3.024: Electronic, Optical, and Magnetic Properties of Materials

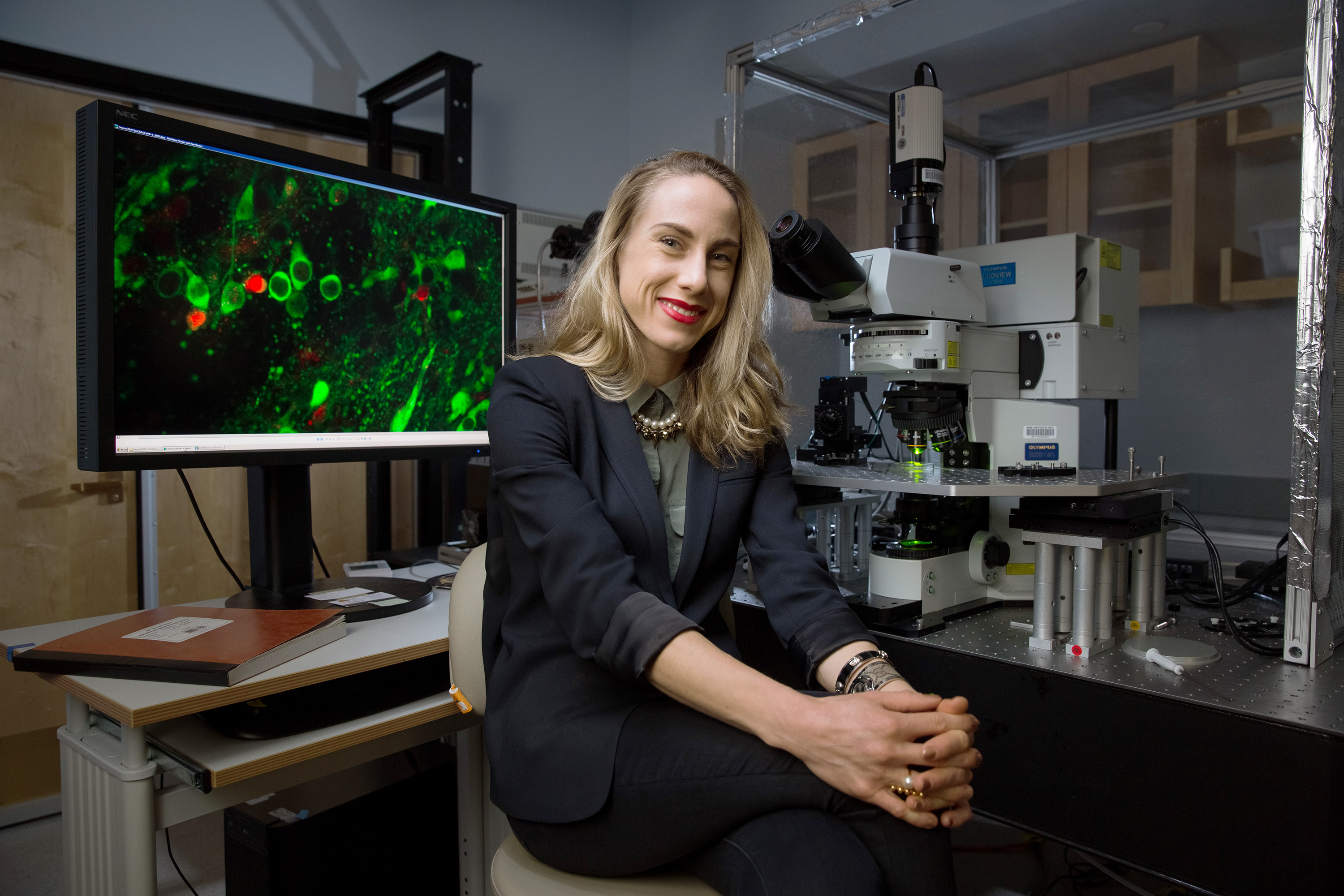

Polina Anikeeva, associate professor of materials science and engineering, normally takes what she calls an old-school approach to teaching 3.024 (Electronic, Optical and Magnetic Properties of Materials): lectures at the blackboard, lots of discussion, office hours. But a few years ago, after the department decided to create online versions of all its core courses, she’d worked with the Office of Digital Learning to develop an MITx version. So when she and her teaching team learned that students would not be coming back after spring break, they figured that the class could easily be shifted online.

“The team and I thought, okay, it’s straightforward,” she told the ACWG in one of the 8 a.m. Zoom calls. “We have these beautiful materials, we have all the p-sets, we have all the projects planned out. All we have to do is meet with students and answer questions.”

But when the class met on Zoom to discuss the lectures they’d been asked to watch, it became apparent that none of the students had done so. No one wanted to talk, so she dove into her lecture using the whiteboard function on Zoom. The same thing happened the next time the class met, and the next. She polled the class and found that more than half the students actually preferred the live Zoom lectures.

“The overwhelming majority wanted to have their instructor awkwardly lecture in real time rather than watch the beautifully recorded resources we were so proud of,” Anikeeva reported. While the students appreciated being able to go back and watch the MITx lectures, what they valued most was “this ephemeral feeling that I’m lecturing just for them, not to the 2016 classroom,” she said. “They want their own experience that is ultimately created for them, and they’re willing to sacrifice the quality just to watch that immediateness.”

The trick, says Krishna Rajagopal, MIT’s dean of digital learning, is to blend the asynchronous and the synchronous: use great asynchronous material if you have it, but remember that students want the synchronous experience too.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.