Chinese astronomers want to build an observatory in the Tibetan Plateau

Most of the world’s most powerful telescopes are in the Western Hemisphere. A new study suggests we start building them in the East.

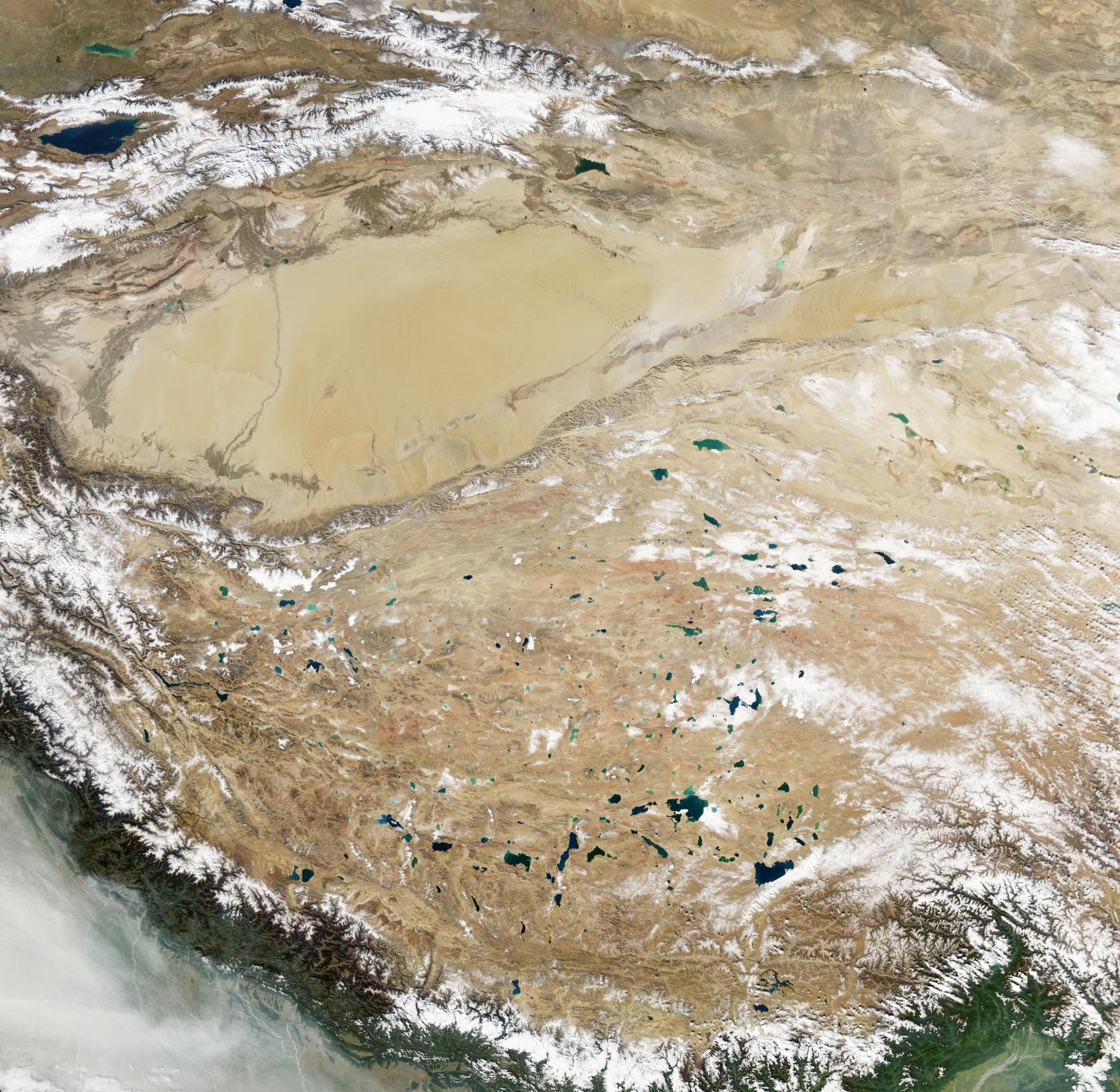

The world’s best astronomical observatories are mainly located in the Western Hemisphere, in high-altitude places like the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii, La Palma in the Canary Islands, and the Cerro Paranal summit in the Atacama Desert in Chile. But there are pristine locations with clear views of the sky in the East, too. And a team of Chinese astronomers are now making the case for building an observatory in the Tibetan Plateau—part of the larger region of Asia that’s commonly called the “roof of the world.”

The group published a new paper in Nature on Wednesday describing the potential they see at the summit of Saishiteng Mountain, near the town of Lenghu in Qinghai province (which is next to Tibet, a region of high political tensions since China first annexed it in 1951).

More than 2.5 miles in altitude, Lenghu “has been known to have unusually clear skies,” says Licai Deng, a scientist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and a coauthor of the new study. “At the same time, the Lenghu area has a spectacular landscape similar to Mars.” Deng says the local government, which is eager to attract tourists interested in astronomy and geography, hired his team to survey the area and see whether it would be a good place to build an observatory.

Four major factors affect how suitable any location will be for astronomical research. The first is whether it tends to have clear skies—that means no dense cloud formations, and very little light pollution. The second is the stability of local air and weather conditions—and what effect the atmosphere will have on optical and infrared observations at night (even the tiniest particles in the air can interfere). The third is whether the site is connected to infrastructure (like power) and can be accessed without too much trouble. And lastly, you want an area where the night sky will be protected from human activity.

High-altitude spots like Lenghu are of great interest to astronomers, since there’s simply less atmosphere to peer through while looking out at objects in space. The researchers monitored the Lenghu area for three years, measuring the darkness of the sky, the weather, the atmospheric conditions, and more. They found that the area scored at least as well on all four factors as other potential sites surveyed in the Tibetan Plateau. In many ways, the researchers think, it could be better than existing sites in Hawaii and Chile. There’s less variability in air temperatures and more stable atmospheric conditions, and the skies are slightly clearer. The amount of water vapor in the air is also low, which is especially useful for infrared observations important to cosmology. About three decades of weather records reveal just an average of 0.71 inches of rain a year. “In this context, Lenghu has the potential to host large facilities,” says Deng.

In the long run, Lenghu may be more protected from the effects of human activity than Hawaii or Chile. The town passed rules in 2017 to preserve the dark sky, so light pollution should remain minimal.

“The results presented for the Lenghu site are nearly as good as those found for Mauna Kea, which is widely regarded as one of the world's best sites,” says Paul Hickson, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, who has previously conducted site testing at Dome A in Antarctica. “One thing that is particularly attractive about this location is the attention given to the control of light pollution.”

In some ways, this new research is an affirmation of China’s current astronomy plans for the area around Lenghu. Those plans include a 2.5-meter imaging survey telescope that began construction this year, a 1-meter solar infrared telescope that will be part of an international array of eight telescopes, and two others at 1.8 meters and 0.8 meters, for planetary science.

As Deng points out, Tsinghua University and the University of Arizona are working together on building a 6.5-meter telescope to operate on the Saishiteng Mountain summit. And there are nascent plans for a 12-meter telescope to be located there as well. “It will be very crowded at the mountain top,” says Deng.

These instruments will go far in getting China on the map where infrared and optical astronomy are concerned—they are on par with some of the “large” telescopes operated in places like Chile. But they still pale in comparison with the “extremely large” observatories being built around the world, like the 24.5-meter Giant Magellan Telescope in Chile, the Thirty Meter Telescope in Hawaii, and the 39.3-meter Extremely Large Telescope in Chile. The type of science these instruments could pull off is expected to inaugurate a new era of astronomy. If China is serious about establishing a more ambitious astronomy program, it will have to catch up pretty fast.

It’s a good thing, then, that it has the Tibetan Plateau. “High, dry, isolated mountains are generally the best places for astronomy,” says Hickson. “There may well be other potential sites, perhaps even better ones, on the Tibetan Plateau that have not yet been explored.”

Deep Dive

Space

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

The race to fix space-weather forecasting before next big solar storm hits

Solar activity can knock satellites off track, raising the risk of collisions. Scientists are hoping improved atmospheric models will help.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.