Giving up just half your hamburgers can really help the climate

It turns out you can drastically shrink your climate footprint without drastically changing your diet.

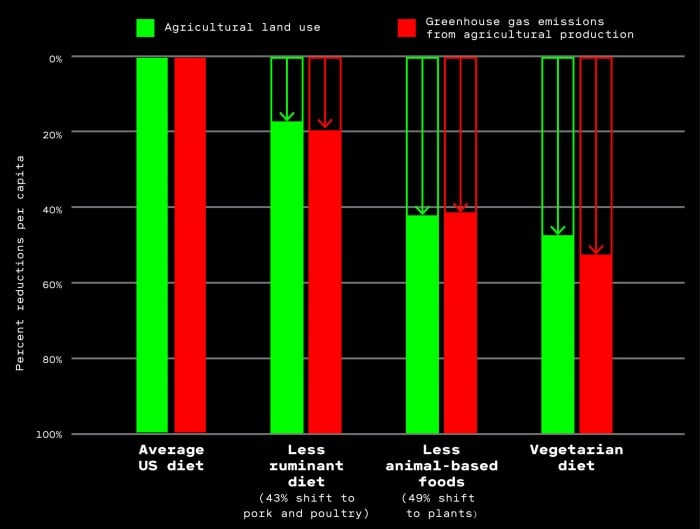

An analysis last month led by the World Resources Institute (WRI) found that there’s not a huge difference, in terms of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, between cutting out about half the red meat—specifically cattle, goats, and sheep—in the average American diet and going full vegetarian.

We see these diminishing returns because a standard vegetarian diet doesn’t replace all meat with vegetables. Instead, it relies heavily on dairy, eggs, and other animal-based products that require a lot of land and produce a lot of emissions, says Tim Searchinger, a senior fellow at WRI and lead author of the report. (Going vegan would produce much deeper cuts, but the report didn’t include that analysis.)

Declines in emissions and land use from reducing consumption of ruminant meat

That’s good news if you want to switch up your diet for climate reasons but find it hard to cut out steaks and burgers altogether. In fact, you can significantly shrink your dietary footprint—which makes up about 15% of US household emissions—without eating less meat at all. Just replacing 43% of your red meat with pork and chicken would cut your dietary emissions by about 18%.

The UN provided a stark reminder today of why thinking through these choices matters a lot. A special report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Climate Change and Land,” concludes that the world needs to overhaul the way it produces food and manages land to rein in global warming and feed a growing population on an increasingly volatile planet.

It notes that agriculture, forestry, and other land use changes account for 23% of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions. Dietary changes can quickly add up. A worldwide shift away from “emissions-intensive foods like beef” could cut anywhere from 0.7 billion to 8 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases per year. At the top end of the range—which would basically be if everyone went vegan—that’s nearly a fifth of all fossil-fuel-related emissions. Such a dietary shift could also free up millions of square kilometers, the report says.

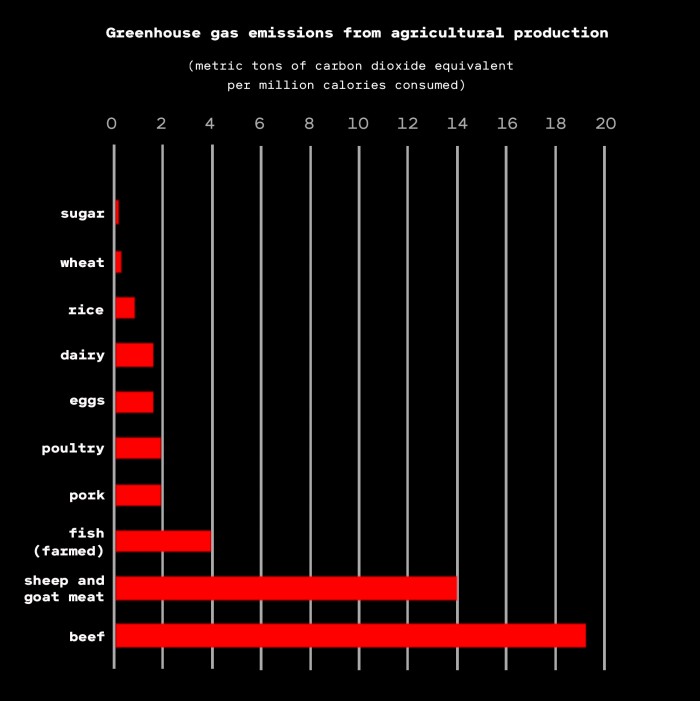

But merely cutting out most red meat can make a big difference, because it comes from ruminants—including cattle, sheep, and goats—that produce an outsize share of particularly powerful greenhouse gases.

The WRI paper stresses that ruminants are “by far the most resource-intensive food,” generating 20 times more greenhouse-gas emissions per gram of protein than pulses—which include chickpeas, lentils, and beans—and four to six times more than dairy. In the average US diet as of 2010, beef contributed 3% of calories, but accounted for 43% of the land use and nearly half the emissions from food production. That, to put it scientifically, is bonkers.

The varying emissions associated with different foods

One reason is the large amount of land needed to produce these animals’ food, whether they graze or eat specially grown crops. Chopping, burning, clearing, or draining forests, peat bogs, and other lands for this purpose releases vast amounts of carbon trapped in the trees, plants, and soil.

But the other big factor is that mammals with multi-chambered stomachs emit huge levels of methane in their burps and manure. That’s one of the most potent greenhouse gases, trapping around 84 times more heat than carbon dioxide during its first two decades in the atmosphere.

But while cutting out red meat is an obvious solution, it’s a tough one. Eating meat is tightly tied up in cultural traditions, social expectations, and perceptions of worth and wealth. As nations become richer, their meat consumption rises. Plus, it tastes really good!

So how can we begin to move the numbers?

WRI’s authors provide some suggestions, including drawing on lessons from marketing, celebrity endorsements, packaging, and product display to change the cultural norms around meat. The government can also employ some powerful sticks and carrots, including taxes, subsidies, and the power to make buying decisions for schools, federal offices, and the military, the report states.

But Searchinger says it will also help a lot for companies to improve the taste, texture, cost, and branding of meat alternatives, such as plant-based substitutes from Impossible Burgers or Beyond Meats.

Changing behavior is hard, but it’s not unprecedented. Americans have already reduced their per capita beef intake in recent decades because of health concerns, changing norms, and the rise of alternatives. “A big reason is chicken became very cheap and very available,” says Dan Blaustein-Rejto, a food and agriculture researcher at the Breakthrough Institute.

He thinks we’re starting to see similar trends with plant-based meats. The Impossible Burger will become available in every Burger King in America starting today, and the US Food and Drug Administration just approved a crucial ingredient that will enable the product to hit retail shelves soon.

Again, not all animal meat has to disappear. Blaustein-Rejto found that if you swapped half the beef sold in American restaurants and fast-food chains for plant-based alternatives, it would cut US agricultural emissions by as much as 58 million metric tons—the equivalent of removing 12 million cars from the roads.

There are other promising technological developments as well. The Dutch conglomerate DSM has developed a methane inhibitor known as 3-nitrooxypropanol, or 3NOP, that was found to cut emissions by 30% in lactating Holsteins. Other researchers are looking at the possibility of feeding cattle a small amount of a type of seaweed that’s been shown to cut methane production by nearly 60%. (See “Seaweed could make cows burp less methane and cut their carbon hoofprint.”)

The IPPC report notes there are more general ways to reduce emissions from livestock, such as managing grazing lands and manure more effectively, switching to higher-quality feed, and selecting or developing animal breeds that, for instance, either fatten up faster or burp out less methane.

Searchinger says we might not have the all tools to zero out meat-related emissions, but we do know how to make a “huge amount of progress.”

“It’s just an issue of taking these things seriously,” he says.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.