A better way to clean solar panels

New waterless method cleans dust from solar installations in the desert.

Solar power is expected to account for 10% of global power generation by 2030, and much of that power is likely to be harvested in desert areas, where sunlight is abundant. But the accumulation of dust on solar panels or mirrors can reduce the output of photovoltaic panels by as much as 30% in just one month.

The regular cleaning that solar panels require currently is estimated to use about 10 billion gallons of water per year—enough to supply drinking water for up to 2 million people. Water cleaning also makes up about 10% of the operating costs of solar installations since water typically has to be trucked in from a distance and must be very pure to avoid leaving deposits on the surfaces. But waterless cleaning methods are less effective and labor-intensive and tend to scratch the panels, which also reduces their efficiency.

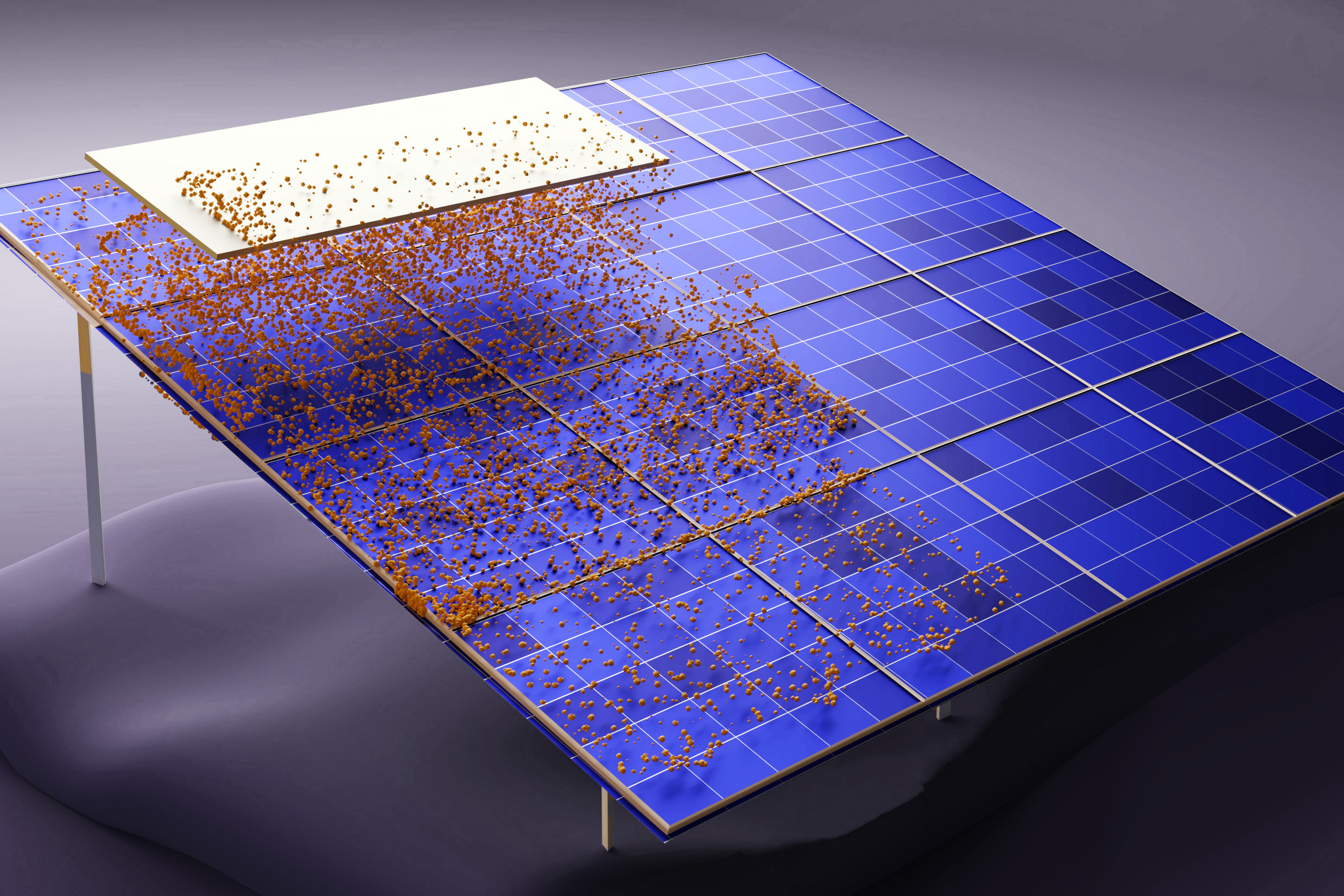

Now, MIT researchers have devised a waterless, no-contact system to automatically clean solar panels or the mirrors of solar thermal plants. The new system uses electrostatic repulsion to cause dust particles to detach from the panel’s surface, without water or brushes. An electrode passes just above the solar panel’s surface, imparting an electrical charge to the dust particles, which are then repelled by a charge applied to the panel itself. The system, which graduate student Sreedath Panat and professor of mechanical engineering Kripa Varanasi described in Science Advances, can be operated automatically using a simple electric motor and guide rails along the side of the panel.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.