The biggest technology failures of 2020

This was a year we needed technology to save us. A pandemic raced over the land, there were wildfires, uneasy political divisions, and we gasped in the miasma of social media. In 2020, the ways in which technology can help or hurt never seemed clearer.

In the success column we have covid-19 vaccines. But this article is not about successes. Instead, this is our annual list of the worst technology flops and failures. Our tally for 2020 includes billion-dollar digital business plans that faceplanted, covid tests that bombed, and the unforeseen consequences of wrapping the planet in cheap satellites.

Covid tests

The polymerase chain reaction is not a new technology. In fact, this technique for detecting the presence of specific genes was invented in 1980, and its inventor won a Nobel Prize a decade later. It’s employed in a vast array of diagnostic tests and laboratory research.

So it counts as a historic screw-up that at the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic, the specialized laboratories of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent states lab kits with wrong ingredients that didn’t work. So began the failure to stop the pathogen, the sidelining of nation’s top public health agency, and, more broadly, the unexpected inability of the country that invented PCR to get coronavirus tests to everyone who needs one. Widespread and frequent testing is what economists said would be the swiftest, cheapest way to keep the country up and running. Even now, 11 months later, lines and delays are still the testing norm in the US, even as private labs, universities, and health centers run approximately two million tests per day.

Read more:

Stop covid or save the economy? We can do both, MIT Technology Review

The CDC’s failed race against covid-19: A threat underestimated and a test overcomplicated, Washington Post

Unregulated facial recognition

Imagine a grainy video from a convenience store robbery. A shoplifter looks at the camera and presto, police use face recognition to identify a suspect. Now imagine a city—like Portland, Oregon—that decides it has to ban police from doing that.

The ability to match faces is one of the signal triumphs of the new generation of artificial intelligence, and the technique is appearing everywhere. That includes settings where its use can seem intrusive or unfair, like schools or public housing. The result this year: a run of bans and restrictions by cities, states, and companies that could stifle one of the first and most significant results of superhuman AI.

The reason the technology is accelerating is that cameras are everywhere—and we all handed over our selfies. “We have allowed the beast out of the bag by feeding it billions of faces, and helping it by tagging ourselves,” says Joseph Atick, who built an early face recognition system using special cameras and a custom image database. Now there are hundreds of face recognition programs crunching pictures online. Controlling these systems, says Atick, “is no longer a technological issue.”

Over the summer, Microsoft and Amazon both denied police access to their face-matching systems, at least temporarily, and cities like Portland enacted sweeping bans that also stop hotels and shops from identifying people. What’s still missing is a national framework to guide right and wrong uses. Instead of a cycle of abuses and bans, we need policy. And in the US, we don’t have it yet.

Listen to more: Attention, Shoppers: You’re Being Tracked, In Machines We Trust podcast

Quibi’s quick collapse

“Quick bites. Big stories.” That was the motto of Quibi, a Hollywood-powered streaming service that set out in April to revolutionize entertainment with 10-minute shows for phone screens.

But the big story ended up being Quibi’s fast demise. Six months after its debut, the company was firing talent and giving what remained of its $1.75 billion budget back to investors.

The misfire reminded us of journalism’s infamous 2018 “pivot,” in which news sites reassigned reporters en masse to manufacture ultra-short text-on-screen videos before brutally firing everyone. Similarly, Quibi was using well-paid pros to make slick $4.99-a-month subscription content that competed with YouTube, TikTok, and hordes of creators who film cat videos and dance moves for free.

In a farewell letter, studio mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg and Quibi CEO Meg Whitman said their pursuit of a “new category of entertainment” might have been misguided, but they also directed blame at the pandemic, which kept people at home in front of the TV. “Unfortunately, we will never know, but we suspect it’s been a combination of the two,” they wrote. “Our failure was not for lack of trying.”

Read more: Quibi Is Shutting Down Barely Six Months After Going Live, Wall Street Journal

Mystery microwave weapon

Since 2016, several dozen US diplomats and spies in Cuba and China have been hit by a spectrum of painful and strange neurological symptoms. They’ve woken to sharp noises and experienced loss of balance and a feeling of pressure in the face. The most plausible cause of their torment, according to the National Academies of Sciences: a microwave weapon.

No one can say for sure if a directed beams of pulsed radio energy aimed into diplomats’ homes and hotel rooms are to blame for “Havana syndrome.” The US was slow to recognize and investigate the pattern of injuries and still can’t name a cause with certainty. What is clear is that anyone using a microwave weapon in deliberate attacks has failed to think things through. Other powers, including the US, can also generate powerful, invisible beams to cause headaches, clicking noises inside the skull, nausea, and hearing loss. The clandestine use of such over-the-air technology, the academies said, “raises grave concerns about a world with disinhibited malevolent actors and new tools for causing harm to others.”

Some weapons just shouldn’t be used.

Learn more: “An Assessment of Illness in U.S. Government Employees and Their Families at Overseas Embassies,” The National Academies Standing Committee to Advise the Department of State on Unexplained Health Effects on U.S. Government Employees and Their Families at Overseas Embassies

#zoomdick

Have you ever had a dream where you show up at work or school in your underpants? With Zoom, it’s entirely possible.

During the pandemic, the video app became our new office, our schoolyard, and our way to socialize. With it came the hazard of broadcasting what should remain private. There was the toilet flush as the Supreme Court held oral arguments, and the Mexican senator who changed her top on video without realizing it.

Gross-out humor turned to tragedy in the case of prominent CNN and New Yorker legal critic Jeffrey Toobin, who allegedly exposed his genitalia to coworkers as he fumbled between a work Zoom and a pornographic interlude. Many said Toobin deserved to be fired by the New Yorker, citing the #metoo movement (#metoobin became the hashtag). Others sympathized with an all-too-human situation. “There but for better camera work go I,” they seemed to be saying.

Read more: New Yorker Suspends Jeffrey Toobin for Masturbating on Zoom Call, Vice News

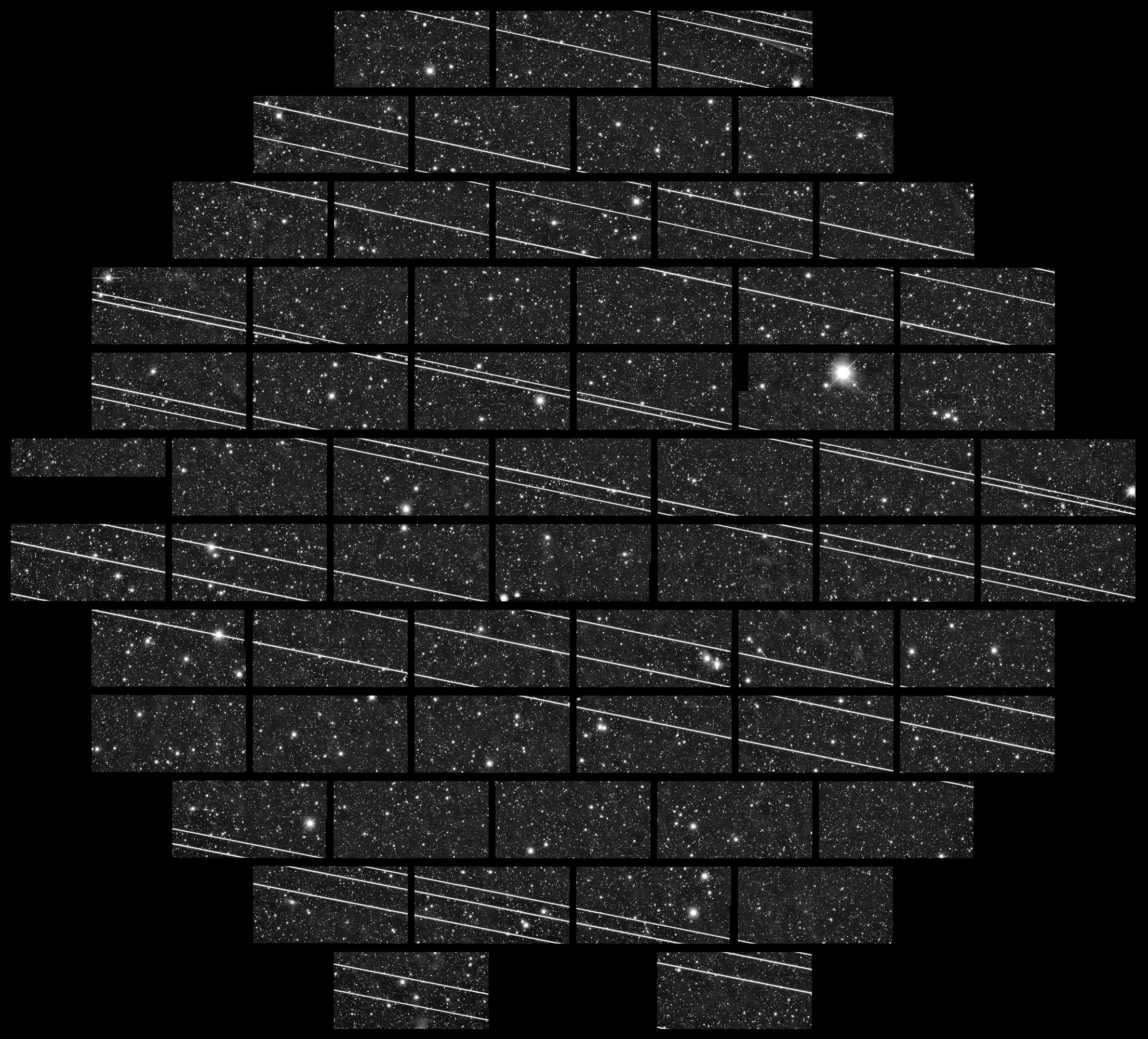

Light pollution from satellite megaconstellations

Since prehistory, humankind has looked upwards for awe and inspiration, to imagine what forces created the world—and which might end it.

But now, that cosmic view is being contaminated with the reflections of thousands of inexpensive commercial satellites put aloft by companies like Amazon, OneWeb, and SpaceX, who want to cover the Earth with internet connections. Sixty satellites can swarm out of a single rocket.

The problem for astronomers is that sunlight reflects from the satellites, which race by at low altitudes at dawn or hover overhead, perpetually illuminated. Their sheer numbers pose a problem. SpaceX plans to launch 12,000 of its Starlink satellites, while other operators plan 50,000.

Concern is greatest for wide-field optical telescopes sitting atop mountains, whose job includes detecting exoplanets or near-Earth objects that could collide with our planet. Now there’s an after-the-fact attempt to fix the problem. SpaceX tried coloring a satellite black, but it heated up too fast. More recently, the company started equipping satellites with sunshade visors to stop the reflections.

Read more: Satellite mega-constellations risk ruining astronomy forever, MIT Technology Review

Learn More: Impact of Satellite Constellations on Optical Astronomy and Recommendations Toward Mitigations, NSF NOIRLab

The vaccine that make you test positive for HIV

We knew things could go wrong with the rushed vaccine effort against covid-19, but the fate of Australia’s homegrown candidate was still a surprise.

A team at the University of Queensland and the biotech company CSL developed a promising protein vaccine that seemed to be working well in people. But its main innovation was its downfall: it used two bits of HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) as a “molecular clamp” to help it inside cells. As a result, researchers discovered, volunteers who got the shot were turning up positive on common HIV tests. Those false positives created a chance for confusion and controversy, and conspiracy theorists would be certain to sow doubts over the vaccine.

The Australian team made some heroic efforts to correct the problem, but to no avail. In early December, the government admitted defeat and canceled a $750 million order for 51 million shots, making it the first advanced covid vaccine project to get scrapped. Compare that with the situation in the US, which authorized or approved several treatments against the coronavirus that don’t work, or where evidence is lacking. Sometimes admitting failure is the better course. “This is the scientific process working,” Australia’s health minister said.

Read more: Australian vaccine abandoned over false HIV response, BBC

Cyberpunk 2077

The creators of the most anticipated video game of 2020 promised players a sci-fi dystopia. Instead, they delivered a world broken in all the wrong ways. The immersive universe of Cyberpunk 2077 was beset with problems from day one. Players (in particular, those playing on consoles) encountered a ton of glitches ranging from hilarious to game-breaking. Sony pulled the game from PlayStation stores a week after its release, offering full refunds for anyone who wanted one.

The reviews of the game aren’t bad—some are even positive. And even in a virtual world, everyone makes do. The bugs and glitches that make the game unplayable are now part of the fun: try riding a motorcycle by standing on it pantless, or teleporting at random when you jump in a car.

Read more: Cyberpunk 2077 Was Supposed to Be the Biggest Video Game of the Year. What Happened? New York Times

Hydroxychloroquine, the covid drug that never worked

You knew things were getting strange when Rudolph Giuliani tweeted, late-night infomercial style, that a malaria drug called hydroxychloroquine was “100% effective” against covid-19.

Indeed, a chorus of right-wing figures—cartoonist Scott Adams, Fox News hosts, and flag-bearing avatars on social media—were all convinced the cure had been found.

Early on, in March, the old and plentiful drug did make the list of possible covid-19 treatments. But studies quickly showed it didn’t actually help. By then, though, what the studies said didn’t matter. That’s because the drug was promoted (and even taken) by Donald Trump, who—as Politico wrote—sought a silver bullet for the political problems caused by the pandemic. What he called “the hydroxy” was going to be that bullet. “A lot of good things have come out about the hydroxy, a lot of good things. You'd be surprised how many people are taking it,” Trump said.

At first the pressure to declare a cure paid off. The US Food and Drug Administrations authorized the drug’s use, and the federal government ordered pallets full. But as the nonexistent evidence was replaced by the results of clinical trials (which found no benefit and even some heart risk), covid’s fakest drug faded from view. Giuliani’s tweet was removed by Twitter. The FBI arrested a doctor selling $3,995 “survival packs” that included the drug. Trump, when he eventually fell ill with covid-19, received every treatment his doctors thought might help.

That did not include hydroxychloroquine.

Read more: The Strange and Twisted Tale of Hydroxychloroquine, Wired

—Abby Ohlheiser contributed reporting and analysis.

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.