The Minecraft Institvte of Technology

It started, as many things do, with a bunch of bored college kids. With covid-19 beginning to spread in the US, we’d been sent away from campus a week before spring break, in a mass move-out event we came to call MITExit, the TechXodus, or simply Hell Week. Most of the undergraduate student body was scattered to various corners of the earth and at loose ends for the two weeks before virtual learning would begin. Eager to stay connected online, many of us found our way to the Busy Beaver Discord server, a chat and gaming platform set up for displaced members of the MIT community. We were itching to do something—anything.

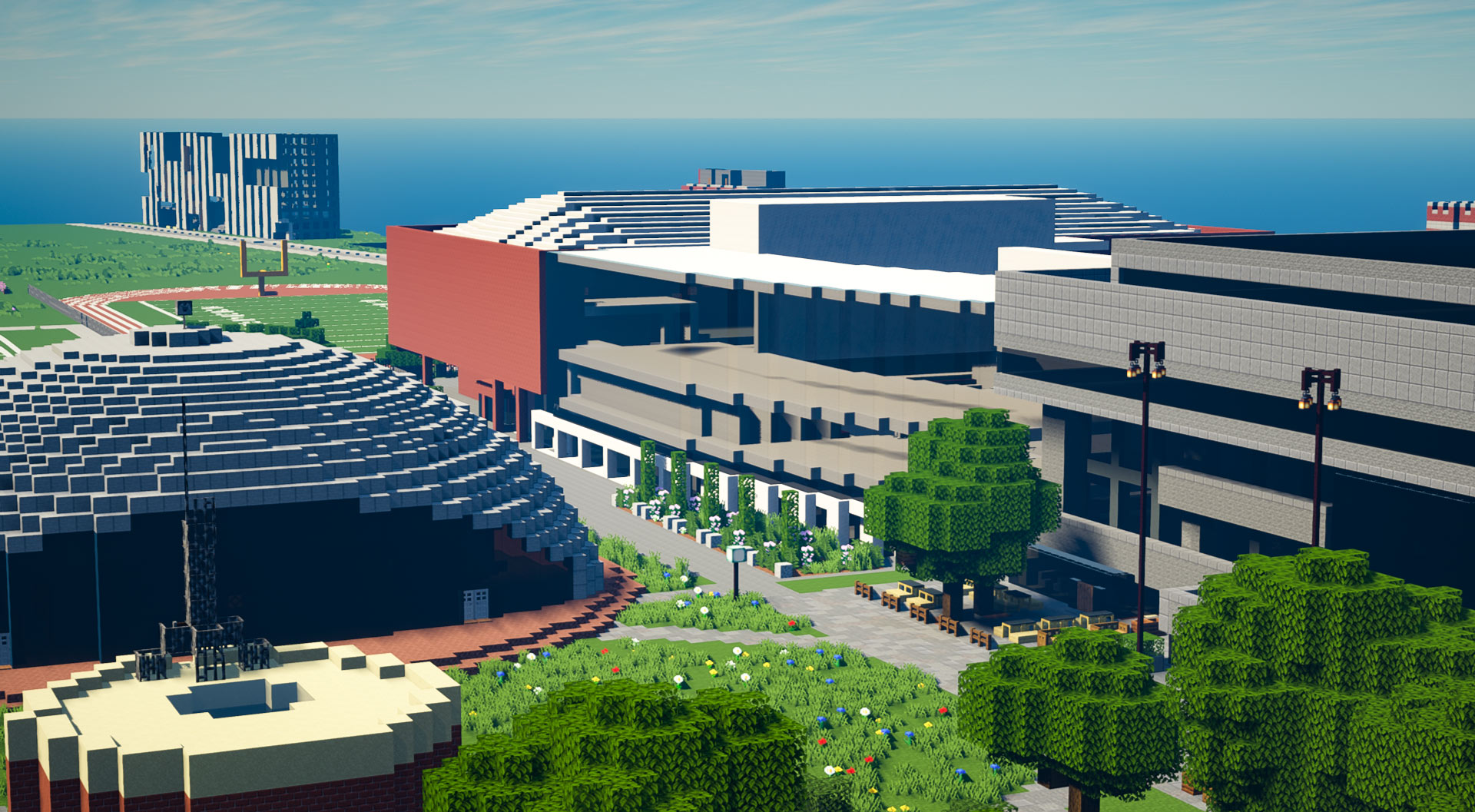

Sparked by some chatter about building a virtual campus away from campus, Jeffery Yu ’22 turned to the world-building game Minecraft. It can be used much like a digital Lego set that lets users arrange blocks and building materials in a virtual environment. Yu, a math major, initialized the MIT Minecraft server on an old computer at home, and Alex Patton ’20, a mechanical engineering major, got to work laying down building foundations by converting a map to plots. Electrical engineering and computer science PhD student Billy Moses ’18 and the Student Information Processing Board—a volunteer group that has been contributing to MIT’s computing environment since 1969—stepped in to help host the MIT Minecraft server on a physical server in the SIPB office. Student builders started a spreadsheet to track progress on buildings. We created a dedicated discussion chatroom in Discord, and soon we began referring to the MIT Minecraft project as the Minecraft Institvte of Technology.

While planning our virtual re-creation of campus, we agreed to use a scale close to 1:1, meaning that most blocks would be equal to one meter. Making sure everyone used the same ratio let us crowdsource the 3D modeling of a virtual MIT campus that, while endearingly low-resolution, would be sized to scale.

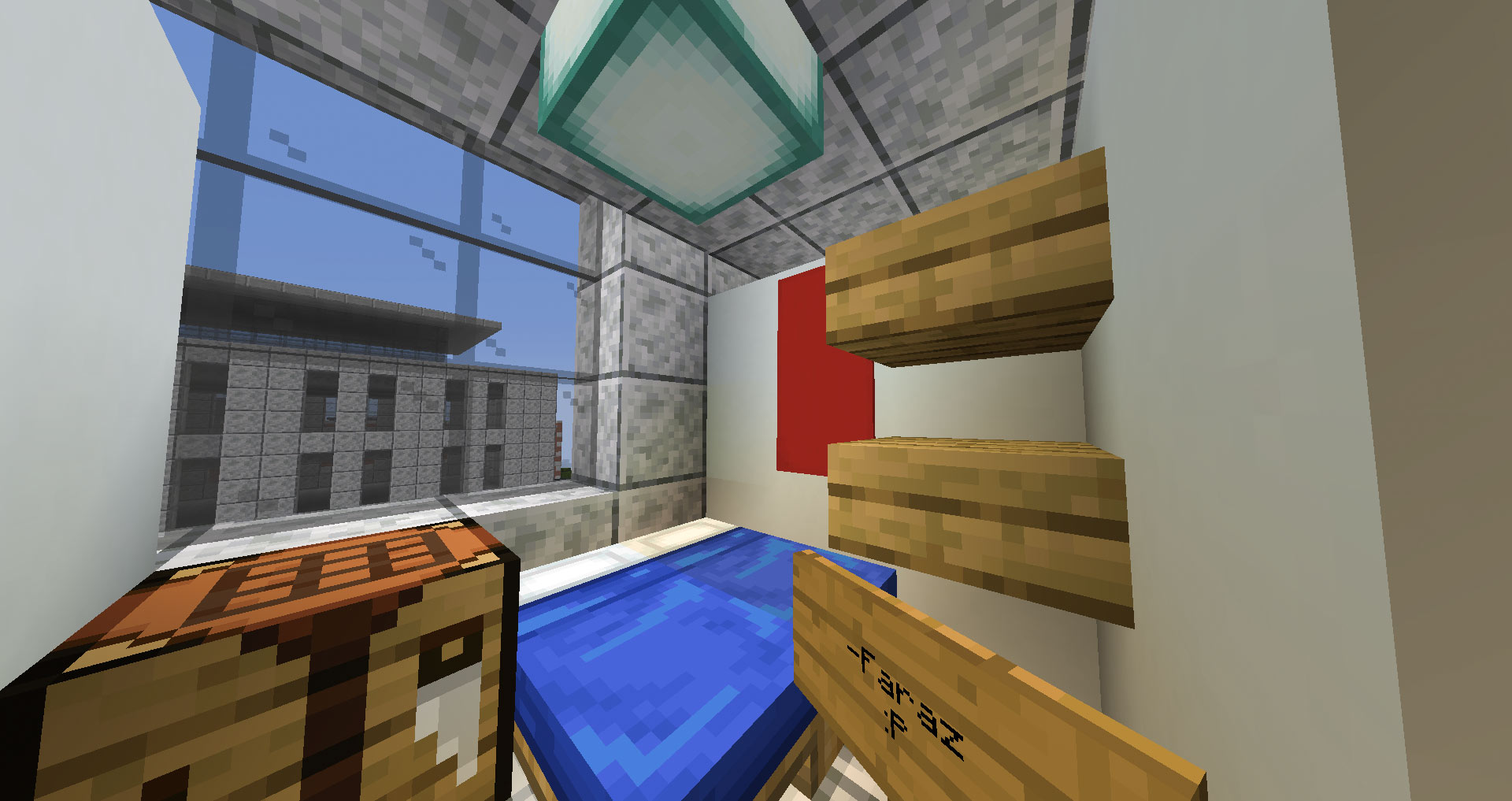

As Beavers, we do our best work by night. So every day when I logged in, I found that something new had popped up or changed as students re-created buildings from memory, aided by reference photos, floor plans, and Google Earth estimates. The first building to go up was Kresge Auditorium. But the undergraduate dorms quickly followed, often with detailed interiors. Then fraternities, sororities, and independent living groups joined in to build their living communities.

The night before we recorded a video about the project for the News Office website, I helped to ensure that the iconic Great Dome and Killian Court were created. I had taken pictures of the printing plates used to produce the original plans for the dome when I’d seen them on display between Lobbies 10 and 13 during my Campus Preview Weekend (CPW) in 2019. Using these photos as a reference, we constructed a to-scale version of the dome. The architects are likely rolling in their graves at this use of their plans, but our attention to detail allowed the producers of the virtual commencement video to transition seamlessly from the animated dome to images of the real one.

Scattered though we were, over 250 builders worked to construct the virtual version of MIT. Together we created a user-populated map of the campus places that felt important, whether living communities, academic spaces, or recreation facilities. The result provides a snapshot of campus as it was when the world went on pause in March. And the virtual campus gave those of us who helped build it a chance to reflect on what the real campus means to us. Our creation is full of inside jokes based on details only an MIT person would know. For example, the Unified Lounge in Building 33 includes machining equipment and non-player characters labeled Todd and Dave, in honor of two technical instructors well known to aero-astro students. The Simmons Hall ball pit includes a bouncy floor. The Banana Lounge in Building 26 has chests full of free fruit, and a colorful piano outside. And in a nod to the Purell hand sanitizer stands that dotted campus in March, dispensers on the virtual campus offer healing potions.

Given that most of us working on this have a background in computing rather than e-sports or gaming, we put a lot of thought into the computing structure and developed new features for the Minecraft server. Proximity-based voice chat allows users within close range of each other on the server to talk to each other, almost the way we had passing conversations in the halls of MIT. Knowing the significance of murals to living communities, someone developed a script tool that allows 128x128-pixel images to be stored on a map object that can be placed on the side of a block. Working on the project was like a peer-taught crash course in server management and maintenance.

The virtual campus gave those of us who helped build it a chance to reflect on what the real campus means to us.

Building and managing a virtual community modeled after a real physical space also taught us a thing or two about human dynamics. MIT’s open-campus policy allows tourists to pass through the Infinite and some buildings, which led us to adopt an unregulated access policy at first. Then came what the online community calls “griefers”—two users who destroyed other people’s creations on the server just to cause trouble. Thanks to our rigorous hourly backup process, our moderators were able to erase the damage and restore the campus quickly. But this incident led us to restrict building permission to verified MIT community members and alumni.

The virtual campus has had plenty of visitors. The incoming Class of 2024 was invited to take a peek during virtual CPW, when a few tour guides led virtual campus tours from their homes; dorms like Next House and Simmons were eager to show off their digitally reconstructed spaces, and a fraternity asked for a copy of the map to host a game of capture the flag with the ’24s. The MIT Logarhythms produced “MineLogs,” a virtual a cappella concert that included skits featuring their Minecraft avatars. The Burton-Conner Bombers threw their annual DTYD (Dance ’Til You Drop) party in MIT Minecraft, with music patched in through proximity voice chat. And a Tech Reunions webinar gave alumni a chance to check out the virtual campus.

It’s hard to judge when our construction will be done, if ever. For now, we’re classifying it as a living project and welcoming spin-offs. Going forward, we might be able to use MIT Minecraft to digitally resurrect the MIT of decades past. We can create copies of our current server, reach out to alumni, and work with historical records to re-create what campus buildings looked like in earlier times. Virtual visitors might one day be able to track MIT’s evolution through history by walking through these different versions of MIT Minecraft. Or perhaps we could add toggle switches to make famous hacks visible on the map. And what about an alternate universe where Bexley and Senior House exist in the present day? Maybe we could even test out designs for a new Student Center in the context of our virtual campus. Once we’ve built the Minecraft MIT campus we have, we can create the virtual campus we want.

Amanda Shayna Ahteck ’23 has been working on MIT Minecraft at home in Holmdel, New Jersey. Direct inquiries about MIT Minecraft to the project’s moderators at sipb-minecraft-root@mit.edu.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.