacts with the particles to form nitric acid.

Normally, dinitrogen pentoxidereacts with the sun to form various nitrogen species, including nitrogen dioxide, a compound that binds with chlorine-

containing chemicals in the stratosphere. When volcanic smoke converts dinitrogen pentoxide into nitric acid, nitrogen dioxide drops, and the chlorine compounds take another path, morphing into chlorine monoxide, which destroys ozone. “This chemistry, once you get past that point, is well established,” Solomon says. “Once you have less nitrogen dioxide, you have to have more chlorine monoxide, and that will deplete ozone.”

Studying the Australian fires’ impact, Solomon’s team found that observations of nitrogen dioxide taken by three independent satellites surveying the southern hemisphere all showed a significant drop in nitrogen dioxide in March 2020. To check that the nitrogen dioxide decrease was a direct chemical effect of the fires’ smoke, the researchers carried out atmospheric simulations using a global, 3D model that simulates hundreds of chemical reactions in the atmosphere, from the surface through the stratosphere. They injected a cloud of smoke particles into the model, simulating what was observed from the Australian wildfires, and found that as the amount of smoke particles increased in the stratosphere, concentrations of nitrogen dioxide decreased, matching the observations of the three satellites.

“It’s the first time that science has established a chemical mechanism linking wildfire smoke to ozone depletion,” says Solomon. “It may only be one chemical mechanism among several, but it’s clearly there.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.