How schools plan to close the pandemic education gap

Many students fell behind as a result of remote learning. Now, educators are trying to figure out how to catch them up.

Back before the days of school-by-Zoom, first-grade teacher Andy Granados and her colleagues devoted a lot of effort to planning their time in the classroom. “If you take 10 minutes passing out your materials, that’s 10 minutes of teaching time that you miss,” she says.

Those careful plans seem like a luxury now. These days Granados teaches remotely, watching six- and seven-year-olds try, in their small video boxes, to sound out sh- words like “shop.” Her students attend class for just two and a half hours each school day, but what’s worse is how frequently kids drop out of the call, typically knocked off by poor internet connections.

“It’s really hard. They come back in and don’t know where we are or what page we’re on,” says Granados. She teaches in the Franklin Pierce School District in Tacoma, Washington, where 80% of students come from low-income families. The district gave tablets or laptops to every student and hot spots to their families, but the connection problems persist.

Meanwhile, Granados trudges on. She’s covered about as much of the curriculum as she had by this point in the term when she taught in person, but she doubts her students understand the material as well. “I don’t know what the fix is. It’s really painful,” she says.

It’s clear that US students would be in a far worse position if Zoom, Google Classroom, and other tech platforms weren’t keeping education afloat during the pandemic. But it isn’t working well for everyone, and the heavy reliance on technology is creating greater inequalities across an already uneven playing field. Poor or rural students and those who have a learning disability face the biggest barriers with virtual and hybrid learning. Educators are worried that these students, who were most vulnerable before the pandemic, have been dealt a crippling blow.

The silver lining: the crisis is spurring action to close some of these gaps once and for all.

The price of the pandemic

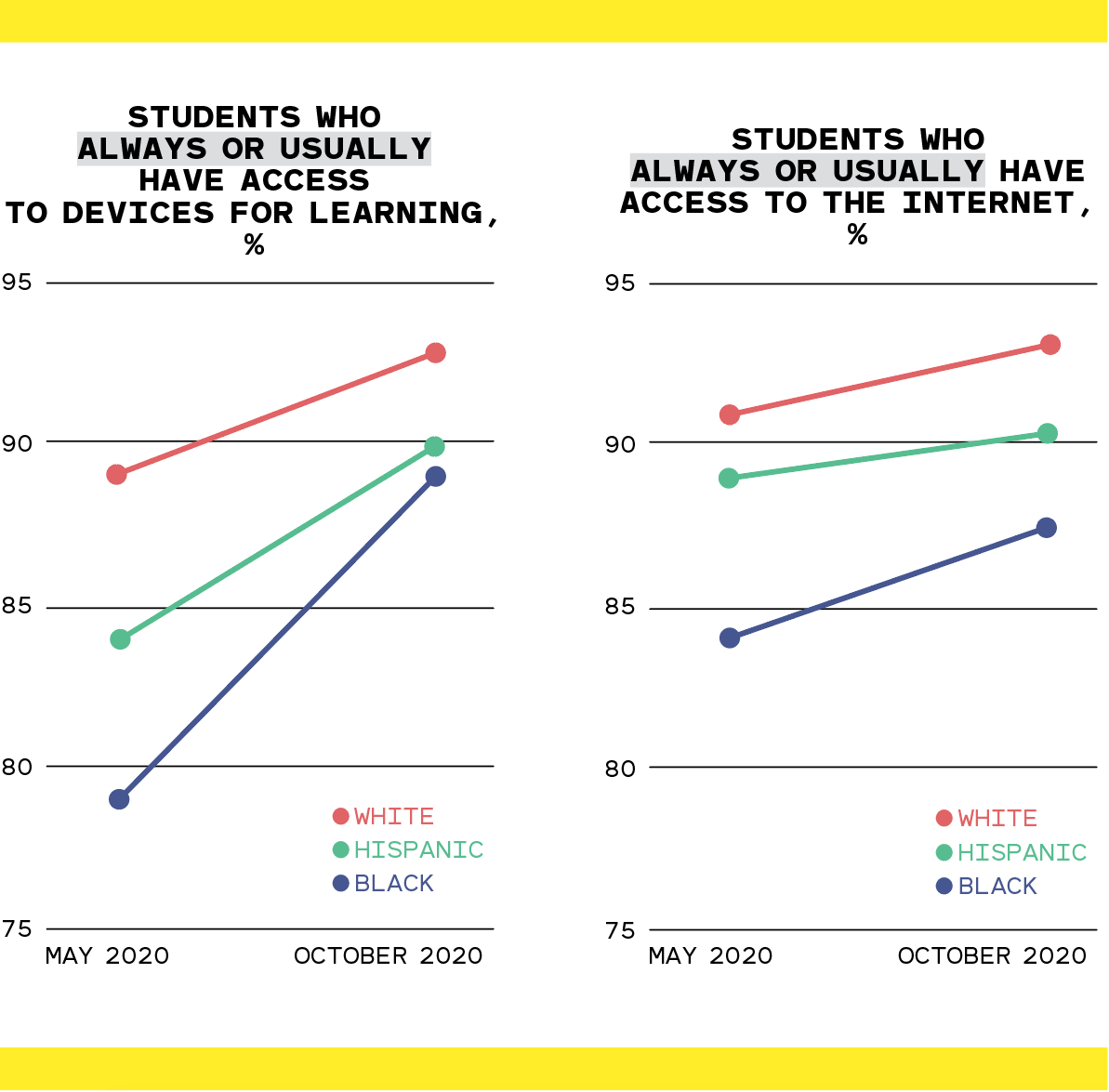

Many school districts made tremendous efforts over the spring and summer to distribute tablets and Chromebooks to students. That closed the digital divide somewhat, but Black and Hispanic households were still less likely than white ones to have reliable internet connections and access to devices, according to October 2020 US Census Bureau data analyzed in a report by the consulting firm McKinsey.

That means a large share of the children who lack the basic tools necessary for online learning are children of color. “And when they do have access, [the devices] are probably of a lower quality,” says Emma Dorn, global education practice manager at McKinsey and a coauthor of the report. Perhaps as a result of these discrepancies, those kids were also half as likely as white students to have had any live contact with their teacher in the past week.

So while white students may finish the current school year between four and eight months behind in math, students of color may be six to 12 months behind, according to McKinsey’s analysis.

Dorn says these disparities stem in part from the lingering digital divide and in part from the fact that students of color are more likely to be learning remotely, according to surveys. Among other reasons, their parents may be keeping them in remote school because of high covid-19 rates in their communities and distrust in authorities who say it’s safe to go back.

Jayda Williams, a high school senior in Providence, Rhode Island, has her own laptop, a school-issued Chromebook, and a stable home internet connection. She’s involved with a student activist group and an art group, which give her purpose. But she’s still struggled more this year than she ever has with school, which she was attending in person for about three days each week as of January.

During her days spent learning from home, Williams has a hard time focusing. She picks up her phone to text friends much more often and misses her social life. “I’m absolutely not learning as much,” she admits. “I don’t think I retain anything.”

Williams’s grades dropped a little during the first quarter, but she still plans to apply to colleges. She’s narrowed her search to schools close to home because she worries college campuses will become coronavirus hot spots once again.

Other high school seniors have been blown further off course. Applications for FAFSA, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, were down 10% as of late January 2021. And enrollment in college was nearly 22% lower in 2020 than the year before. Students who delay college attendance are less likely to complete a degree, studies have shown.

The big question, of course, is how the pandemic will affect students’ educational progress and the broader economy in the long run. The answer is still unclear and will depend in large part on what happens next. But preliminary reports paint a bleak picture.

Dorn and her colleagues have estimated that setbacks in education could cost the average American student $61,000 to $82,000 in lifetime earnings. Again, those averages conceal a stark racial divide: white students’ income could fall by 1.6%, while Hispanic students lose 3% and Black students 3.3% over their working lifetimes. And US GDP could take a 0.8% to 1.3% annual hit by 2040, when most of the current school cohort will be in the workforce.

Laying the groundwork

One conclusion is clear: all students need reliable, high-speed internet at home, and will even when most are back in school. School administrators now see it as their job to make sure students have laptops or tablets and solid broadband connections to use them on.

“You can discuss differences between remote and in-person learning, but remote without the benefit of internet access simply isn’t feasible,” says Phillip DiBartolo, chief information officer for Chicago Public Schools.

Some school districts are trying to close the digital divide once and for all. The Chicago school system partnered with the city and philanthropic groups to launch Chicago Connected in June 2020. The program will provide free high-speed internet for four years to approximately 100,000 students and their families. More than 50,000 families had signed up by January.

Key to Chicago Connected is its partnership with internet service providers RCN and Comcast. The school district signed a data-sharing agreement that provides students’ addresses—with no other identifying information—to the local ISPs, which run a service eligibility check. If an address can be connected to wired broadband, families are given a code to activate the service. If it can’t, the district gives them a wireless hot spot.

Several other cities have launched similar efforts, such as Philadelphia’s PHLConnectED. Eric Gordon, CEO of the Cleveland Metropolitan School District in Ohio, is developing a program that allows the district to pay for students’ internet access as long as they’re in school.

The Chicago model also inspired Evan Marwell, founder and CEO of EducationSuperHighway. The nonprofit and its partners had just achieved their goal of establishing broadband in nearly every classroom building in America. In 2013, only 30% of schools in the US had strong internet connections. By 2020, 99.3% of classrooms were connected to high-speed bandwidth, and Marwell was about to dissolve the organization.

But when covid-19 hit, his phone started ringing. People he’d met, in state capitals and in Washington, asked for advice on getting internet service to students learning at home. After hearing of the Chicago model, he contacted cable and telecom associations to sound them out about replicating it elsewhere.

So far, Marwell and his team have formed agreements with the Internet and Television Association, USTelecom, and others to identify students with no broadband internet at home and to help states and school districts buy it for them.

To close the gap for good, though, efforts like his will need stable funding. In the latest covid-19 pandemic relief bill, Congress provided $3.2 billion for a temporary Emergency Broadband Benefit Program, which will give a $50-a-month discount to qualifying low-income households. Lawmakers could choose to make that benefit permanent.

Another solution could come from the federal E-Rate program, which has been funding broadband in schools. It had about $1.5 billion in unused funds last year. Using that money for students’ home internet access would require the Federal Communications Commission to make rule changes, which it refused to grant under the Trump administration.

Marwell says that with enough funding, the US could close the home digital divide in half the time it took to close the divide in America’s classrooms because so many companies and schools are now focused on this problem.

A holistic approach

On its own, expanding internet access won’t make remote learning work for everyone or do much to remedy the learning loss that’s already occurred.

With the pandemic’s end in sight, educators are discussing how to help the country’s 53.1 million kindergarten and school students make up for lost time. They’re starting to make plans for how to reboot traditional education while preserving the benefits of remote learning.

“To be in person building a connection with a student is the best thing, and to lose that has been really tough.”

Andy Granados

Gordon, of the Cleveland school district, says his staff is considering ways to help students catch up when schools reopen, such as by organizing weekend boot camps, offering evening classes, or grouping students at similar learning levels in mixed-age classrooms.

Researchers also hope to see support for academic interventions such as high-intensity tutoring and summer acceleration academies, with students participating either remotely or in person. The United Kingdom launched a national in-school tutoring program to address learning setbacks due to covid-19, and many education researchers suggest the US do the same. Studies show that frequent, sustained tutoring on top of a student’s regular classes can make a real difference.

DiBartolo, of the Chicago schools, says the pandemic is also opening educators’ minds to new ways of integrating technology into the classroom, but he cautions that this can’t replace human instruction in learning. “At the end of the day it always takes a talented teacher to make it happen,” he says.

Granados, the first-grade teacher, is eager to return to her school once it’s safe. “To be in person building a connection with a student is the best thing, and to lose that has been really tough,” she says. “I think a lot of people are saying, ‘I can’t wait to go back.’”

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.