Will astronauts ever visit gas giants like Jupiter?

Every week, the readers of our space newsletter, The Airlock, send in their questions for space reporter Neel V. Patel to answer. This week: Can we go to Jupiter?

Once we move past the asteroid belt, is it realistic to assume there is a chance humans could ever explore any of the gas giants, like Jupiter, really close to its atmosphere? And what that would look like? —Sarah

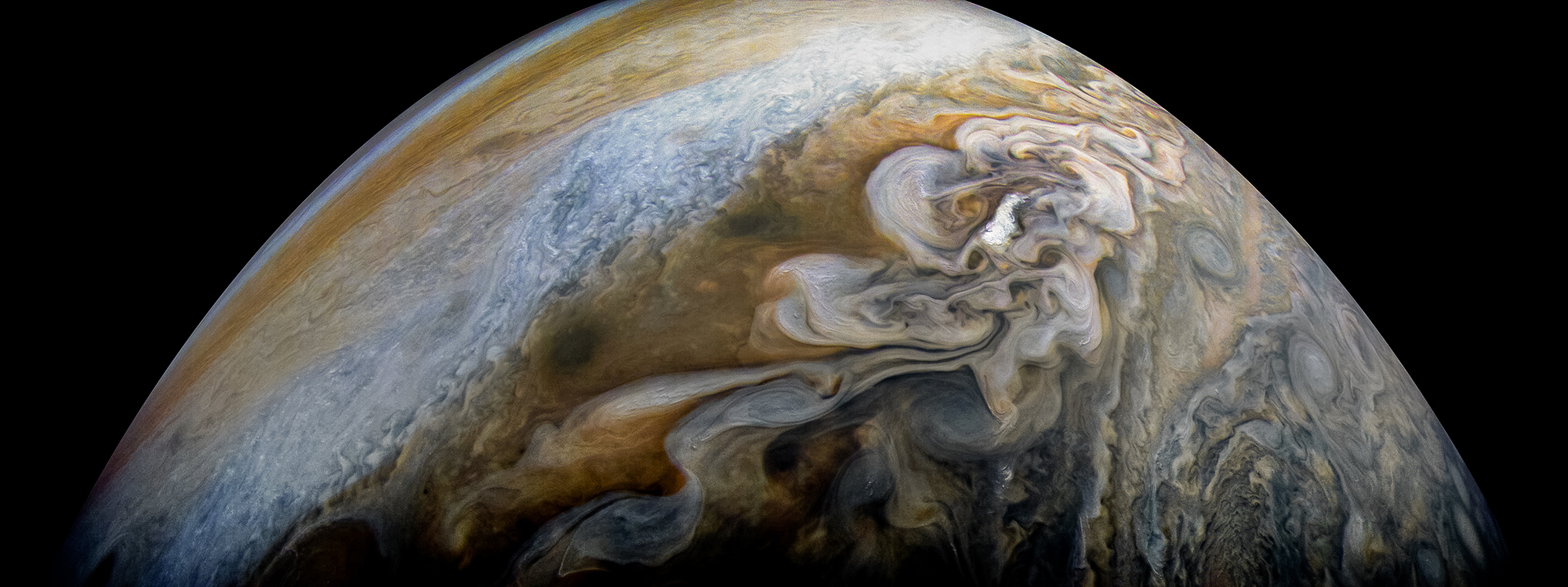

Jupiter, like the other gas giants, doesn’t have a rocky surface, but that doesn’t mean it’s just a massive cloud floating through the vacuum of space. It’s made up of mostly helium and hydrogen, and as you move from the outer layers of the atmosphere toward the deeper parts, that gas grows denser and the pressures become more extreme. Temperatures quickly rise. In 1995, NASA’s Galileo mission sent a probe into Jupiter’s atmosphere; it broke up at about 75 miles in depth. Pressures here are over 100 times more intense than anything on Earth. At the innermost layers of Jupiter that are 13,000 miles deep, the pressure is 2 million times stronger than what’s experienced at sea level on Earth, and temperatures are hotter than the sun’s surface.

So clearly, no human is going to be able to venture too far down into Jupiter’s depths. But would it be safe to simply orbit the planet? Perhaps we could establish an orbital space station, right?

Well, there’s another big problem when it comes to Jupiter: radiation. The biggest planet in the solar system also boasts its most powerful magnetosphere. These magnetic fields charge up particles in the vicinity, accelerating them to extreme speeds that can fry a spacecraft’s electronics in moments. Spaceflight engineers have to figure out an orbit and spacecraft design that will reduce the exposure to this radiation. NASA figured this out with the triple-arrayed, perpetually spinning Juno spacecraft, but it doesn’t look as if this would be a feasible design for a human spacecraft.

Instead, for a crewed spacecraft to safely orbit or fly past Jupiter, it would have to keep a pretty significant distance away from the planet.

Not every gas giant in the solar system is like this, but they all also come with various other problems that would make it difficult for humans to visit up close. Neptune, for instance, has the strongest winds in the solar system, reaching speeds of up 1,100 miles per hour. Both Neptune and Uranus are “ice giants” that have elements and compounds heavier than helium and hydrogen, like methane and ammonia. These denser materials could make it even harder for a spacecraft to plunge into these atmospheres, since the spacecraft would be damaged sooner. Saturn’s own magnetosphere is smaller than Jupiter’s but still 578 times more powerful than Earth’s, so radiation would still be a huge issue to contend with.

For the time being, until we find out how to build a spacecraft using materials that could guard human astronauts from all these elements, any up-close exploration of the gas giants will have to be through robotic spacecraft.

Deep Dive

Space

The search for extraterrestrial life is targeting Jupiter’s icy moon Europa

NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will travel to one of Jupiter's largest moons to look for evidence of conditions that could support life.

How to safely watch and photograph the total solar eclipse

The solar eclipse this Monday, April 8, will be visible to millions. Here’s how to make the most of your experience.

How scientists are using quantum squeezing to push the limits of their sensors

Fuzziness may rule the quantum realm, but it can be manipulated to our advantage.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.