The weirdly specific filters campaigns are using to micro-target you

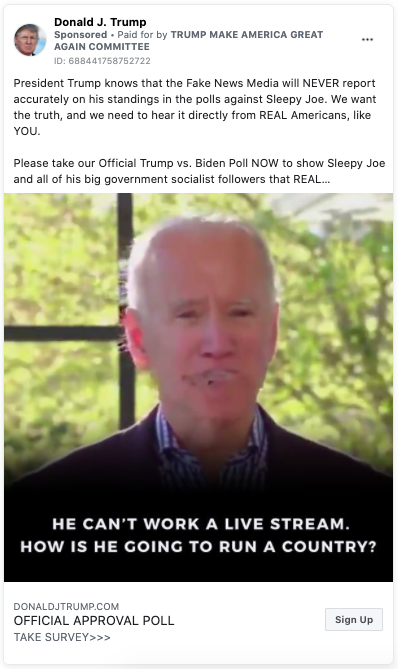

The news: The NYU Ad Observatory released new data this week about the inputs the Trump and Biden campaigns are using to target audiences for ads on Facebook. It’s a jumble of broad and specific characteristics ranging from the extremely wide (“any users between the ages of 18-65”) to particular traits (people with an “interest in Lin-Manuel Miranda”). Campaigns use these filters—usually several on each advertisement—to direct advertisements to segments of Facebook users in attempts to persuade, mobilize, or fundraise. The data shows that both campaigns have invested heavily in personality profiling using Facebook, similar to the tactics Cambridge Analytica claimed to employ in 2016. It also shows how personalized targeting can be: campaigns are able to upload lists of specific individual profiles they wish to target, and it’s clear from the study that this is a very common practice.

How targeted ads work: Campaigns create voter outreach strategies by using models that crunch data and spit out predictions about how people are likely to vote. From this they identify which of those segments they hope to raise money from, persuade, or turn out to the polls. Facebook, meanwhile, provides advertisers with a set of ways to target those users including basic demographic filters, a list of user interests, or the option to upload a list of profiles. (Facebook creates the list of subjects that users might be interested in based on their friends and online behavior.) Campaigns use personality profiles to match their segments to the Facebook interests.

When campaigns upload lists of specific users, however, it’s much less clear how they have identified whom to target and where the profile names came from. Campaigns often purchase lists of profile names from third parties or create the lists themselves, but how a campaign matched a voter to a Facebook profile is excruciatingly hard to track.

The data: The data isn’t comprehensive or representative, as it comes from about 6,500 volunteers who have chosen to download the Ad Observatory plugin. Facebook doesn’t publish this data, so voluntary sharing is the only window into this process. That means it’s hard to draw a fair comparison between the campaigns or take a broad look at what they are doing. Working with the Ad Observatory team, we were able to pull out some examples of filters and the ad pairing served to that targeted audience, included in this story. You can explore the rest of the data at the bottom of this dashboard.

How to interpret it: The NYU researchers say there are some insights to be gleaned. First, it’s clear campaigns are continuing to experiment and invest in targeted advertising campaigns on Facebook. The researchers also said that advertisements created with custom lists tended to be used for persuasive messaging. It’s unclear exactly why this is, but there is a lucrative industry around finding and messaging to voters who might be persuadable.

Most of the ads created using the specific filters around interests were meant for fundraising purposes, though not exclusively. Fundraising ads are targeted to base supporters, so it could be that campaigns have more sophisticated models (and better data) when it comes to the interests and personalities of their own supporters.

What this means for political microtargeting: In 2016, Cambridge Analytica was accused of using Facebook data to create personality profiles of potential US voters. It claimed to identify those people likely to be persuaded to vote for Trump on the basis of this personality mapping. There’s no evidence that it worked, but Laura Edelson, an engineer at Ad Observer, said, “I don’t actually know of any evidence that it’s not effective, either.” She noted, “It could be ineffective and still harmful.” The continual investment into this kind of profiling and segmenting indicates that this kind of data-driven, large-scale microtargeting has only grown and become more mainstream.

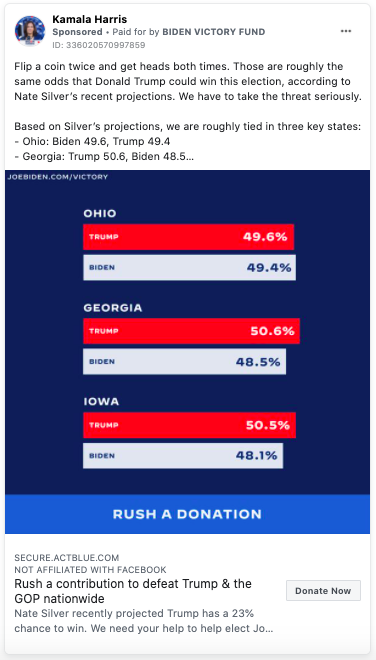

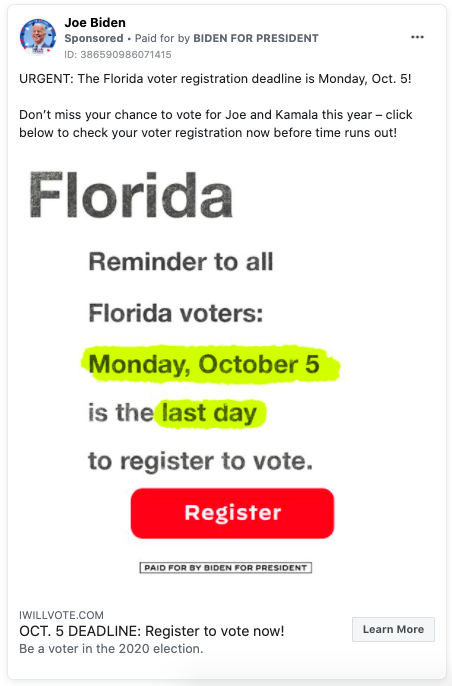

Biden campaign ad created using the filter "interested in: NPR and/or the Democratic Party in Florida"

What next: We may not be able to get these kinds of insights for much longer: The Wall Street Journal reports that Facebook has written to the researchers behind the Ad Observatory warning them that the project is in violation of its terms. Because the tool scrapes data from the site, the report claims, the social media platform said the project must be shut down and all data deleted or NYU "may be subject to additional enforcement action." Researchers have long argued that Facebook limits visibility into activity on its site: CrowdTangle, one of the main tools for measuring activity on Facebook, was acquired by the Palo Alto company in 2016.

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.