The 1918 flu at MIT

The 1918 influenza epidemic, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, hit the US in three devastating waves. But its arrival at MIT ranks as little more than a footnote in the Institute’s archives, overshadowed by the urgency of training soldiers for the Great War.

As the start of the 1918–19 academic year approached, it was anything but business as usual at the Institute. The US had been at war since April 1917, and MIT’s president, Richard Maclaurin, felt strongly that “academic institutions, particularly those with strong science and engineering programs, must play a central role in national defense.” In late 1917, the faculty had decided to support the war effort by running courses almost continuously throughout the year, temporarily omitting those less important for war.

In July 1918, Maclaurin was appointed by the US secretary of war as educational director of the new Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Established by the government in early 1918, the SATC was similar to the ROTC, offering those volunteering for military service an opportunity to get a college education as they trained. Maclaurin’s responsibilities included choosing locations for units, selecting courses, and managing the organization nationwide.

But when the War Department decided in early September that it wanted to have five million troops in Europe by the summer of 1919, Maclaurin had to swiftly reorganize the SATC into what amounted to a series of mobilization camps. A month later, these camps were starting up all over the country. As the program grappled with the influenza epidemic, the difficulties of housing and feeding the men, and the need for entirely new schedules of instruction, all final decisions—which affected 524 institutions and 150,000 men—rested with Maclaurin.

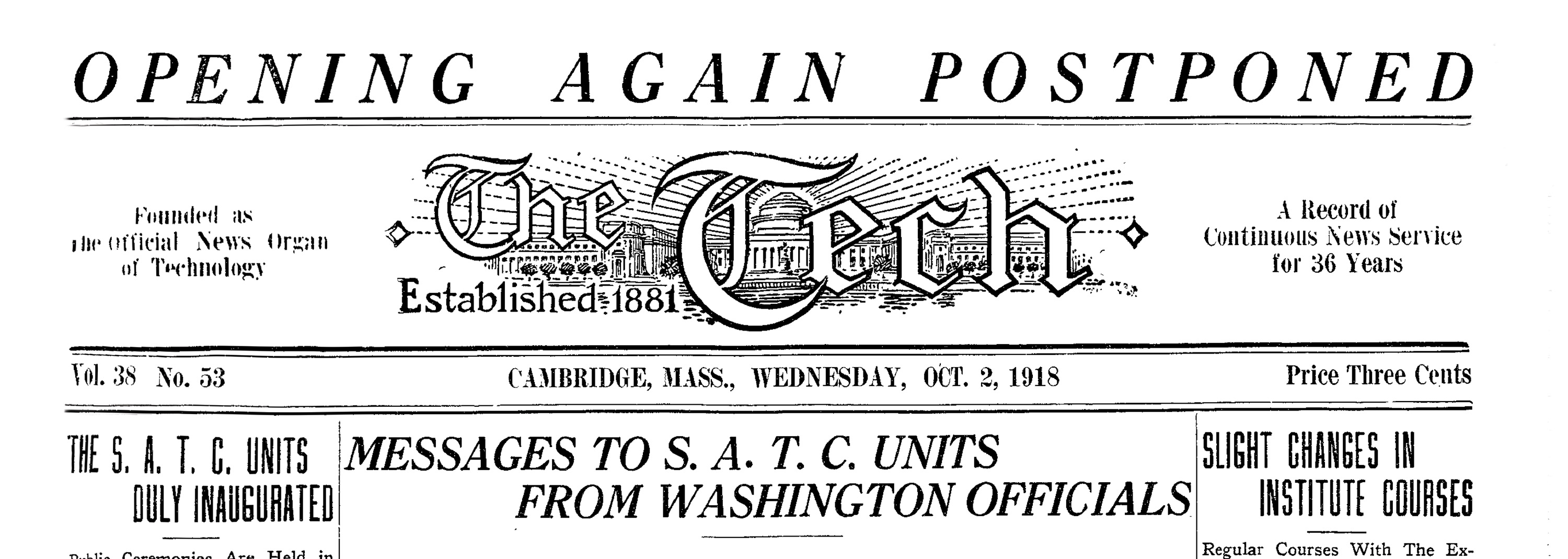

Just as MIT was finalizing the construction of five SATC barracks and a mess hall meant to accommodate “a thousand men at a sitting,” as The Tech reported, the flu hit Boston. At the request of local and federal authorities, MIT postponed the start of the academic year by three weeks. To avoid large gatherings of people, the planned October 1 SATC induction ceremony was pushed to October 11 and the opening of the mess hall was delayed. “It is the wish of the Registrar and his colleagues that all students keep away from the Institute until further notice. Students living east of New York City are requested to leave immediately for their homes,” read an October 2 notice in The Tech. “The offices of all the Faculty are to be closed, and only those who are on absolutely important business will be admitted to the Institute. It is our aim to aid in every possible way the fight against this terrible disease which now seems to have passed its crisis. Institute men, do your part. Make this extra time count. It will be some time before we get another vacation.”

The “terrible disease” would not leave the Institute unscathed. On October 12, The Tech began reporting the deaths from pneumonia or influenza of alumni in the military. November 6 marked the first mention of illness on campus, with a notice of the deaths of two SATC students.

Word of the impending armistice reached MIT a few days later. The November 9 issue of The Tech reporting that news also included a little more detail about the extent of the influenza epidemic on campus. An article about the use of the Phi Beta Epsilon fraternity house as the SATC infirmary said that “at present there are forty-five on the sick list. During the recent epidemic, eighty-three patients were taken care of.” Only two had died.

With the war suddenly over, the need for the SATC evaporated, and MIT returned to training scientist and engineers. After a fall in which, as The Tech noted, there was “no college spirit or college life,” social and athletic clubs began starting up in December. By year’s end, the epidemic had claimed the lives of at least three more students and an instructor. But the toll it had taken on the Institute had gone largely unrecorded.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.