These are the closest images of the sun ever taken

It’s been a banner year for solar observations so far. The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii presented some of the best images ever taken of the sun, showing us a caramel-like surface where individual cells of plasma ooze up and down hypnotically. Not to be outdone, the ESA-led Solar Orbiter mission has just released its own first images of the sun. Though perhaps not as surprising as DKIST’s, they are nonetheless the closest images of the sun ever taken, from just over 47 million miles away (about half the distance from Earth to the sun).

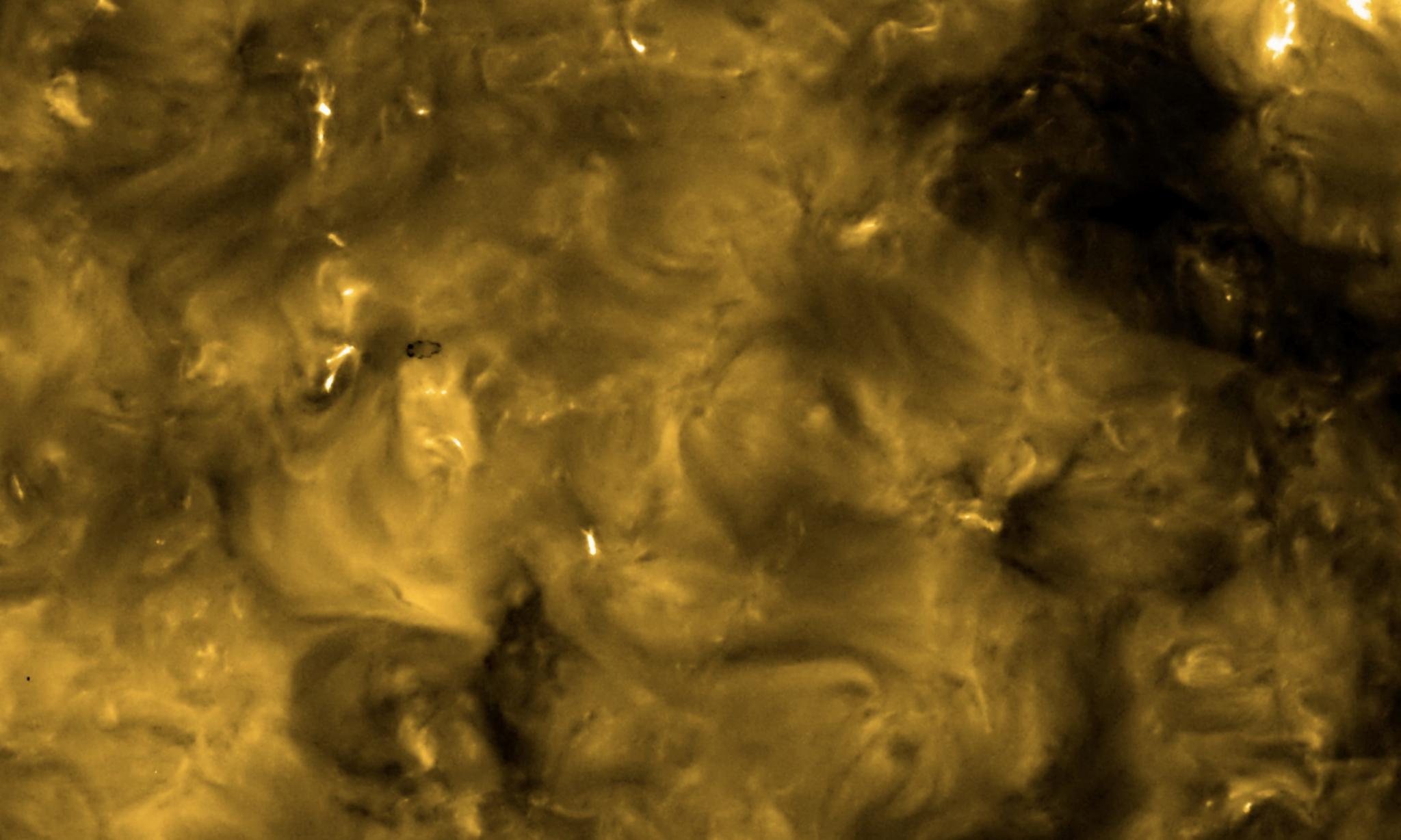

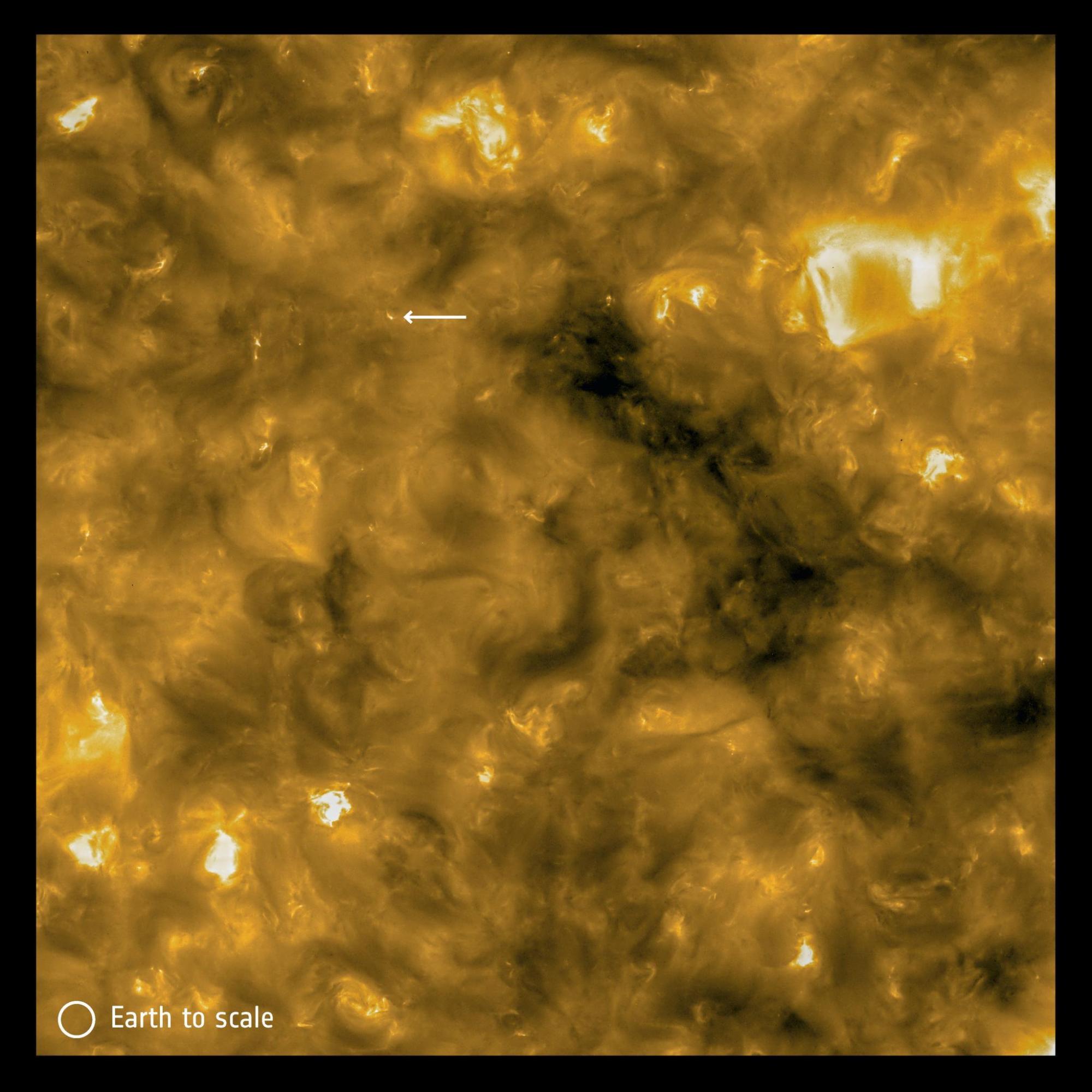

The new images show a landscape of constant stormy activity emanating from the sun’s corona (atmosphere), revealing features that are just 250 to 310 miles across. In particular, the images reveal the existence of miniature, “campfire”-like solar flares near the surface. “We haven’t been able to properly see them before, so it’s really exciting,” says David Long, a principal investigator for the mission’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager instrument (EUI).

One of the most pressing questions that has always confounded scientists is the coronal heating problem: why the sun’s atmosphere (over 1 million °C) is so much hotter than its surface (about 5,500 °C).

The new observations suggest the heating might be caused by numerous small events happening all over (i.e., the campfires), all releasing energy that torches the corona and collectively raise the atmospheric temperatures.

More data will be required to prove this is how corona heating works, “but it’s a very promising first set of observations,” says Long.

Solar Orbiter was launched on February 10. It is fitted with 10 different instruments, including six telescopes that peer directly at the sun and measure it across several different wavelengths, and four instruments that monitor the environment around the spacecraft (like the distribution of solar winds and the structure of magnetic field lines). The EUI was responsible for snapping the high-resolution ones that show the campfires, but the other instruments show the sun through those other lenses.

The new data comes from the mission’s first close pass of the sun back in June. In early 2022, the spacecraft will get to just under 30 million miles away from the sun—closer than even Mercury’s orbit.

Besides just teaching us more about the sun’s physical properties, there’s a more practical reason behind the Solar Orbiter: understanding space weather, or the stream of charged particles energized by the sun and propelled into the rest of outer space. Earth’s magnetic field protects the planet from these particles, but extreme space weather can fry any electronic equipment in orbit (such as critical satellites used for GPS and communications) or the electrical grids on the surface that power our everyday lives.

Learning how to anticipate nasty space weather events so we can protect ourselves means we need to know more about how the sun’s magnetic fields interact with its active regions to give rise to solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and extreme bouts of solar wind.

Solar Orbiter is far from the only tool being used to study the sun, but it fills a niche others can’t. Ground-based observatories like DKIST cannot observe the sun in UV and x-ray spectra very well because of Earth’s atmosphere. And while NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will get closer to the sun, it will in fact be too close for cameras to directly image the sun in a useful way.

For the moment, the spacecraft is in its cruise phase and moving farther away from Earth and behind the sun, so its telescopes won’t be able to study these campfire features until the start of the science phase in November 2021 (its four instruments are already in routine operations). But this is nevertheless a good time to be observing the sun. The new solar cycle has either just begun or will begin later this year; either way, the sun is revving up for a new period of activity. New solar eruptions will be taking place, and the data collected by the Solar Orbiter will tell us more about how these eruptions happen, how they lead to space weather events that could have a severe impact on human activity, and how we could predict them ahead of time. “This is really where Solar Orbiter is going to give us some amazing results,” says Long. “It’s really early days, but these pictures really give us a stunning first look, and I can’t wait until November next year when we can start making regular scientific observations.”

Deep Dive

Space

The search for extraterrestrial life is targeting Jupiter’s icy moon Europa

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will travel to one of Jupiter's largest moons to look for evidence of conditions that could support life.

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.