Coffee with a college education

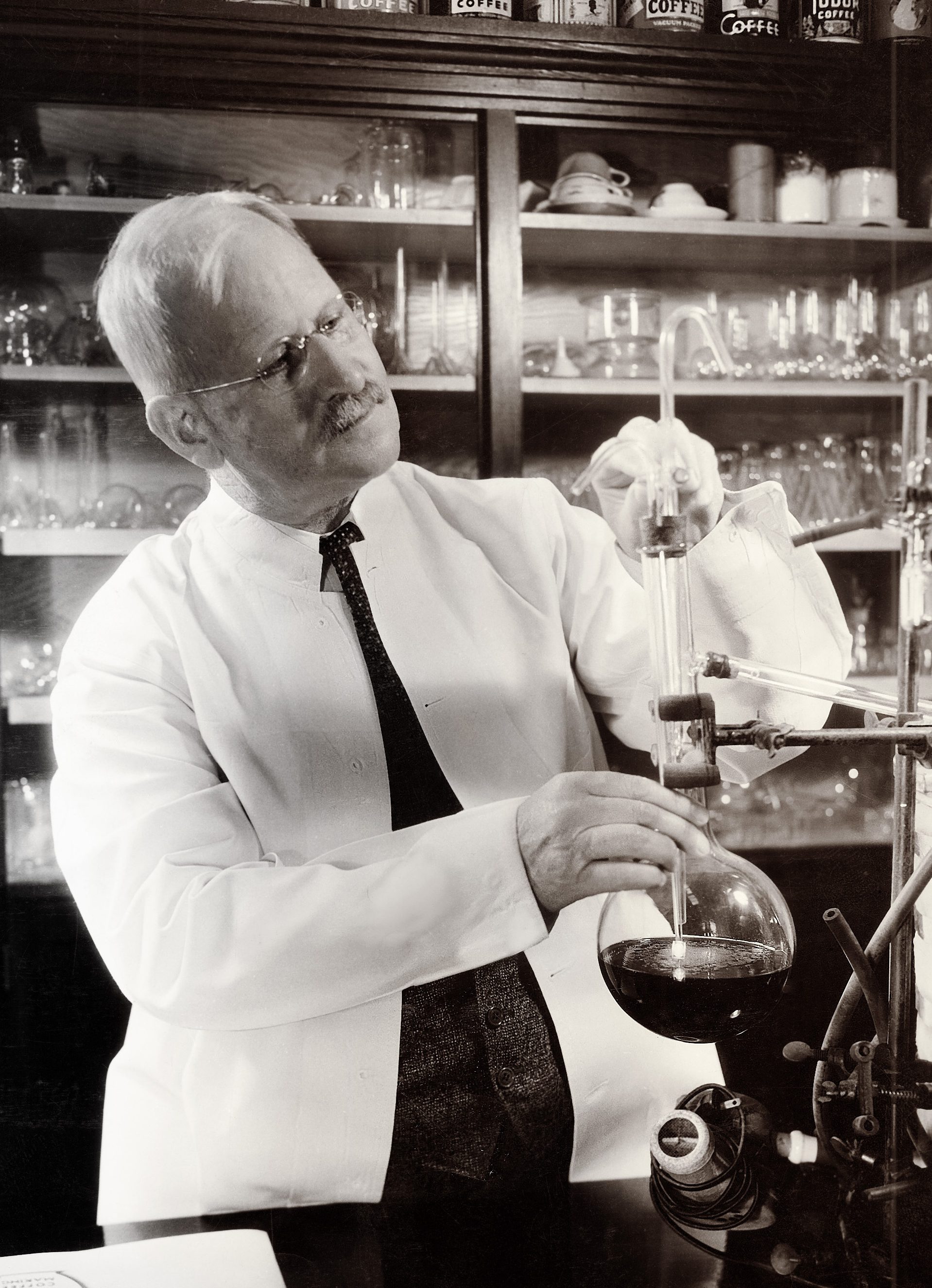

Samuel Cate Prescott used science to build a better cup of joe.

In the early 1920s, Samuel Cate Prescott, SB ’94, spent months wandering through MIT’s hallways, asking one question of any clerks or lab workers who happened to be around: “Do you like coffee?” Most did, so Prescott asked another: “Will you help me in a problem I’ve got?”

Prescott, the head of MIT’s Department of Biology and Public Health, hadn’t tackled a problem like this before. He had graduated from the Institute with a chemistry degree a few decades earlier, returned to the school’s Sanitary Research Laboratory and Sewage Experimentation Station in Boston, and later studied food science just as the Institute’s biology department was pivoting toward using engineering methods to solve problems in health and food quality. Prescott had conducted all sorts of research on food preservation at MIT and while serving in the US Army’s Sanitary Corps during World War I, but now he was facing a more qualitative challenge—how to engineer the perfect cup of coffee.

The project sounded silly and unworthy of an MIT researcher’s time, but there was a lot riding on the outcome. That’s because the domestic coffee industry was struggling.

Coffee consumption in the US had previously grown for decades, largely thanks to cheap prices rooted in exploitive trade agreements and labor practices in Brazil. Bumper crops and overproduction drove coffee down to six cents per pound in 1901. A few years later, however, when the Brazilian government began buying surplus beans to stabilize the market, prices more than doubled. And the price hike dovetailed with a growing sense that coffee was unhealthful. Though most medical experts believed that caffeinated coffee was fine in moderation, research linking the beverage to sleeplessness and nerve disorders gained media attention. One doctor quoted in the New York Times said that selling coffee “ought to be prohibited by law.”

To fight back, the National Coffee Roasters Association formed the Better Coffee Making Committee, which was dedicated to studying coffee scientifically. The committee conducted early studies on the drink’s chemical composition and brewing methods, but the research didn’t reveal a gold standard for retaining coffee’s smell and flavor, or ways to minimize its effects on the nervous system. The roasters needed a well-respected food scientist who could conduct independent studies. In 1920, partnering with the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee, they asked Prescott to create a new laboratory exclusively for coffee research. Some called the project “coffee with a college education.”

The project sounded silly and unworthy of an MIT researcher’s time, but there was a lot riding on the outcome.

Prescott was hesitant. He knew that research on that scale would take at least two years, and he wanted assurance that MIT’s name wouldn’t be used in ad campaigns and that the work would be conducted with integrity and published regardless of the findings. When these concessions were granted, he assembled a research team, including the future Nobel Prize–winning chemist Robert Burns Woodward, and got down to the bitter business of better coffee.

Over the next three years, the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee invested $40,000—over $600,000 in today’s money—in Prescott’s work, which included extensive analyses of coffee’s chemical properties and a review of more than 700 scientific articles and studies. To understand the health effects, Prescott’s team mixed caffeine extract from coffee with water and fed it to rabbits through catheters inserted in their stomachs. They found that caffeine was harmful in large doses: rabbits that ingested at least 242 milligrams per kilogram of their body weight—the equivalent of a roughly 150-pound person drinking 150 to 200 cups of coffee—died. But when the same caffeine amounts were delivered in brewed coffee, some animals survived. When considered in light of the extant scientific literature on the subject, Prescott concluded, these findings suggested it did “not seem probable” that coffee consumed in typical amounts had any acute harmful effects on human metabolism.

Finding the tastiest way to deliver that coffee required more than rabbits. Prescott assembled a “tasting squad”—a group of about 15 women, mostly stenographers and secretaries working at MIT, who gathered every day at lunchtime in the women’s restroom in the Institute’s main building and then walked to a nearby lunchroom, where they waited for someone from Prescott’s team to bring in two chemical flasks filled with coffee and a tray of cups, cream, and sugar. The women, chosen because they weren’t coffee connoisseurs and therefore didn’t have entrenched ideas about the best brewing methods, would sample from each flask. Then they would write down which they preferred and why, never knowing how the coffee had been prepared or what the difference between the two samples was.

This process went on for months as Prescott’s team tested different coffee varieties, brewing methods, grind granularities, and water temperatures and compositions, plus coffeepots made from everything from copper to earthenware. Keenly aware that opinions on this matter were subjective—comparable to soliciting “the quality of a symphony from a group of individuals with different degrees of tone perception and musical taste”—Prescott also recruited many other volunteers. Some were fellow professors, once skeptical of the project, who visited the lab after smelling aromas wafting down the hall.

Prescott’s report was published in 1924, sparking media attention and some criticism. It allayed fears that coffee was harmful—if prepared properly and consumed appropriately, it “gives comfort and inspiration, augments mental and physical activities and may be regarded as the servant rather than the destroyer of civilization,” Prescott said, adding that the beverage relieved fatigue, promoted “heart action,” increased mental concentration, and wasn’t depressive or habit-forming.

The report also contained guidelines for the scientifically proven way to make a delicious cup of joe: use freshly ground coffee—about a tablespoon per cup—and brew in non-alkaline water between 185 and 195 °F for no longer than two minutes. Finer grinds were preferable to coarser ones, and the beverage should be kept in glass, porcelain, or stone pots instead of metallic ones.

The report changed the industry, leading to the development of vacuum-packed coffee and an ad campaign that touted Prescott’s results to 15 million readers nationwide. The ad push, combined with Prohibition in the US, boosted coffee sales and brought a resurgence of coffeehouses throughout the 1920s.

The report was also part of a change happening at MIT. Throughout his tenure at the Department of Biology and Public Health, and later as the first dean of MIT’s School of Science, Prescott funneled more institutional resources into research around improving food quality and cleanliness. He also established a new Department of Food Technology in 1946. Though MIT pivoted away from food and sanitation science after Prescott retired, his legacy remains in the meals on our plates and the drinks in our mugs.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.