Real Madrid

Usually, I spend the month of January teaching an IAP class on Spanish literature in my favorite city in Spain. With travel off the table this year, I took up the challenge of creating an immersive cultural experience online.

Every January 5 since 2015 I’ve braved the crowds lining Madrid’s main boulevard, el Paseo de la Castellana, with my own small crowd of MIT students. Having met me in Spain for IAP, the students begin the Spanish Incubator—my crash course on 20th-century Spanish literature, history, and culture—with a dinner of tapas followed by the annual Three Kings Parade. The students quickly join the fray, competing for caramelos—candies tossed from the parade’s spectacular floats. The next morning, we meet at the Royal Palace, where the regal troops parade past on stately horses. Then we marvel at the Teatro Real opera house and proceed through the winding streets of old Madrid to the Plaza Mayor, once the site of Inquisition autos-da-fé, royal celebrations, and bullfights. We visit the historic San Miguel Market, the “street of authors,” and the huge, beautiful El Retiro park, fortifying ourselves along the way at Madrid’s oldest chocolatería, where even the football players among us cannot finish the heaping plates of churros.

I initiated an immersive Spanish course in Madrid for Independent Activities Period in 2006—MIT’s first regular subject taught abroad—and began offering the Spanish Incubator six years ago. Students live with local families. Some have taken a previous literature or history course; some speak Spanish fluently and others know none, but most can make themselves understood. Each gets a hefty bilingual reader of 20th-century verse, which I design to span everything from early modernist work to the poetry of the Spanish Civil War.

My goals are complex. I want students to understand how artists and writers are influenced by historical and social factors, learn to analyze their own relationship to a work, and come to share my deep love for Spain and its culture.

I use the city as a backdrop. For a unit on Federico García Lorca, for example, we read his “Gypsy Ballads” and visit the Residencia de Estudiantes, where he, Luis Buñuel, and Salvador Dalí lived for 10 years. We read his play Blood Wedding, see the flamenco version of it filmed by Carlos Saura, discuss how it reflects the ineffable passion that Spaniards call duende, and then go to Casa Patas, an intimate venue where my flamenco-loving husband, Stephen Ault, ensures that our students are seated at the edge of the stage. I watch their faces as they are moved by the passionate dance, the haunting singing, and the sounds of the guitar. Now they understand duende. The show begins at 10:30 p.m., and around midnight, our energized group walks to a taberna where a generous friend provides free tapas and drinks. By 2:30 a.m., some MIT students, like true madrileños, head off to discos that don’t close until dawn.

We have class at the historic International Institute building, whose elegant winding marble staircases, intricate wood moldings, beautiful library, garden, and (of course) café provide a welcoming—and markedly European—setting for learning. We gather at 10:30 every morning, take a snack break at noon when students try nearby pastry and fruit shops, and wrap up around 2:30, in time for the Spanish lunch hour. After heading out for lunch (their host families provide breakfast and dinner), the students often return to the Institute library to do their homework. I also use lunchtime to take small groups to favorite cafés, forging bonds that endure long after the course has ended.

Learning about the Spanish Civil War is illuminating for students. They observe the move from surrealism to politically oriented work as writers and artists challenged the rise of Fascism in Europe. They are surprised to learn that the Germans used Spain to test military equipment and techniques like Luftwaffe strafe bombing of civilian populations—and that the great democracies (France, England, and the US) failed to defend the Spanish Republic. They’re amazed that Americans fought in the Spanish Civil War as part of the International Brigades and that poetry appeared in radical journals in the midst of the strife. The course examines the war from the inside through Spanish writing, and from outside through works by Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell. We study a rich archive of battlefield photography by Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. During a long visit to the Reina Sofía Museum, they deconstruct the surrealist elements of Picasso’s Guernica, a mural-size painting that depicts the destruction of a small town by German bombers.

The students travel around Spain most weekends and get to know Madrid deeply. I challenge teams to find and photograph historic spots, such as where Escrivá’s first vision prompted him to found Opus Dei or the convent of the Descalzas Reales, where daughters of the nobility were sent to live out their lives as Carmelite nuns.

When covid made leading an IAP class in Spain impossible this year, I took it as a pedagogical challenge to see if I could transmit the same excitement and intellectual energy while teaching the material virtually. Twice as many students as I could admit applied for the class.

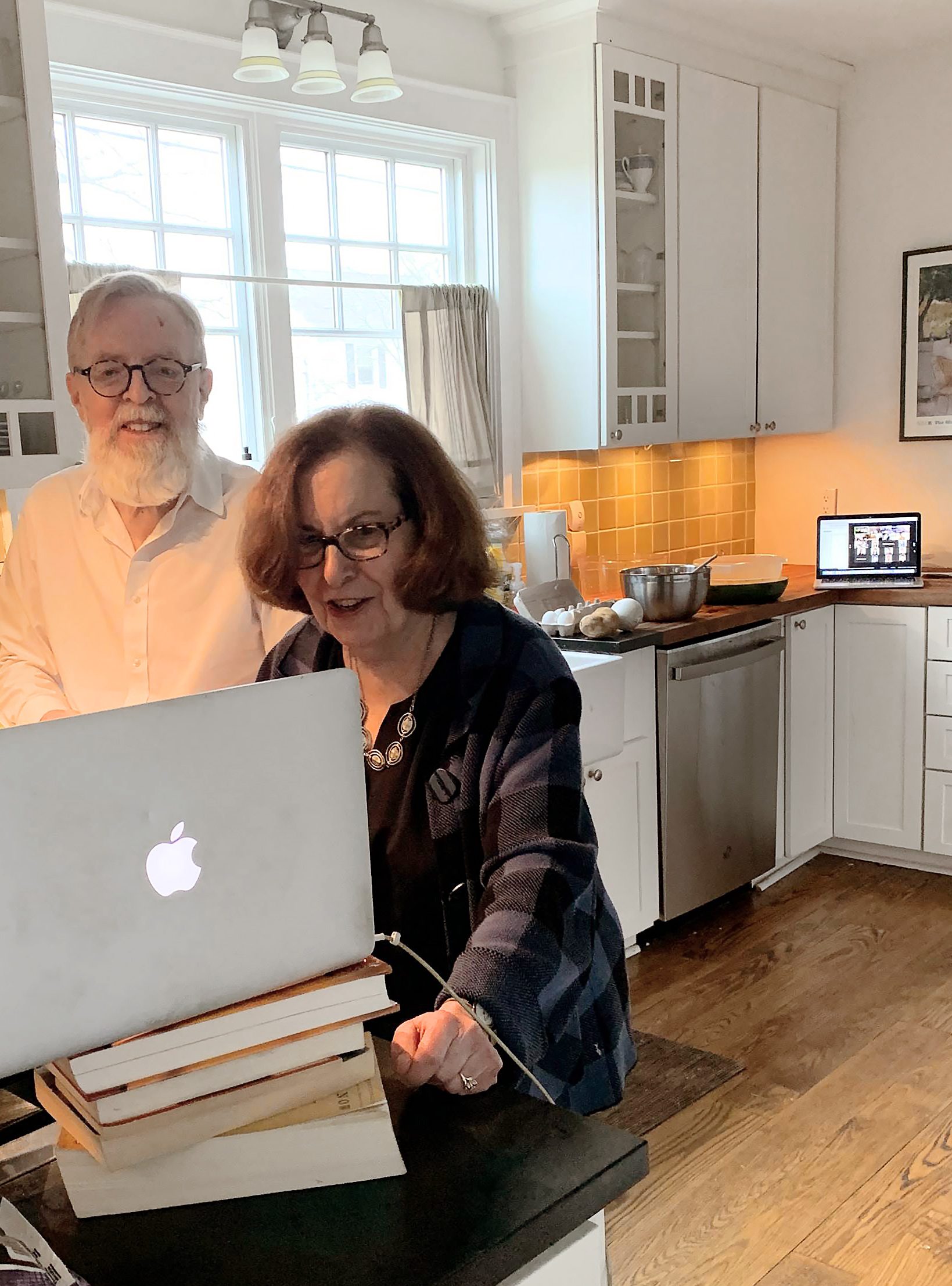

We started with a virtual walking tour through Madrid. Then student teams, each with a different mission, went virtually to specific sites, downloaded images, and came back to class to explain their importance in the city’s history and architecture. We went online to Casa Patas—now closed for good by the pandemic—and saw flamenco by video. I found brilliant online tours of the Reina Sofía, with a new archive of documents about Guernica, as well as a new virtual exhibit at the Prado Museum. Through videos, we witnessed excavations of the remains of Republicans murdered and tossed in unmarked mass graves by Fascist forces. We read aloud the dialogue among military conspirators who seized the Spanish parliament in 1981, holding members at gunpoint. We watched footage of the 2004 terrorist bombing that took 193 lives at the Atocha train station. And instead of enjoying tapas in cafés, we cooked together. My husband taught the students how to prepare tortilla española and espinacas a la catalana in their own kitchens.

I missed bonding with students while spending a month together in what was for them an exotic place, and for me a second home. They did not have to push themselves to understand the señoras with whom they lived, nor did they have to stretch their Spanish to find freshly squeezed orange juice in the supermarkets, locate a bus home at 4:00 a.m., or figure out how to get to Barcelona, Granada, or Segovia for a weekend. At the end of the course, though, all 20 students are now eager to go to Spain and learn more. This year there were no churros, none of the freedom to explore on their own, and no señoras to iron their underwear. Still, I finished the course with a sense not of what my students had lost, but of what they had gained.

Literature professor Margery Resnick has directed IAP classes in Madrid since 2006. She is also president of the International Institute, a Massachusetts educational foundation in Madrid. Founded in 1892 by American missionaries and educators, it’s now a vibrant center for cultural and educational exchange between Spain and the US.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.