Elon Musk’s Neuralink is neuroscience theater

Rock-climb without fear. Play a symphony in your head. See radar with superhuman vision. Discover the nature of consciousness. Cure blindness, paralysis, deafness, and mental illness. Those are just a few of the applications that Elon Musk and employees at his four-year-old neuroscience company Neuralink believe electronic brain-computer interfaces will one day bring about.

None of these advances are close at hand, and some are unlikely to ever come about. But in a “product update” streamed over YouTube on Friday, Musk, also the founder of SpaceX and Tesla Motors, joined staffers wearing black masks to discuss the company’s work toward an affordable, reliable brain implant that Musk believes billions of consumers will clamor for in the future.

“In a lot of ways,” Musk said, “It’s kind of like a Fitbit in your skull, with tiny wires.”

Although the online event was described as a product demonstration, there is as yet nothing that anyone can buy or use from Neuralink. (This is for the best, since most of the company’s medical claims remain highly speculative.) It is, however, engineering a super-dense electrode technology that is being tested on animals.

Neuralink isn’t the first to believe that brain implants could extend or restore human capabilities. Researchers began placing probes in the brains of paralyzed people in the late 1990s in order to show that signals could let them move robot arms or computer cursors. And mice with visual implants really can perceive infrared rays.

Building on that work, Neuralink says it hopes to further develop such brain-computer interfaces (or BCIs) to the point where one can be installed in a doctor’s office in under an hour. “This actually does work,” Musk said of people who have controlled computers with brain signals. “It’s just not something the average person can use effectively.”

Throughout the event, Musk deftly avoided giving timelines or committing to schedules on questions such as when Neuralink’s system might be tested in human subjects.

As yet, four years after its formation, Neuralink has provided no evidence that it can (or has even tried to) treat depression, insomnia, or a dozen other diseases that Musk mentioned in a slide. One difficulty ahead of the company is perfecting microwires that can survive the “corrosive” context of a living brain for a decade. That problem alone could take years to solve.

The primary objective of the streamed demo, instead, was to stir excitement, recruit engineers to the company (which already employs about 100 people), and build the kind of fan base that has cheered on Musk’s other ventures and has helped propel the gravity-defying stock price of electric-car maker Tesla.

Pigs in the matrix

In tweets leading up to the event, Musk had promised fans a mind-blowing demonstration of neurons firing inside a living brain—though he didn’t say of what species. Minutes into the livestream, assistants drew a black curtain to reveal three small pigs in fenced enclosures; these were the subjects of the company’s implant experiments.

The brain of one pig contained an implant, and hidden speakers briefly chimed out ringtones that Musk said were recordings of the animal’s neurons firing in real time. For those awaiting the “matrix in the matrix,” as Musk had hinted on Twitter, the cute-animal interlude was not exactly what they hoped for. To neuroscientists, it was nothing new; in their labs the buzz and crackle of electrical impulses recorded from animal brains (and some human ones) has been heard for decades.

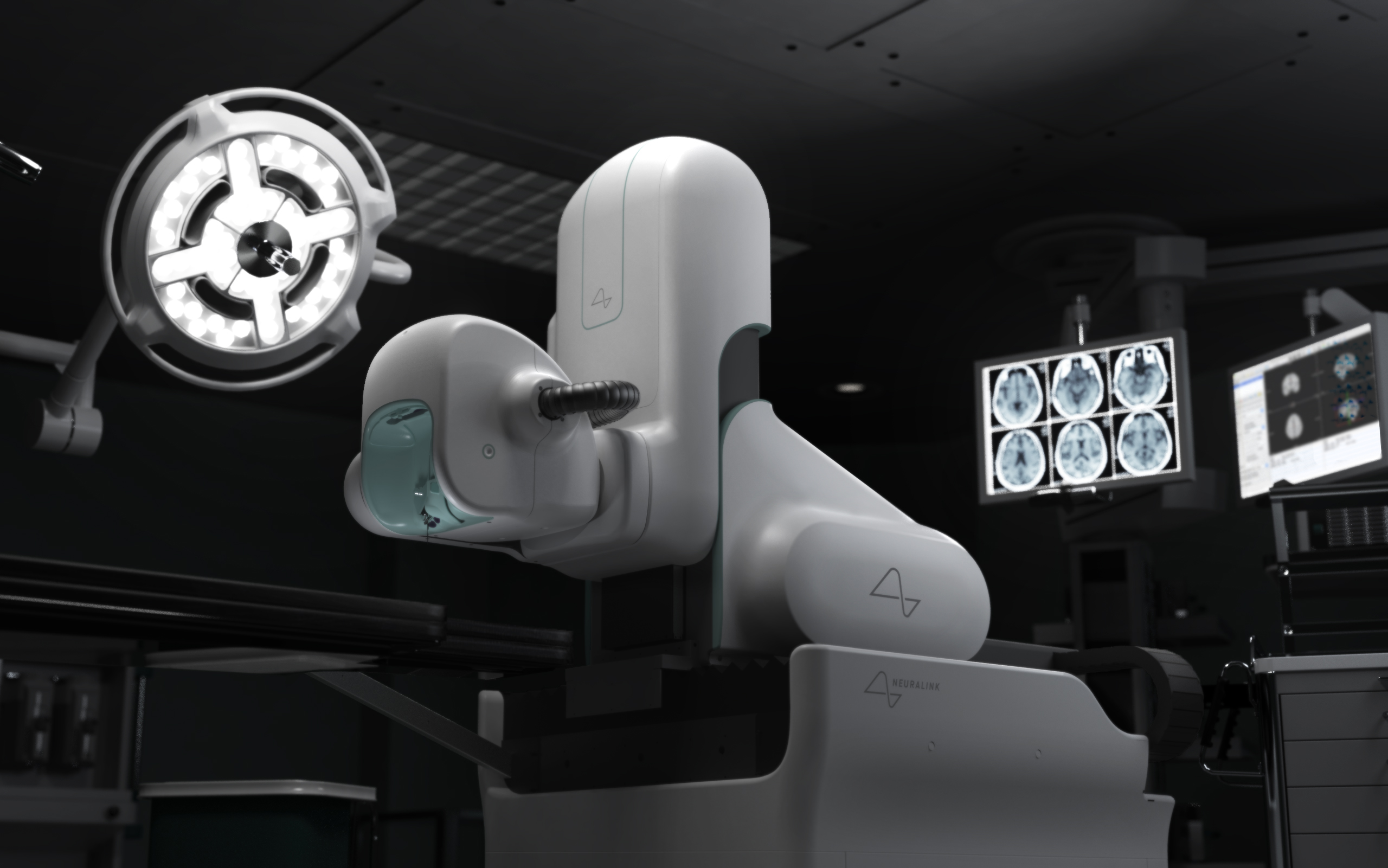

A year ago, Neuralink presented a sewing-machine robot able to plunge a thousand ultra-fine electrodes into a rodent’s brain. These probes are what measure the electrical signals emitted by neurons; the speed and patterns of those signals are ultimately a basis for movement, thoughts, and recall of memories.

In the new livestream, Musk appeared beside an updated prototype of the sewing robot encased within a smooth, white plastic helmet. Into such surgical headgear, Musk believes, billions of consumers will one day willingly place their heads, submitting as an automated saw carves out a circle of bone and a robot threads electronics into their brains.

The futuristic casing was created by the industrial design firm Woke Studio, in Vancouver. Its lead designer, Afshin Mehin, says he strived to make something “clean, modern, but still friendly-feeling” for what would be voluntary brain surgery with inevitable risks.

To neuroscientists, the most intriguing development shown Friday may have been what Musk called “the link,” a silver-dollar-sized disk containing computer chips, which compresses and then wirelessly transmits signals recorded from the electrodes. The link is about as thick as the human skull, and Musk said it could plop neatly onto the surface of the brain through a drill hole that could then be sealed with superglue.

“I could have a Neuralink right now and you wouldn’t know it,” Musk said.

The link can be charged wirelessly via an induction coil, and Musk suggested that people in the future would plug in before they go to sleep to power up their implants. He thinks an implant also needs to be easy to install and remove, so that people can get new ones as technology improves. You wouldn’t want to be stuck with version 1.0 of a brain implant forever. Outdated neural hardware left behind in people’s bodies is a real problem already encountered by research subjects.

The implant Neuralink is testing on its pigs has 1,000 channels and is likely to read from a similar number of neurons. Musk says his goal to increase that by a factor of “100, then 1,000, then, 10,000” to read more completely from the brain.

Such exponential goals for the technology don’t necessarily address specific medical needs. Although Musk claims implants “could solve paralysis, blindness, hearing,” as often what is missing isn’t 10 times as many electrodes, but scientific knowledge about what electrochemical imbalance creates, say, depression in the first place.

Despite the long list of medical applications Musk presented, Neuralink didn’t show it’s ready to commit to any one of them. During the event, the company did not disclose plans to start a clinical trial, a surprise to those who believed that would be its next logical step.

A neurosurgeon who works with the company, Matthew MacDougall, did say the company was considering trying the implant on paralyzed people—for instance, to allow them to type on a computer, or form words. Musk went further: “I think long-term you can restore someone full body motion.”

It is unclear how serious the company is about treating disease at all. Musk continually drifted away from medicine and back to a much more futuristic “general population device,” which he called the company’s “overall” aim. He believes that people should connect directly to computers in order to keep pace with artificial intelligence.

“On a species level, it’s important to figure out how we coexist with advanced AI, achieving some AI symbiosis,” he said, “such that the future of world is controlled by the combined will of the people of the earth. That might be the most important thing that a device like this achieves.”

How brain implants would bring about such a collective world electronic mind, Musk did not say. Maybe in the next update.

Deep Dive

Humans and technology

Building a more reliable supply chain

Rapidly advancing technologies are building the modern supply chain, making transparent, collaborative, and data-driven systems a reality.

Building a data-driven health-care ecosystem

Harnessing data to improve the equity, affordability, and quality of the health care system.

Let’s not make the same mistakes with AI that we made with social media

Social media’s unregulated evolution over the past decade holds a lot of lessons that apply directly to AI companies and technologies.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.