Letter-writing staved off lockdown loneliness. Now it’s getting out the vote.

For the past couple of years, Courtney Cochran hosted a Nashville-based meetup group called the Snail Mail Social Club. Before the pandemic, it involved people gathering, pen and paper in hand, to write letters together. “It was a fun social endeavor,” Cochran says. “You got some face-to-face connecting time with people.”

When the coronavirus made meeting impossible, a friend suggested she set up a pandemic version. So she started an Instagram account, offering to connect potential pen pals. Shut In Social Club was born.

It blew up—so much so that Cochran had to create Google sheets and forms to help match up writers. And when the American Association of Retired Persons ran a feature on pandemic pen pal programs in its magazine, she had “a deluge.” She says she has already matched hundreds of people. As we talk, she gasps while she’s scrolling through sheets: “Lord, a lot of people still need to be matched up!”

Of course, there’s nothing new about writing letters. But a combination of social distancing measures and a volatile political year has made the traditional act of putting pen to paper suddenly more attractive than just shooting an email or an emoji-filled text. Beyond Instagram-fueled social projects for people in quarantine, letter writing has become a form of retro-political activism to help get out the vote.

“It’s a thoughtful and generous act”

The isolation we all felt during lockdown has been a central theme for many of the letter-writing projects that sprang up in recent months. For example, Dear Loneliness was brainstormed over Zoom by three students as an interactive art project in which people write letters about their experiences with isolation and upload pictures of them to the site to create a constantly evolving, public-sourced gallery.

Since June, Dear Loneliness has collected about 35,000 letters. “We’ve been really surprised by the similarities between some of them,” Sarah Lao, one of the student cofounders, says. “We’ve read through quite a few letters about Zoom, suffocating family dinners, the role of sound and music, birthdays and anniversaries, and racially charged encounters. When we look at everyone’s nationalities, it becomes clear that we’re all more similar in how we experience loneliness than we might expect.”

While Instagram was home to many mail art accounts pre-pandemic, interest in writing letters—and documenting them online—has grown. In a report published in April about the impact of covid-19 on the US Postal Service, 17% of people reported sending more letters and postcards than usual. More than half of respondents agreed that sending letters gave them a unique connection with the recipient.

“It’s a thoughtful and generous act,” says avid letter writer Caroline Weaver. “You have no control over how long a letter takes to get to someone. You’re putting your faith in the universe to get this beautiful piece of communication out where it’s going.”

Write, stamp, vote

But letter writing is about more than just nostalgia, connection, or whimsy. Weaver—the owner of CW Pencil Enterprise, a pencil shop in New York, and a lifelong lover of stationery—has always been a letter writer. She says she generally sends about 40 letters a month, and she documents mail art frequently on her and her store’s Instagram. But recently, she’s been sending 100 letters a week as a form of activism—to members of Congress about Breonna Taylor’s murder, to family members to urge them to vote, and more. She’s even created a Google doc of addresses to make it easy for people to send letters to politicians.

Letters have an advantage over clicking automated forms online, she says. “They [congressional staff] can’t ignore it,” she says. “They can ignore an email, but they have to open and read and log a letter.”

In the US, even sending mail that’s not explicitly political has become an inherently political act.

The USPS had always been financially strapped, and this year matters got worse. In May, Louis DeJoy—who’d never held a position in the postal service—was appointed postmaster general. Almost immediately, he slashed overtime; coupled with social distancing measures, this led to widespread (and, in many areas, continued) delivery lags. During this election year, that gave rise to questions and worries about mail-in voting in the midst of a pandemic.

One result has been calls to #savetheusps by buying stamps and writing more letters. In April Christina Massey, a Brooklyn-based artist, created Artists for the USPS, an Instagram-driven group that connected amateur and professional artists in pairs, all as part of a move to help support the service. One person would start a piece of mail art and then send it to a recipient, who would finish it. Writing a letter became a patriotic act, and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez went so far as to propose a (yet to be seen) national pen pal program in her Instagram stories.

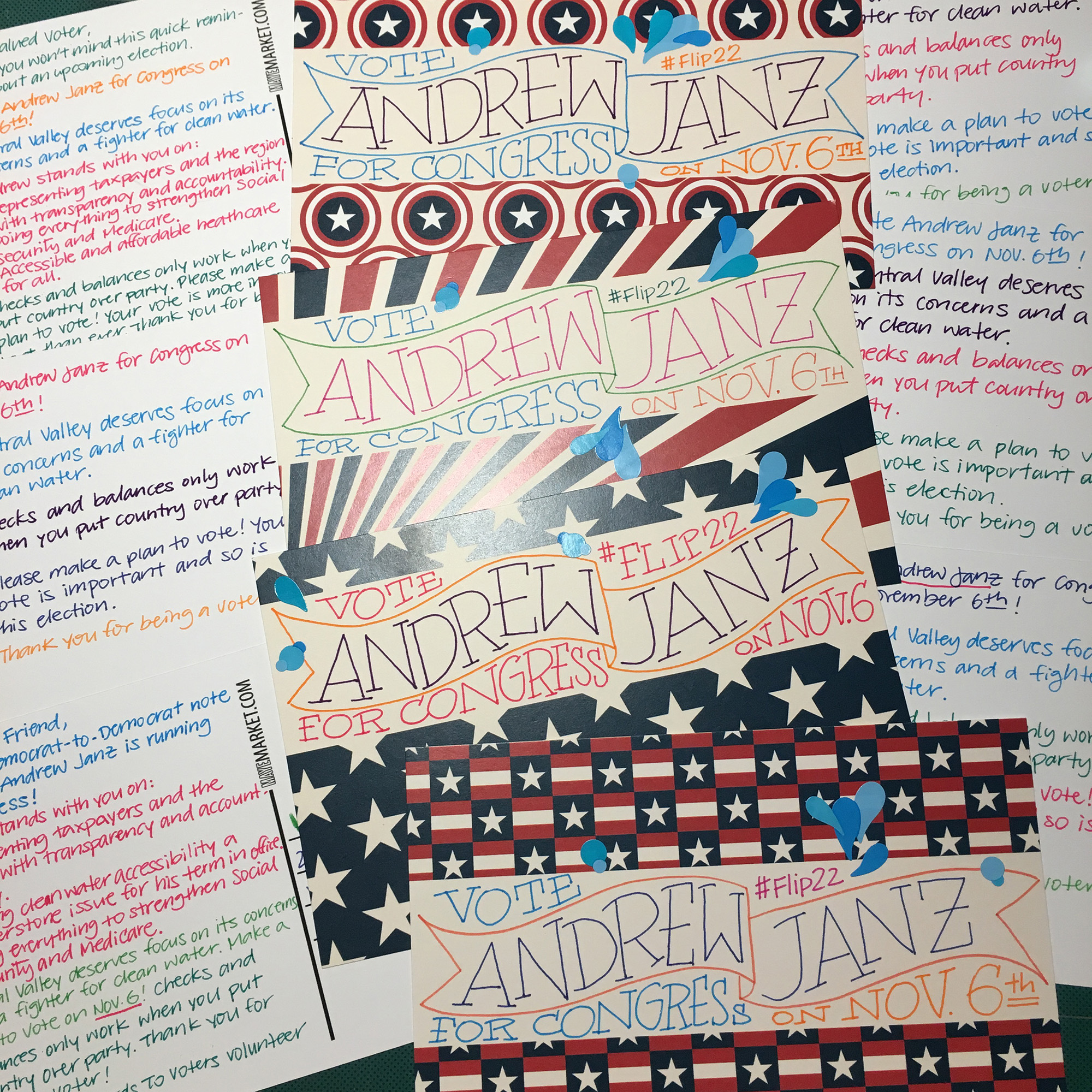

Meanwhile other groups have been using organized letter-writing to urge voters to the polls in November. In April, a coalition of progressive organizations organized the Big Send. The idea is that volunteers sign up to write letters, stamp them, and hold them until late October, when they will be sent en masse to battleground-state voters across the country.

That might sound insane in 2020—why not send text messages? Emails? Even flyers? Especially in the midst of mail delivery chaos?

“It’s a noisy information environment,” says Scott Forman, the founder of Vote Forward, one of the organizations behind the Big Send. “Once you open a letter and you see that a fellow citizen cared enough to spend five minutes of their time and 60 cents in supplies to send you this thing and it’s respectful and personal, that’s an entirely different weight, and it feels more significant.”

Forman carried out his own experiment to see if it worked. In 2017, he accessed public voting records and hand-wrote 1,000 letters to Alabama voters, urging them to vote in a special election for a US Senate seat. He compared voter turnout rates with a control group of 6,000 people who didn’t get letters. Forman’s informal analysis showed that people who got the letters were more likely to vote.

Forman tried this method again in 2018’s midterm elections. This time, he worked with colleagues and volunteers to write letters from home. Letter receivers voted at rates of “one to three percentage points higher,” he says, “which might not sound like a ton, but that's pretty competitive with get-out-the-vote initiatives.”

After this voting cycle, he’ll have a lot of data points to play with. “We have tens of thousands of users, and volunteers are writing exponentially now, at about 140,000 letters a day over the last two months,” Forman says. On September 9, the Big Send announced they’d reached 5 million letters, with about a month to reach their goal of 10 million in all. Forman is confident they will.

Much of this type of activity has been driven by Instagram, where stories and posts encourage young people to sign up and write letters to get out the vote.

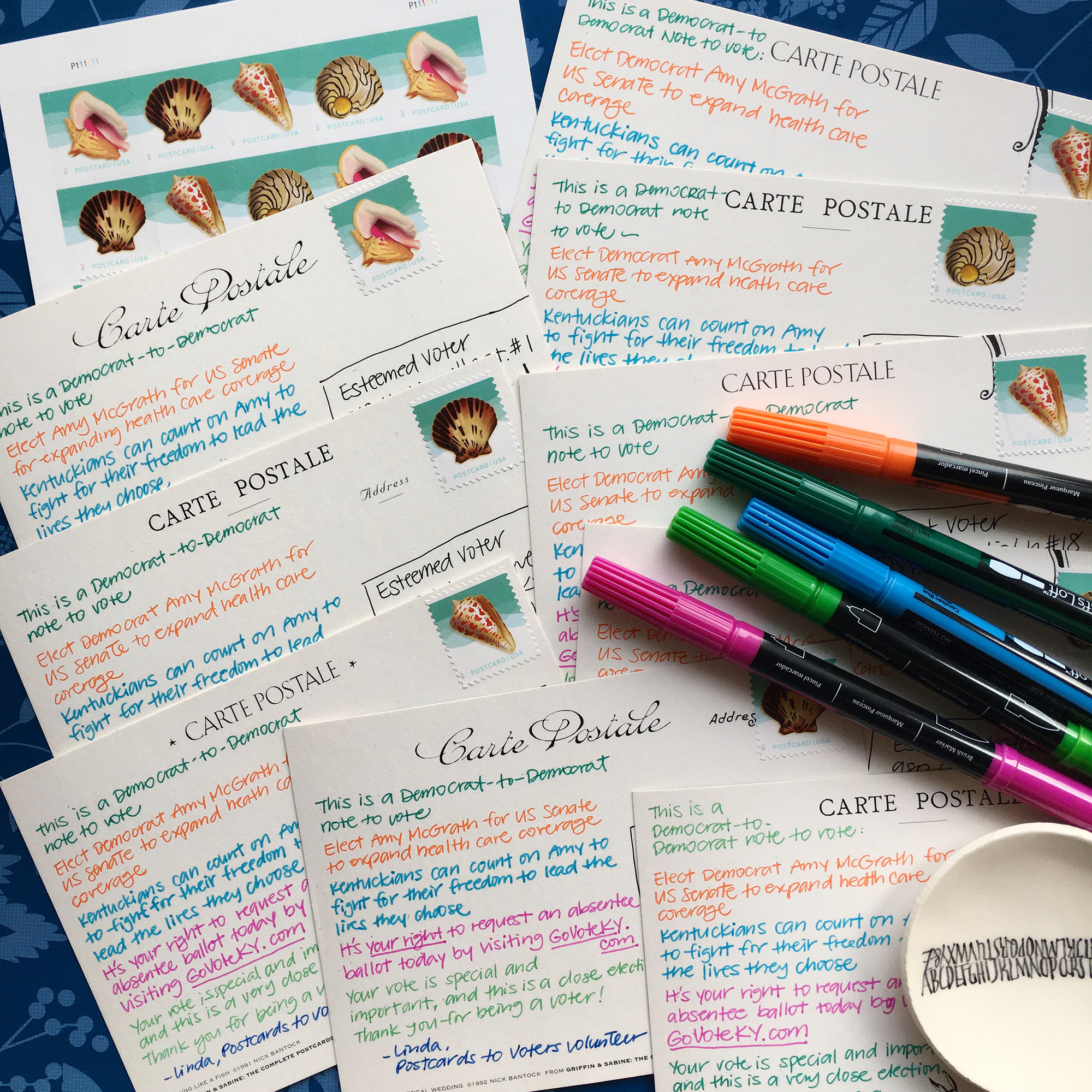

It’s not only letters. Postcards are also fast gaining popularity as Instagrammable activism. The Sunrise Movement, a youth climate-change initiative, is aiming to send 1 million postcards to voters (as of this writing, the postcards are sold out).

Postcards to Voters is a similar effort, with a bot that sends voter addresses to volunteer writers. According to the founder, Tony McMullin, 660,000 postcards have been sent so far, and the group is well on its way to exceeding the 2 million postcards sent in 2018.

For him, postcards have clear advantages. “They’re only 35 cents [per card, compared with 55 cents for a standard letter],” he says. “I think of postcards as an open-face sandwich: You know what’s inside without any effort. You [the postcard] won’t be eyed with suspicion [as a piece of junk mail]. It’s less intimidating. It’s short—it doesn’t take a long time to read.”

Like Vote Forward, the group is heavily female. It leans older but has a wide spectrum of ages, from teens to the elderly. Zoom marathon sessions are common, and users are encouraged to Instagram their work.

Linda Yoshida—arguably Instagram’s most prominent calligrapher, with 19,000 followers—has been sending postcards to representatives since 2017, embellishing them with gorgeous calligraphy and documenting them on her Instagram account.

That’s partly a strategy. “I hope my calligraphed envelopes stand out in the Capitol Hill mailrooms and make staffers open them first, and my postcards to voters get a second glance rather than being tossed into the junk mail pile,” she says.

And that’s ultimately what makes snail mail possibly more powerful than an email or text. During a divisive election season amped up by a pandemic, the ability to connect is valuable. It’s universally available, it’s affordable, and it can be as simple as a note scrawled on a postcard or as complex as a work of calligraphy. And with a quick upload onto Instagram, it’s an easy, effective way to push for policy change while stuck at home.

As Weaver says, “Never underestimate the power of a written letter. It’s a bigger thing than just letter writing.”

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.