Better amputations

MIT researchers invented a technique that preserves crucial muscle communication—and it has even more benefits than expected.

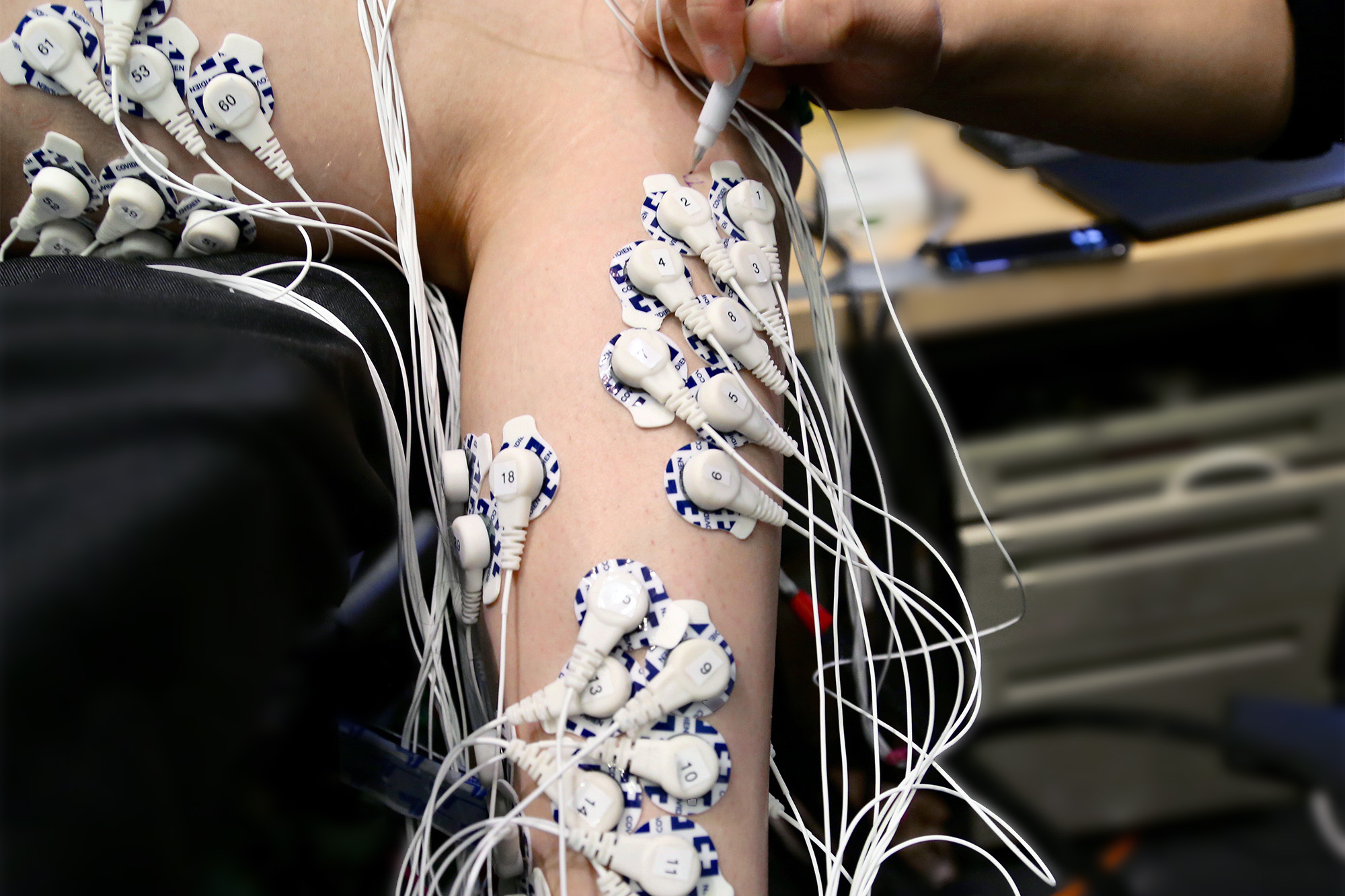

Most amputations sever the muscle pairs that control joints such as the elbow or ankle, disrupting the sensory feedback about the limb’s position in space that would help patients control a prosthesis. But a surgical technique developed by MIT researchers appears to leave amputees with both greater control and less pain than people who have had conventional amputations.

In agonist-antagonist myoneural interface (AMI) surgery, which the Biomechatronics Group led by Hugh Herr, SM ’93, at the MIT Media Lab invented a few years ago, the two ends of the muscle are reconnected so that they still communicate within the residual limb: when one of the pair contracts, the other stretches, sending the familiar signals to the brain.

A study published in February of 15 patients who had AMI amputations performed below the knee found that they could control their muscles more precisely than patients with traditional amputations. Unexpectedly, the AMI patients also reported feeling more freedom of movement and less pain in their affected limb.

“It became increasingly apparent that restoring the muscles to their normal physiology had benefits not only for prosthetic control, but also for their day-to-day mental well-being,” says Shriya Srinivasan, PhD ’20, an MIT postdoc and lead author of the study.

The researchers have also developed a technique to reconnect the muscle pairs in people who have had a traditional amputation. They are working on developing the AMI procedure for amputations at other points, including above the knee and above and below the elbow, and measuring whether the benefits translate to better control of a prosthetic leg while walking.

“We’re learning that this technique of rewiring the limb, and using spare parts to reconstruct that limb, is working, and it’s applicable to various parts of the body,” Herr says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.