How an internet lie about the Capitol invasion turned into an instant conspiracy theory

False claims that the invasion of Congress was staged spread at breakneck pace—thanks to activists, the media, and Republican politicians.

Just as well-known, easily identifiable far-right figures livestreamed themselves invading the Capitol in Washington, DC, a lie started spreading around the Trump-supporting internet: What if the mob was actually a group of antifa activists trying to make the president’s supporters look bad? The rumor was false, and debunked repeatedly—not least by the words and actions of the MAGA personalities who were leading the charge in front of a live audience.

The lie had been seeded already, since false claims about antifa are peppered through the history of far-right online spaces. A typical conspiracy theory features an unfounded warning that buses loaded with protesters are being sent to cause trouble in small towns. President Trump himself has repeatedly promoted such claims, helping to turn anti-fascist protesters into go-to villains for his supporters.

That gave fuel to the latest rumor, false though it was. It rapidly made its way through social networks, broadcast news, and online media—and was amplified and supported by some Republican politicians.

According to data from media intelligence firm Zignal labs, at least 411,099 mentions of the lie appeared online in less than 24 hours. The rumor morphed and gained traction as more people contributed subplots, and it swerved through niche platforms and into the mainstream, where a Republican member of Congress blamed antifa for the insurrection.

Mentions about Antifa lie across social media platform

How it happened

As the congressional certification of electoral votes took place on Wednesday, a Trump rally outside the Capitol quickly turned into chaos. At around 2.30 p.m. EST, protesters moved through police lines and mobbed the building.

Around 3:30 p.m., Lin Wood, a well-known right-wing conspiracy theorist, posted on Parler, the social network that is popular among some Trump supporters. He claimed that the mob were antifa supporters, and that two separate images—one of a man from the Capitol mob and the other supposedly from “phillyantifa.org”—showed the same person. The post got 5.6 million views and over 56,000 upvotes. With that, the seed was planted.

An hour later, Wood posted another image on Parler. The second post was an annotated version of the now-infamous photograph of a man standing at the vice president’s marble dais in the Senate chamber. The post had a big red circle over a photographer believed to be Win McNamee of Getty Images, who looked down from the balcony onto the rioter below. Wood claimed that the photographer’s presence was proof of a set-up. The second post got almost as much attention as the first.

From there, the rumor quickly moved beyond Parler onto more mainstream social media websites. Tweets promoting the antifa lie quickly amassed tens of thousands of retweets. Some, like those from Wood’s Twitter account, are no longer available (Wood was permanently banned from Twitter on Wednesday afternoon), but others remain online. At 4:39 p.m. the Trump-supporting televangelist Mark Burns tweeted a photograph of Jake Angeli, a well-known QAnon follower who was part of the group that invaded the Capitol. Burns claimed, “This is NOT a Trump Supporter ... This is a staged #Antifa attack.” Eric Trump, the president’s son, liked the tweet, further distributing it to his 4.5 million followers. Despite its false claim, Burns’s tweet is still available on Twitter, without a disclaimer.

The rumor was spreading on Facebook by midafternoon as well. In various “Stop the Steal” groups monitored by MIT Technology Review, posts featuring annotated images of protesters scrutinized their likenesses, tattoos, and clothing for supposed antifa symbolism. The engagement on the posts was high relative to other content in the groups, and we were able to trace several images and text across multiple groups. Facebook has since removed some of the posts, but many remain.

It was on Facebook that the rumor morphed to envelop other “signs” of antifa involvement. These included claims that rioters with MAGA hats worn backwards were actually antifa supporters, and allegations that such a massive security breach could only be the result of a coordinated setup.

By 5:00 p.m., the rumor was bubbling up to the ears of officials and news organizations. Arizona representative Paul Gosar, a Republican, retweeted a now-deleted message from right-wing campaigner Michael Coudrey that claimed a video of some of the mob wearing knee pads “has the hallmarks of antifa provocation.” Coudrey’s Twitter account has since been suspended.

At 7:45 p.m., Sarah Palin went on Fox news to claim the mob was actually led by antifa supporters, echoing Lin Wood’s original posts on Parler. Fox News host Laura Ingraham continued to amplify the rumors on her show, while niche conservative media outlets like the Washington Times published articles that asserted these lies as truth, including one claiming that a facial recognition company had identified members of the mob. The publication has since retracted its story, but before it disappeared, it had been shared 87,800 times on Twitter and 89,700 times on Facebook, according to Zignal.

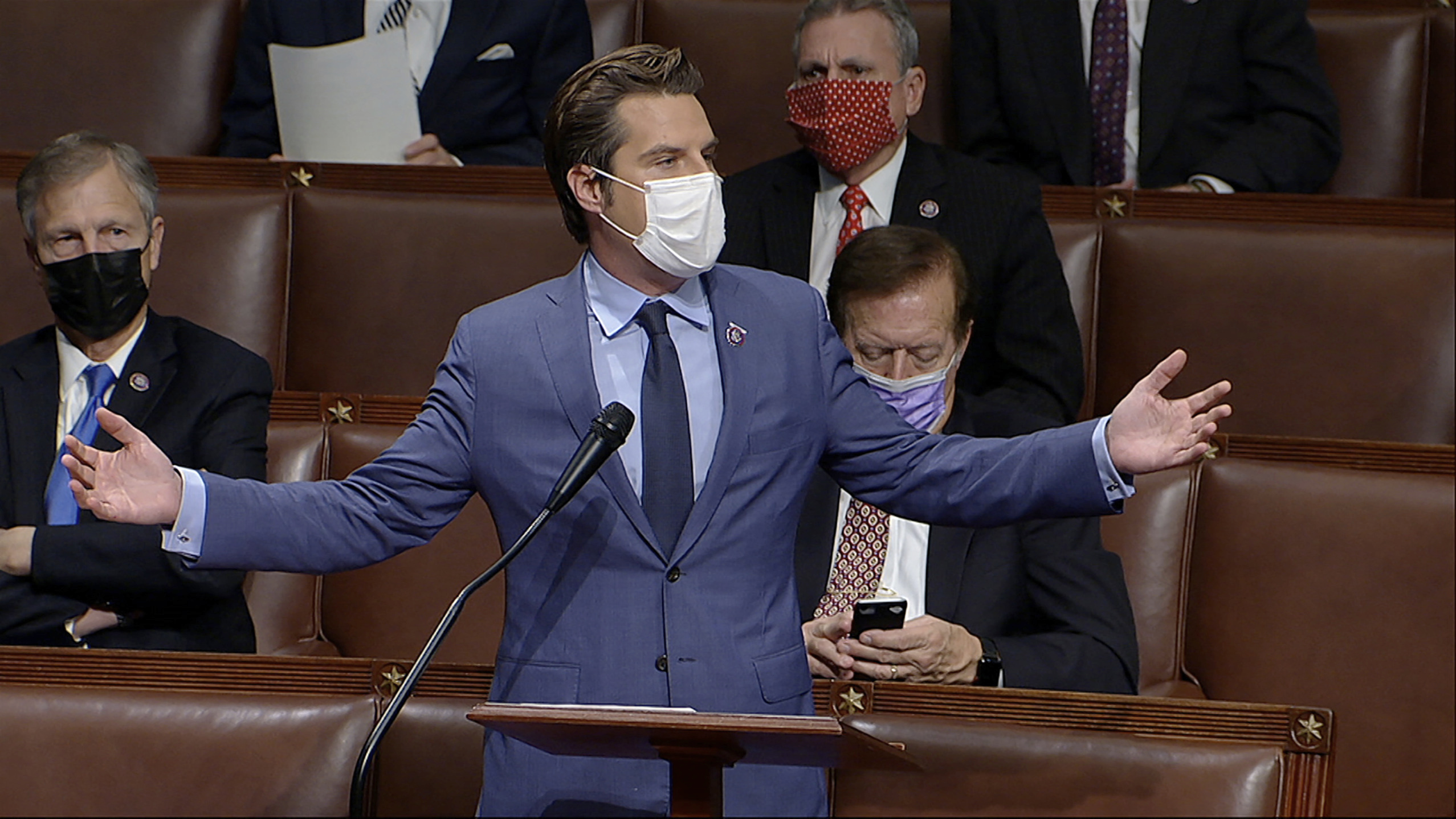

Then, when the invasion was over and Congress resumed in the late evening, Representative Matt Gaetz, a Florida Republican, took to the House floor and blamed antifa during a fiery speech. In it, he claimed that “some of the people who breached the Capitol today were not Trump supporters. They were masquerading as Trump supporters and in fact, were members of the violent terrorist group antifa.”

Gaetz cited the now-deleted Washington Times story to support what he was saying.

And on Thursday morning Republican congressman Mo Brooks tweeted that “fascist ANTIFA orchestrated Capitol attack with clever mob control tactics.” While he claimed to provide evidence of this, his later explanations mostly just referred to other false online rumors and attacked the “#fakenewsmedia.” The thread gained more than 25,000 retweets in a few hours on Thursday and continues to be shared at a brisk pace.

A hint of the future

All this happened even though Trump himself was clear that the Capitol invaders were his supporters, and even though the president had encouraged his followers to go to Washington and disrupt the certification of an election outcome that he falsely claimed was illegitimate.

In fact, the rapid propagation of the Capitol false flag theory hints at what might happen once the president loses power in 14 days—even if moves by Twitter and Facebook to block Trump’s social media accounts become permanent. The network of right-wing conspiracy theorists may perhaps lose one of its most amplifying and strategic voices, but it does not need Trump to remain dangerous.

Even when they viewed events with their own eyes on Wednesday, during one of the most disgraceful moments in modern American history, the ecosystem of Trump supporters, right-wing media outlets, and some politicians instead chose to believe something that sounded better to them—whether it was a lie or not.

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.