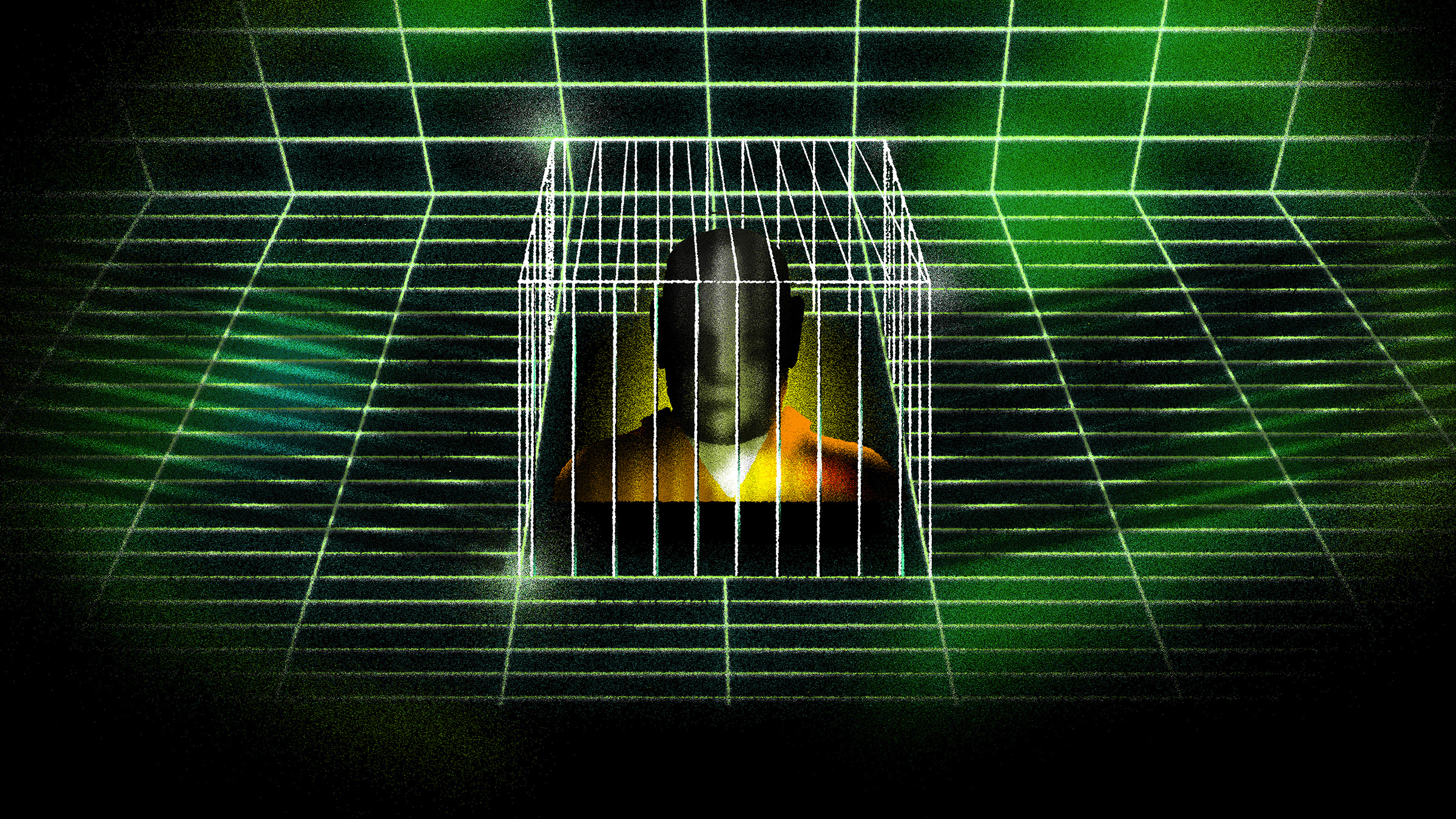

Why prisoners like me need internet access

I haven’t been online in almost two decades. Being able to would help me prepare for life after my release.

California recently promised to provide free computer tablets to all state prisoners by the end of 2021, allowing prisoners like me to email our loved ones through a highly restricted prison messaging service and download content like movies and books. It’s a great first step, but without more open and frequent internet access, there’s no way we’ll ever truly keep pace with the changing world outside our prison walls.

I’ve been locked up since 2003. Back then Apple had barely launched iTunes, and I was still in awe of the so-called high-speed connection I’d paid Time Warner to install in my apartment. In all the years since then, I haven’t logged a single second of internet activity. My frames of reference for what it means to be online now come from network television and print media.

When my first parole opportunity arrives, in 2023, I’ll be 53 years old. As a convicted murderer, I will need to convince the parole board not only that I have been rehabilitated, but also that I am able to be a productive and employable citizen. It can be hard to keep up with changes in technology even when you’re experiencing them firsthand. When you’re locked away, it’s virtually impossible.

I’m hoping to pursue a career path in journalism when I get out of prison, and I worry every day about reentering a global economy with my grossly outdated tech skill set. I know the job market will expect internet fluency more than ever in the post-pandemic world, since much of America’s media workforce has gone remote.

Roughly 2.3 million people are incarcerated in the US. Even though the internet is a given in the rest of society, access in prison is so restricted it’s almost nonexistent. Prisoners are only allowed to use a tiny number of programs that might offer Zoom classes with outside teachers, or to browse an extremely limited set of whitelisted sites through intranets that are carefully cordoned off from the public internet.

Even though the internet is a given in the rest of society, access in prison is so restricted it’s almost nonexistent.

At San Quentin State Prison, where I reside, the computers that prisoners can access feature preloaded interactive programs that offer the same basic experience as reading from a textbook. My only experience using a search engine has been through LexisNexis, which the prison library licenses to allow us to study case law.

In San Quentin’s vaunted coding program, Code 7370, offered through the prison education organization The Last Mile, hand-selected prisoners build and sell actual websites for commercial use. But even they do not have internet access.

As a working journalist in prison, I know I have First Amendment rights, but I’m deprived of a key technology that the United Nations identified a decade ago as a means of exercising one’s freedom of expression.

I understand why government officials, prison administrators, and the public might fear that giving convicted felons real-time internet access would open a Pandora’s box of suspicious activity. Yet if elementary school kids can surf the web safely with parental locks and controls, how hard would it be for someone to design a system that provides incarcerated people with more meaningful access?

In Belgium, for example, an innovative platform called PrisonCloud has offered limited and controlled internet access to prisoners for years. In Finland and Denmark, open prisons, which have minimal security and some of the lowest recidivism rates, also allow limited internet access.

Almost all incarcerated people in US prisons today will be released back into their communities in the future. That includes many of my peers who have been incarcerated since before the advent of the internet.

President Joe Biden has said that the majority of incarcerated Americans deserve a bona fide second chance at life—but we need some form of internet access in order to have a genuine chance of successfully reentering today’s tech-driven society.

Joe Garcia is a correspondent for the Prison Journalism Project at San Quentin State Prison, where he is incarcerated.

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.