The world’s largest collection of malformed brains

The 100 or so jars contain brains that once belonged to patients at the Austin State Hospital, a psychiatric facility.

These cross-sections of a human brain were used for teaching. The collection had been neglected for decades when photographer Adam Voorhes first visited, in 2011. These images are taken from a book he published about the brains, coauthored with Alex Hannaford.

The University of Texas has one of the world’s largest collections of preserved abnormal human brains. The 100 or so jars contain brains that once belonged to patients at the Austin State Hospital, a psychiatric facility. They were amassed over three decades by Coleman de Chenar, the hospital’s resident pathologist, starting in the 1950s.

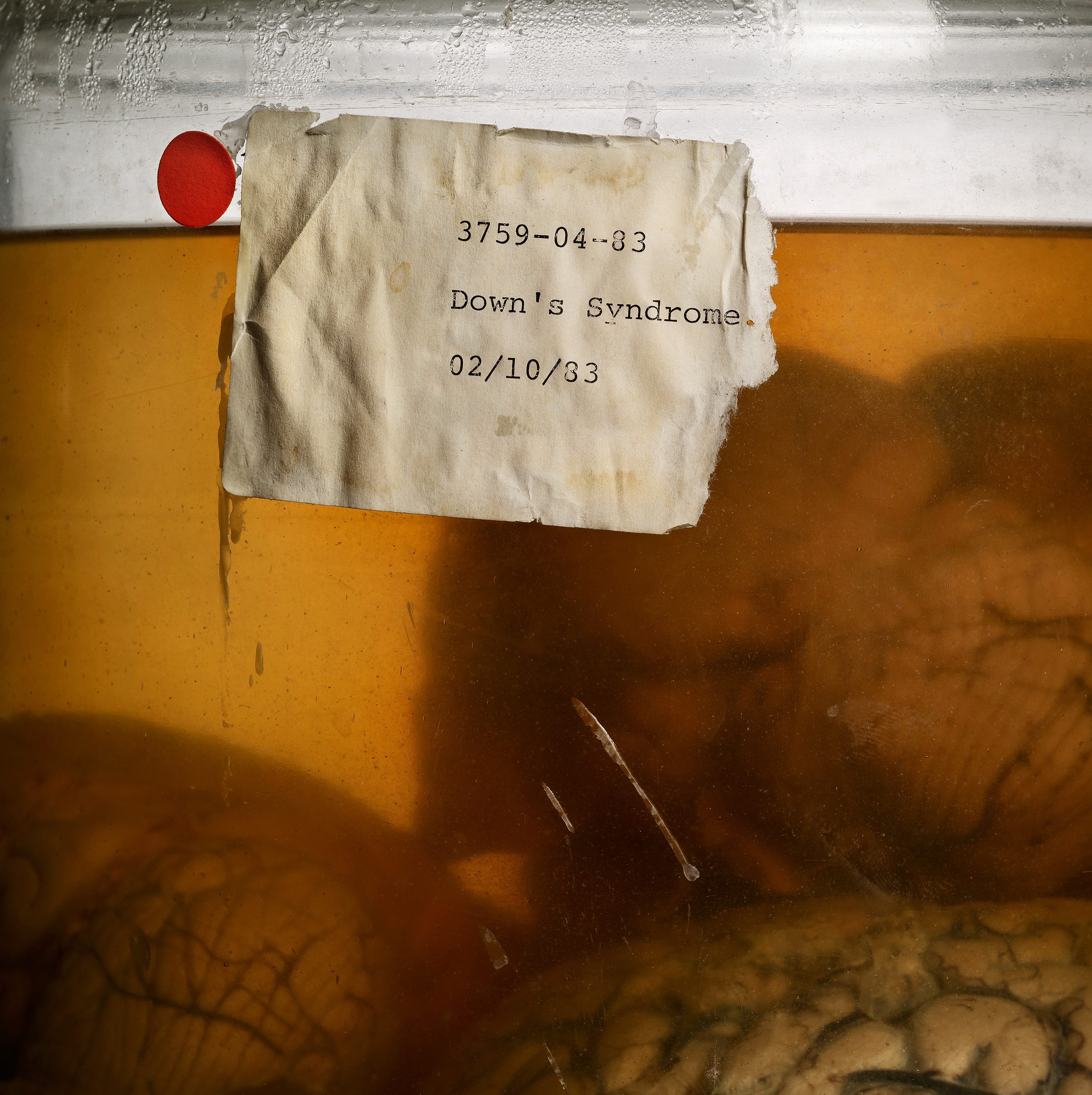

One jar, labeled “Down’s Syndrome” (above), appears to contain more than one brain, and possibly other internal organs. Many jars are missing labels; little is known about the people whose brains these were.

Some abnormalities are obvious, like lissencephaly, or “smooth brain,” a neurological disorder that usually leads to an early death. Many of the brains appear superficially normal but reveal swelling or hemorrhage once dissected. The collection has been scanned by MRI machines.

Correction: The original version of this article named Tim Schallert as the curator for the collection, but he passed away in 2018. The current manager for the collection is Marie Monfils.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.