A professor’s “new normal” is anything but

Since the covid-19 pandemic took hold in the US, most of us stuck at home have found that all the days seem the same. For Elazer R. Edelman ’78, SM ’79, PhD ’84, every day is completely different—but all of them are long.

As the director of the MIT Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES), Edelman has been tapped to direct the MIT Medical Outreach and Crisis Management Team. Initially the cross-campus group formed to collect donations of extra personal protective equipment (PPE) from around the Institute and distribute them to health-care workers at hospitals, medical centers, and nursing homes in need. But soon the group also took on the task of marshaling MIT resources to develop and manufacture items like disposable face shields and perhaps even to develop a remote stethoscope. By May, the team was also contributing PPE to underserved populations and preparing to protect MIT community members with such gear when the campus ramps back up.

As a senior attending physician in the cardiac intensive care unit at Brigham and Women’s in Boston, he has been stepping up his time at the hospital, working closely with his colleagues to treat critically ill covid-19 patients, many of whom are in cardiac and respiratory distress. And as a professor of medical engineering and science at MIT, and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he—like teachers across the globe—is grappling with the switch to online instruction and holding frequent virtual meetings with his students.

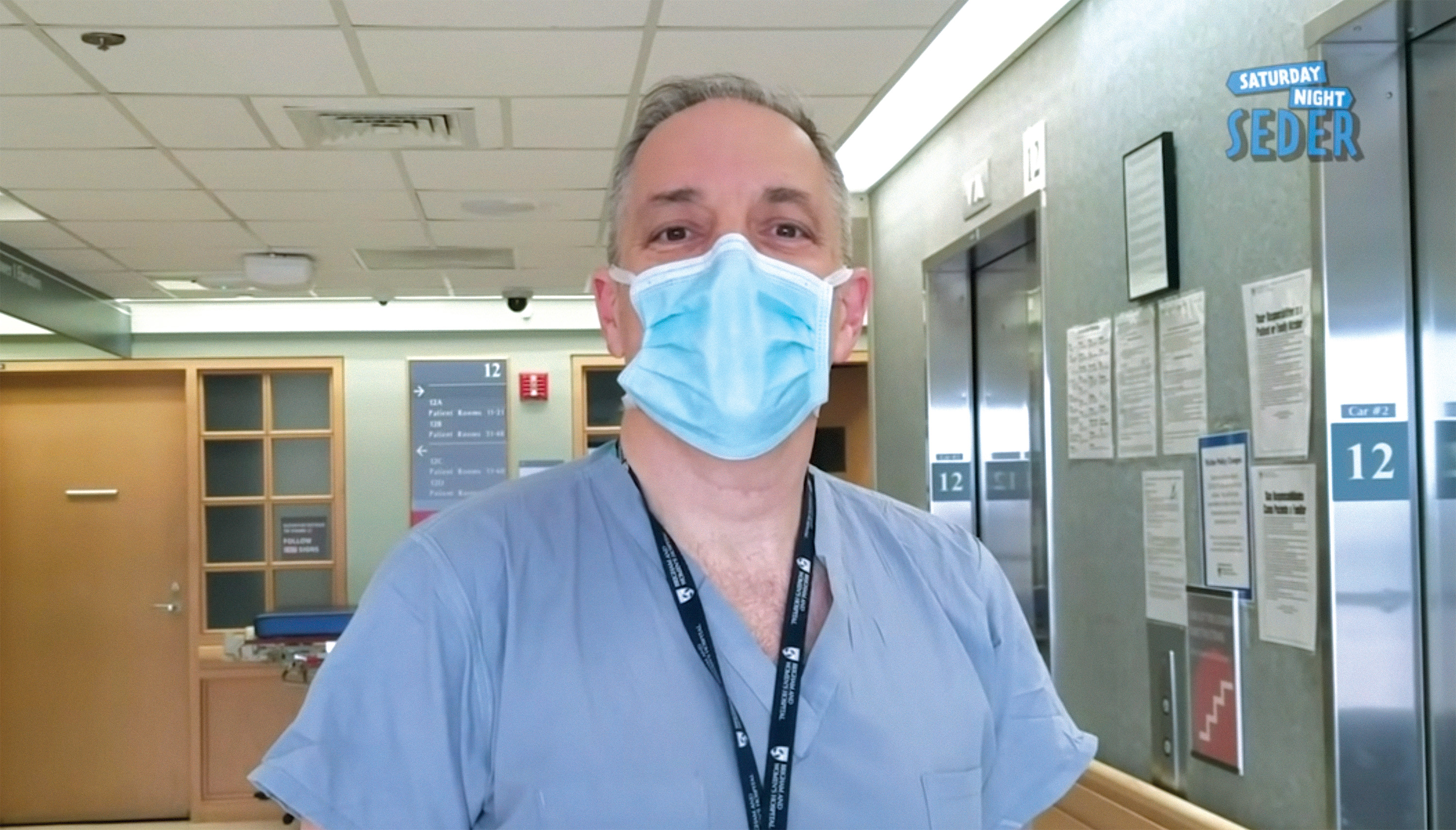

In early April, he also found time to make a cameo appearance on “Saturday Night Seder”—a streamed event described by the New York Times as “part variety show, fundraiser, and theatrical experience” and featuring such celebrities as Jason Alexander, Sarah Silverman, and Bette Midler. (The comedian and writer Alex Edelman, one of his three sons, was the head writer for the show, which raised more than $3 million for the Coronavirus Emergency Response Fund of the CDC Foundation, a nonprofit that supports the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) The day after that aired, he and MIT mechanical engineering professor Martin Culpepper, SM ’97, PhD ’00, were jointly interviewed for NBC News about their collaboration to design disposable face shields that can be mass-produced quickly for hospitals nationwide (see “Protection on the cheap”).

“MIT has taught me not only to multi-task, but also how to use technology as a means to continue to embrace community,” Edelman says. In fact, while he’s saddened by the new pandemic reality, he says it’s been magical to see how the MIT community has risen to the challenge. He marvels at what he calls “the unprecedented collaboration taking place at MIT across all departments and roles—and with other academic institutions and medical centers—as the race to find an effective response to the pandemic continues.” During a campus-wide town hall meeting on Zoom in April, President L. Rafael Reif paraphrased a comment Edelman had made in a call as the pandemic dawned: “You said in that meeting, Elazer, this is what we are made to do. This is what our community was created for: to harness science and engineering and technology to improve the human condition.” And that, Reif added “is what everybody tries to do at MIT every day.”

While all routines are out the window for Edelman during the covid-19 crisis, his schedule for an MIT day might go like this: Waking before 6 a.m., he prepares for an onslaught of calls and emails before an early morning call with MIT leadership and faculty and researchers from all departments, who share their research updates and the challenges of managing a campus remotely. Then the day officially begins with online lecture and lab sessions for his graduate course on quantitative physiology of the cardiovascular system, followed by online student conferences, lab groups, and team meetings. He also spends a lot of time on emails or phone calls with MIT or hospital colleagues about covid-19 response efforts. And in between, he fits in running IMES, MIT’s hub for health science research, innovation, and education. Evening is for family, and often a late-night Zoom call such as a recent one with a group of alumni based in China, which is looking for ways to support the MIT efforts. When Edelman and Culpepper were first working on the face shield designs in March, the two often communicated into the early morning hours. “My calendar is a series of overlapping Zoom meetings and phone calls, interrupted by messages all characterized as urgent,” he says.

On days when he is leading the cardiac ICU team, there is even less “normal,” as everything else takes a back seat to patients’ life-and-death needs. “Attending in the ICU has always been a full-time affair. No night, no day—24 hours of concern,” he says. “With covid, we now must reinvent how we deliver care to the most vulnerable as well as protect the community, and this adds even greater challenge and responsibility.”

More efforts to meet the challenge have come from all corners of the MIT campus, Edelman says. It’s not just the faculty, researchers, and labs feverishly working on solutions; it’s also the facilities and procurement departments and the campus services team, in the mailroom and elsewhere, whom he calls “dominant partners” in all the projects under way. The PPE effort, for instance, involved more than 50 MIT departments, labs, and centers donating more than 543,000 vital pieces—including N95 masks, surgical masks, goggles, and swabs—to hospitals, clinics, medical centers, and municipal services such as the police and fire departments in Boston and Cambridge. “It is indeed amazing to see the impact of such wonderful people,” Edelman says. “I am so proud to be a member of this magnificent community.”

Even though he says he has never been so busy as he is now, he is also grateful for the increased time that physical distancing has let him spend with his family. “I get to spend more time with my father; I have greater connectivity with my brothers and with their families,” Edelman says. “I have seen much more of my wife and my children than I ever did before.” (His wife, Cheryl, and middle son, AJ, also happen to be MIT alumni, and his youngest, Austin, an MIT sophomore, returned home in March to finish the semester.) And in some ways, the quality of the time he spends with his students has increased as well. Before, he says, it was enough for them to know that he was in his office and for him to know that they were in the lab. Now that it takes a dedicated effort to meet, they are meeting more often, albeit virtually. Spontaneity may be limited, but their interaction is still satisfying and the quality of work hasn’t suffered.

And Edelman’s long days are unlikely to grow much shorter anytime soon.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.