Your first lab-grown burger is coming soon—and it’ll be “blended”

Growing meat in a lab is still way too expensive. But mixing it with plants could help finally get it onto our plates.

One cool fall night 10 years ago, Jessica Krieger went for a run to clear her head. Krieger, then an undergraduate in neuroscience, had just watched a documentary that showed the gruesome ways many animals are slaughtered for food. “The animals were terrified, in pain, dying,” she recalls.

Krieger was already worried about the meat industry’s contribution to climate change, and the documentary convinced her to stop eating meat for good and become vegan. It also compelled her to try, in vain, to persuade her friends and family to do the same. But she wanted to do more—so she decided to get radical.

“I felt really helpless and hopeless about protecting animals and the planet,” she says. “That wasn’t a good feeling. So I preferred to pursue a crazy idea than do nothing.”

Krieger threw herself into what at the time was a fringe area of biotech research: growing and harvesting edible animal cells without killing any sentient creatures. There had been a lot of talk—and some interesting results, including a lab-grown hamburger that cost as much as a house to create—but making a dent in the commodity meat industry was not remotely on the menu.

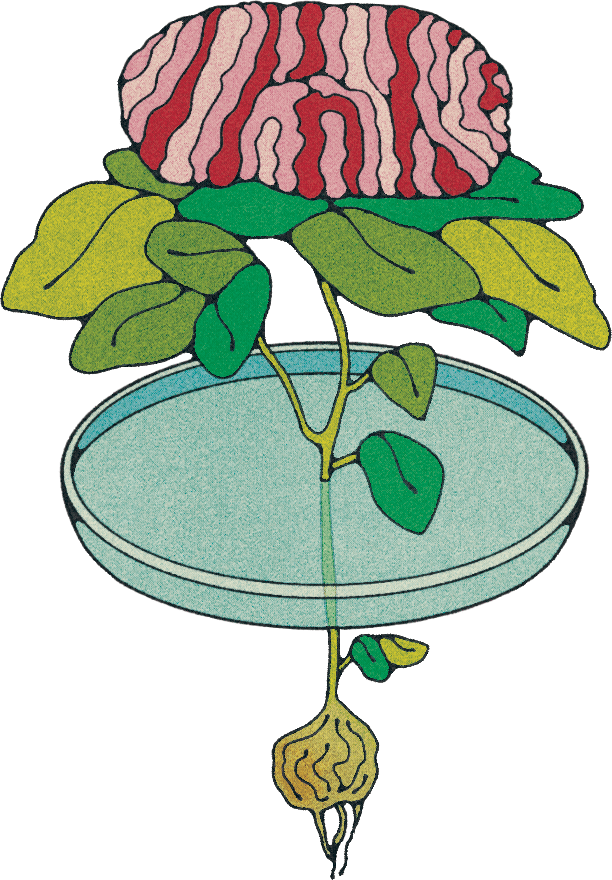

Today, though, things look a bit different. Cultured meat (or, if you prefer your high-tech foodstuffs seasoned with a bit more marketing savvy, “cultivated meat”—the industry now eschews phrases like “lab-grown” or “in vitro”) is already a nascent industry. The product is still exorbitantly expensive compared with old-fashioned meat, you can’t yet buy it at the supermarket, and for the most part it doesn’t look or taste much like the real thing. At least not on its own. That’s where the startup Krieger cofounded, Artemys Foods, comes in.

While lab-grown meat was busy trying to find its way out of the petri dish, plant-based meat substitutes were undergoing a revolution. Firms such as Impossible and Beyond Meat broke through to the mainstream by cleverly mimicking the flavor and texture of ground beef, pork, and chicken using vegetable proteins and fats. These days you can pick up an Impossible Whopper at Burger King and Beyond Meat sausages in supermarkets in dozens of countries.

That kind of competition could be seen as bad news for cultured-meat startups. But Krieger and a number of other entrepreneurs think it’s the opening they need to finally bring their creations to market—in the form of “blended meat,” melding the best of the plant-based and cultured-meat substitutes. Even the world’s biggest fast-food firms are interested: KFC has announced it will be working to produce blended chicken nuggets that could be available this year.

Regardless of who gets there first, blended meat is coming, and it might not be long before you get a chance to taste it.

Tastes like chicken?

In terms of industry buzz, cultured meat has never been hotter. At the end of 2016 there were just four firms working on it, according to a report by nonprofit The Good Food Institute. By early 2020, that number had jumped to at least 55 startups around the world trying to re-create at least 15 different types of animal flesh, including pork, shrimp, chicken, duck, lamb, even foie gras.

The process for making these products has come a long way since Mark Post, a researcher at Maastricht University, had his $320,000 lab-grown burger cooked on television in 2013—but it essentially follows the same principles. A small sample of cells is taken from an animal, usually via biopsy, and then fed a broth of nutrients. When millions of new cells have grown, they are encouraged to differentiate into muscle cells and eventually strands of muscle fiber.

The technology’s promise is to reproduce the flavor and texture of meat without harming animals, and without the huge environmental costs of rearing them. Proponents also point out that cultured meat won’t carry diseases or need antibiotics, which breed drug-resistant bacteria.

Investors are biting. Memphis Meat, one of the biggest players, announced an infusion of $161 million in January 2020. It plans to open its first pilot factory in 2021 to produce its wares at scale (it has already created versions of beef meatballs, chicken, and duck). Many others, such as BlueNalu (fish) and Meatable (pork and beef), have also raked in substantial sums.

Another sign of the industry’s growing maturity is that a second tier of companies have sprung up to specialize in certain aspects of the process: developing better-quality growth media or novel bioreactor designs, for example, or just collecting and banking useful stem-cell lines from different animals. From the hype, the press releases, and the promotional videos—in which actors delightedly sample minuscule strips of flesh in fashionably lit restaurants and homes—it might seem as if the first cultured product is just months away.

But there’s a problem. The medium that nurtures the cells is expensive. The cost is dropping from the early days, when startups in the R&D stage relied on repurposed cell culture media taken from biomedical research. But growth media still make up the bulk of production expenses—estimates range from 55% to 95% of the total—and a kilogram of cultured meat still costs hundreds of dollars. Even allowing for eventual economies of scale as factories get up and running, it’s no recipe for success. No wonder, then, that cultured-meat firms have started thinking about how to get a piece of the huge market that plant-meat companies have opened up.

“When I was looking at the costs associated with 100% cell-based products, they were astronomical,” says Krieger. “And I also was becoming more and more impressed with the burgers that Beyond and Impossible had come out with. It seemed like a natural fit.”

Artemys, which has recently come out of stealth, expects to announce private taste tests of the Artemys Burger any day now: a hybrid burger made from cultured beef cells mixed with plant-based proteins. Earlier this year the team ran an experiment, combining its cell-based beef with a store-bought plant-based burger. “It was really incredible,” says Krieger. “It was like the missing link when it comes to meat alternatives.” For her, the cells added “umami flavor” to the plant burger and increased its juiciness—all for a much lower price than a pure cultured burger.

That cost saving is also appealing for Benjamina Bollag, founder and CEO of Higher Steaks, a startup based in Cambridge, UK, that has been focusing on cultured pork. She says she’s still deciding whether the firm will launch with blended products, but so far her team has experimented with making pork belly and bacon from a mixture of cultured pork cells and plant products. The pork belly was around 50% cultured cells, while the bacon was 70% cultured, says Bollag. The rest was mostly plant proteins.

Bollag and Krieger are unusual in the cultured-meat world in openly treating a hybrid or blended product as a welcome first step—desirable, even. For many, the mission to create 100% meat analogues from scratch is, ostensibly anyway, still paramount. Behind closed doors, it’s likely a different story, however. “Even if they don’t say it publicly, the vast majority of the cultivated-meat prototypes you may have seen in the news are in fact hybrid products,” says Liz Specht, associate director of science and technology at the Good Food Institute.

Fast-food chains have no such idealistic notions about purity. In July, KFC announced that it was planning to start selling hybrid chicken nuggets: 20% cultured chicken cells, with the rest from plants. To make the nuggets, the company said, it is pairing with 3D Bioprinting Solutions, a Russian firm that in 2019 helped 3D-print a cultured-meat sample on the International Space Station.

The nuggets will be created by first putting down a layer of extruded plant protein engineered to produce a more realistic meat-like texture instead of a kind of slurry. A layer of cultured chicken will follow, then another plant layer, and so on. Then this mixture will be shipped off to KFC’s kitchens, where the nuggets will take shape and be coated in the Colonel’s secret seasoning.

The first taste tests for the KFC blended nuggets are due to take place early in 2021. “The market is ready,” says Yusef Khesuani, 3D Bioprinting Solutions’ CEO.

Muscle memory

If you think about it, there’s nothing new about blended meat. Ground-meat products like sausages, nuggets, and burgers have always been a mashup (McDonald’s has said one of its burgers can contain beef from over 100 cows), often mixed with breadcrumbs and other ingredients. That’s because even conventionally produced meat is expensive. Bulking it out makes for a cheaper product that’s still full of meaty flavor.

For big, traditional meat firms, that can be good for business and attractive to the growing number of people who want to eat less meat but aren’t ready to give it up entirely. Tyson’s “Raised and Rooted” line of sausages and nuggets blends real meat with pea proteins to appeal to such flexitarians in the US. And Perdue Farms has its own line of blended products that include “Chicken Plus” nuggets, voted the best nuggets in the US by the Food Network in 2020. The “plus” is plant material supplied by the Better Meat Company. “Think about it: the number one best-tasting frozen chicken nugget in America is only 50% chicken,” says Paul Shapiro, Better Meat’s founder.

Shapiro believes foods like the hybrid nuggets will help cultured-meat companies get a foothold with consumers. “The first cultivated-meat products on the market will be blended,” he says. “That’s what I’m predicting. Cultivated meat is still hundreds of dollars a pound. Better Meat Company formulas are closer to $2 a pound.”

When you bite into a piece of meat you encounter fats, connective tissue like collagen, that juice dripping down your chin … it’s all part of the sensory experience.

But besides cost, there’s another reason for blending cultured meat with plants. Meat is mostly muscle, but from a flavor perspective, muscle is a relatively minor player. When you bite into a piece of meat you encounter fats, connective tissue like collagen, that juice dripping down your chin … it’s all part of the sensory experience. Eating pure muscle tissue—which is what most cultured meats are right now—is liable to feel like gnawing on a hunk of shoe leather.

This is where the advances in plant analogues can help. Scientists at Impossible and the Better Meat Company have perfected techniques for adding ingredients like coconut oil and sunflower oil to create moisture in their burgers and sausages. Plant ingredients, used expertly, can help make early cultured-meat products taste and feel more like the real thing.

“We’re able to enhance that chew so when you bite down you get that pushback and satiating feel of biting into a piece of meat,” Shapiro says.

That’s important, because there are an awful lot of meat-lovers like me who will need to be convinced. And for the moment, plant-based products could still do with a helping hand in one crucial area of the gustatory experience.

Fat: where the flavor's at

Ah, fat. Villainized for decades, it’s still avoided by many of the health-conscious among us. But true foodies know that it’s responsible for so much of what we love about food. In her hymn to good cooking, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, the chef and writer Samin Nosrat describes fat as the element that “carries flavor.”

“Without the flavors and texture that fat makes possible, food would be immeasurably less pleasurable to eat,” she writes.

For all the terrific advances by the likes of Impossible, plant-based meats that substitute plant fats for animal tissue get close but don’t quite convince the palate. Call it a fatty uncanny valley.

That’s why some cultured-meat startups have turned their attention, for now, away from trying to reproduce an entire hunk of meat from scratch and toward the aspects of meat that impart the most flavor.

Fat is the focus for Peace of Meat, a startup based in Antwerp, Belgium, that aims to provide high-quality cultured fats, particularly duck and chicken fat, to other players in the industry. The company’s biologists extract stem cells from a fertilized chicken egg, cultivate them, and then grow fat cells in a bioreactor.

“The protein part of plant-based meats is actually pretty good,” says founder David Brandes. “But when you bite into it, you suddenly feel like it’s soy. Those products are missing the magic ingredient: animal fat. That’s what drives texture and flavor.”

Make no mis-steak

One evening in early October my wife and I went to Hawksmoor, a steakhouse in central London. It was our wedding anniversary and our first night in a restaurant since the pandemic lockdown began. For all the very many good reasons to eat less meat (environmental, ethical, health), steak still has that special-occasion tag. When it came, the T-bone we chose was beautifully charred from the grill on the outside, and pink, sweet, and succulent inside. It was juicy, packed full of flavor—in a word: heaven.

Cultured meat is years, if not decades, from delivering anything that approaches such an experience. Most cultured prototypes are closer to the consistency of ground meat. But if and when something approximating a real steak hits your plate, there’s every chance that it will be a hybrid.

In November, Krieger left Artemys to found a new blended-meat startup, Ohayo Valley. Instead of a burger, Ohayo Valley will be working on making a full steak, complete with marbled fat, out of a combination of plants and beef cells. She says she hopes to have the first taste tests of the steak later this year.

Eat Just, a firm based in San Francisco, is working on chicken nuggets that were granted regulatory approval to be sold to consumers in Singapore in November. Eventually, it plans to create a full chicken breast made of nothing but cultured meat. Like my steak, a chicken breast gains its shape and texture from a complex mix of elements, including collagen, elastin, and tendons. Re-creating all of this in a bioreactor is no simple task.

“A 100% product would be an amazing thing, and I believe we will get there—it’s just a lot more difficult,” says Nate Park, the firm’s director of product development and a former gourmet chef. In the meantime, Park and his team are working with edible, plant-based scaffolds that can act as connective tissue. “We have these beautiful systems we already understand,” he says. “We can take our cultured mass and apply the two things together. It’s like a chocolate-and-

peanut-butter situation.”

This is also the vision of Israeli firm Aleph Farms. Its proof-of-concept steaks, first shown at the end of 2018, don’t look quite ready to take on my Hawksmoor T-bone—but they’re recognizably meat, at least. Aleph, which partnered with 3D Bioprinting Solutions on the stunt aboard the International Space Station, expects to open its first production plant by the end of 2021, according to CEO Didier Toubia.

Toubia says the trend toward blended products is here to stay. “I believe in convergence,” he says. “There will not be competition between plant and cultured meat; there will be collaboration and integration between the different solutions.”

Finger-licking' good

The Good Food Institute’s report estimates that cultured products will compete with certain premium meats, like bluefin tuna or foie gras, within the next three years. By the 2030s, hybrid products might be able to undercut the cost of conventional meat, especially as the plant-based-meat industry grows in parallel, according to Specht. An analysis by management consultancy Kearney estimates that cultured meat, in some form, could take as much as 35% of the global meat market by 2040. The dream of animal-free meat is, it would seem, getting closer to reality.

It’s clear that blended products will have to pave the way. But even ignoring the substantial technical obstacles that remain, a big question looms: Will consumers like these foods? The image of meat grown in giant vats, monitored by scientists in lab coats, has a distinct sci-fi ick factor that doesn’t compete well with the cachet of organic, farm-to-table meat from animals that have spent their lives dancing in pastoral bliss.

"We’re not going to stop causing the enormity of harms we do to animals because we care about chickens and pigs—it’s going to be because we create a new technology that renders the current system obsolete.”

Blended meat might, then, do one final job for the cultured-meat industry: help it gain acceptance. People who are already pretty comfortable with the idea if not the flavor of plant burgers will soon get to try them with a sprinkling of cultured cells to add some extra meaty oomph—an Impossible Plus, perhaps. Many of the people I spoke to suggested that this might win the average customer over more easily than an entire lab-grown meat product.

That’s the hunch Krieger’s been working from ever since her run that night. And it’s one more and more people in the industry share.

“Facts alone don’t change people’s behavior,” says Shapiro. “We didn’t stop exploiting horses because we cared about horses; we stopped using them because new tech came along that rendered their exploitation obsolete. We’re not going to stop causing the enormity of harms we do to animals because we care about chickens and pigs—it’s going to be because we create a new technology that renders the current system obsolete.”

That system of raising and then slaughtering animals has stood for millennia and won’t be easily upended. Cultured meat—first blended, and then in pure form—will only stand a chance if it tastes at least as good as traditional meat. Krieger, for one, is gung-ho. “I think there’s going to be a huge shift in consumer perception once people actually get to try cell-based products,” she says, “and realize they taste amazing.”

Correction: The documentary was not produced by The Good Food Institute, but one of its founders. We have amended the reference.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.