Why some covid-19 tests in the US take more than a week

Jason Bae, an urgent-care physician in Northern California, has been seeing covid-19 patients for almost a month. When he first started ordering coronavirus tests, around the week of March 9, his health-care system was quoting a 48- to 72-hour turnaround time from their third-party laboratory. But “even from the very beginning, a lot of tests would take five to six to seven days to come back,” he says.

Around that time, Bae developed a sore throat after being exposed to a patient who had tested positive. He self-isolated, stayed home from work, and got his covid-19 test through the Stanford Health system, which is separate from his employer’s health system. Stanford had built a testing facility in house, and the result came back in less than three days: negative.

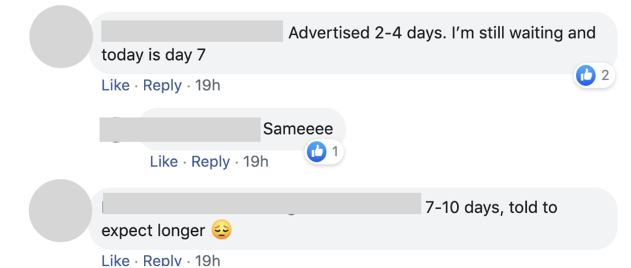

When he went back to work, Bae found that test results were coming back even more slowly than before, with many taking over a week. So on March 22, he posted in a private Facebook group of physicians to ask what his colleagues around the US were experiencing. The post drew over 1,500 replies. More than 40% indicated a turnaround time of seven days or longer.

Testing remains among the most pressing problems with America’s response to the pandemic. On March 31, the country announced that it has collectively tested a million people—weeks behind the schedule repeatedly promised by the Trump administration.

That is more than a mere statistic: testing people is the key to understanding how widely the novel coronavirus has spread and gauging its severity. Health-care workers need access to quick testing so that they can continue to safely take care of the rest of us. In the near future, we will also need testing to figure out how many among us may be immune and can get out of our houses and restart the economy.

More on coronavirus

Our most essential coverage of covid-19 is free, including:

How does the coronavirus work?

What are the potential treatments?

What's the right way to do social distancing?

Other frequently asked questions about coronavirus

---

Newsletter: Coronavirus Tech Report

Zoom show: Radio Corona

See also:

Please click here to subscribe and support our non-profit journalism.

But as more and more Americans have been swabbed to test for covid-19, the lag between sample collection and the delivery of results is unpredictable. As the responses to Bae’s post show, some labs are handling the rise in demand worse than others.

In the responses, Bae found two distinct patterns. “The outpatient testing through the commercial labs is getting longer and longer,” he says, “whereas with the inpatient testing for hospitalized patients, the turnaround time has been coming down.”

In an effort to help understand the situation, Bae collected the responses in a spreadsheet. Analysis of his data reveals a patchwork system drowning in demand, but with some clear, fixable problems and signs of hope.

Who is doing testing?

There are currently four main types of labs performing coronavirus testing:

- the federally run Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which initially handled all US testing (and was widely seen as a bottleneck early on in the outbreak)

- public health labs run by states

- in-house hospital labs that are part of a broader health system

- commercial labs, such as ARUP, BioReference Laboratories, LabCorp, Mayo Clinic Laboratories, Quest Diagnostics, and Sonic Healthcare, which now account for the bulk of testing volume throughout the country

While there currently isn’t any aggregate data on the number of in-house hospital tests done in the US to date, it’s likely a small percentage of the total. In Massachusetts, where there are many big academic hospitals, about 19% of all covid-19 tests completed have been done at in-house labs, while 65% have been performed at a commercial lab, according to figures published by the state’s health department. In most states, that figure is almost certainly much lower, as only the largest and best-appointed hospitals tend to have the resources to set up their own testing facilities.

What’s going on with delays at commercial labs?

There are three major reasons for the delays. The first is a shortage of supplies. When a commercial lab conducts a covid-19 test, the lab first supplies materials like nose or throat swabs to the testing locations. But according to the American Clinical Laboratory Association (ACLA), an industry group whose members include the big commercial testing companies, the supply of testing kits is still a problem, as is access to reagents, protective gear, and swabs. A shortage of any one item grinds the entire testing process to a halt. “No laboratory, in our understanding, has the predictable access to supplies necessary for the continued expansion of testing,” says ACLA president Julie Khani.

Health-care providers have little flexibility to change commercial lab providers quickly—contracts lock physicians’ offices into deals with individual labs, and labs can vary in their specifications for how samples are to be prepared. That makes it difficult to shunt demand from a backed-up lab to one with spare capacity.

The second problem is lack of funding. Despite promises from the federal government that people tested for covid-19 won’t be charged, there remains very little clarity on who will foot the bill for testing resources, Khani says, which makes it hard for labs to keep ramping up their capacity.

The third factor is poor prioritization of testing samples. Commercial labs have tried to deal with skyrocketing demand for tests by prioritizing the most urgent cases—but they rely on clinics and hospitals to sort patients’ tests according to CDC guidelines. If testing queues aren’t well managed, it slows down overall operations. In a letter sent to the CDC on April 2, the ACLA urged the agency to educate physicians and hospitals about testing prioritization.

In-house facilities have fast turnaround times but much smaller volume

California has been one of the hardest hit states in terms of testing delays. As of April 2, it had over 59,000 tests pending results, of about 95,000 conducted in total. (Two days later, however, it had reduced that backlog to 13,000.)

In-house testing offers several advantages over commercial labs, the most obvious being that test specimens don’t have to be packaged and sent back and forth between different facilities and systems. Processing, prioritizing, and tracking the tests all happens within one system, which cuts down on red tape and improves efficiency. They also have more flexibility in their testing workflows than large automated labs (Stanford has four different ways it can process a test, for example), which helps them react to fluctuations in supply.

Perhaps most important, in-house labs currently process only a fraction of the tests commercial labs handle. “It’s not surprising that if you’re trying to test for basically the whole country that isn’t affiliated with a medical system, your turnaround times may be slower,” says Ben Pinsky, the medical director of Stanford’s Clinical Virology Laboratory, which can now process up to 2,000 tests per day with an average turnaround time of under 24 hours. As of April 1, the lab had carried out about 10,000 of the 30,000 or so tests that had been completed in California.

Large manufacturing companies, like Roche, are starting to improve things further. They have recently begun selling testing devices that regional hospitals can use to test for covid-19 without having to send samples to an outside lab. With more hospitals and other facilities able to process tests on site, commercial labs might get some relief and begin to bring down wait times.

Pinsky is optimistic that it’s the start of a trend: “As all of these different tests become available, the availability of tests for patients will increase.”

What’s coming

The increased capacity can’t come soon enough. Bae says his few days in isolation were fairly painless—albeit hard for his wife, who had to care for their 10-month-old child, and a detriment to his clinic. But for others, it’s much more risky: sending an elderly or poor person into up to 14 of days isolation to wait for a result may not be feasible, or safe. Slow testing also means health-care workers who think they might have covid-19 are sidelined for longer.

For Bae, it’s changes on the ground that matter—and so far, he says he hasn’t seen many. “We hear these things like ‘This quick test is coming,’ or ‘All these things are being FDA-approved and fast-tracked,’” he says. But “with the exception of commercial testing being available, I really have not seen any of those things come true.”

If and when solutions come, they’re likely to be a mix of many different types of testing options at different facilities. In-house hospital labs, for example, are well-positioned to perform quick tests for the highest-priority people: health-care workers and gravely ill patients. But they need to be funded and staffed in order to scale, and smaller community hospitals need the support and training to implement newly manufactured testing systems.

Commercial labs have the potential to scale up even further than they have already, but they need clear pathways to funding from Congress, as well as redundancies that will guard against hiccups in the supply chain. And as more commercial labs start testing, taking their capacity into account when routing and prioritizing tests could also help reduce the backlog.

If the US can make the necessary changes to the network of laboratories involved in coronavirus testing, it might make these next six months a little less painful. To introduce true mass testing of the population, we need rapid, cheaper tests, like one offered by Abbott Labs that purports to deliver a result in five minutes. At-home testing would help even more. These advances might provide the volume of tests necessary to conduct contact tracing and identify hot spots of infection as they crop up, as well as allowing people who have no symptoms to confirm they’re free of disease. All this is essential to get people back to work. Whether that means leaning on big commercial labs or health systems, or getting a new crop of testing gear up and running in hospitals around the country, every effort is a meaningful contribution. “We’re all in this together,” says Khani.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.