Paradise, California, and the impossible choice between climate fight and flight

On the morning of November 8, 2018, clouds of black smoke rose above the community of Paradise, California, raining burning embers on the ridge that some residents initially mistook as hail.

When Gloria Rodgers and Jim Umenhofer spotted the darkening sky from their home on the western edge of town, they knew it was time to pack their cars with all the belongings they could gather. But when they heard the propane tanks around town begin to explode, they knew it was time to leave the rest and go.

By then, thousands of people were piling onto the few streets to safety. It took the couple nearly four hours to reach the edge of town, where the Paradise welcome sign had collapsed in a burning heap in the median strip.

In the end, the Camp Fire destroyed 90% of the town’s homes and killed 85 people.

But eight months after fleeing the deadliest inferno in California’s history, much of that time spent living in a recreational vehicle on a friend’s driveway one town away, Rodgers and Umenhofer are ready to return to Paradise.

They realize that their land, shaded by a canopy of ponderosa pines even after the blaze, has become more dangerous during the four decades they’ve lived there. Climate change has made California’s summers hotter and drier, converting much of the forests and grasslands of the Sierra Nevada foothills into tinder for extended stretches of the year.

“This is the first fire of its kind,” Rodgers says. “I don’t think it’ll be the last fire of its kind, because of what’s going on with the climate.”

But they believe they can rebuild in a safer way. They’ve hired a contractor to draw up plans for a new house that will exceed state and town standards, employing fire-resistant cement building materials in place of their wood shingles and installing vents that slam shut under high heat.

“So yeah, we’re going to rebuild,” Umenhofer says. “But we’re going to harden it up, you bet.”

Rebuild or flee?

Mayor Jody Jones says town officials never entertained the idea that they wouldn’t rebuild in the wake of the Camp Fire (see “The day I tasted climate change”). Instead they’re forging ahead with a plan to resurrect Paradise in a way that they hope will prevent a repeat disaster.

But as climate disasters exact ever higher human, economic, and environmental tolls, society will have to become more pragmatic about whether to rebuild or retreat. Some places will simply become too dangerous to continue living in, and too expensive and hazardous to keep rescuing and rebuilding—if they haven’t already.

The Camp Fire was the world’s most expensive natural disaster for insurers last year, with an estimated $16.5 billion in total losses, according to German reinsurance company Munich Re. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) spent nearly $94 million fighting the blaze. The state and the Federal Emergency Management Agency will pick up the majority of clean-up costs, which could top $3 billion.

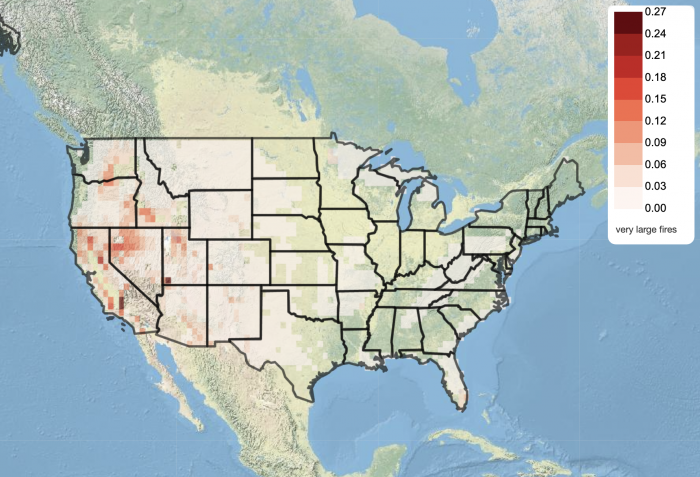

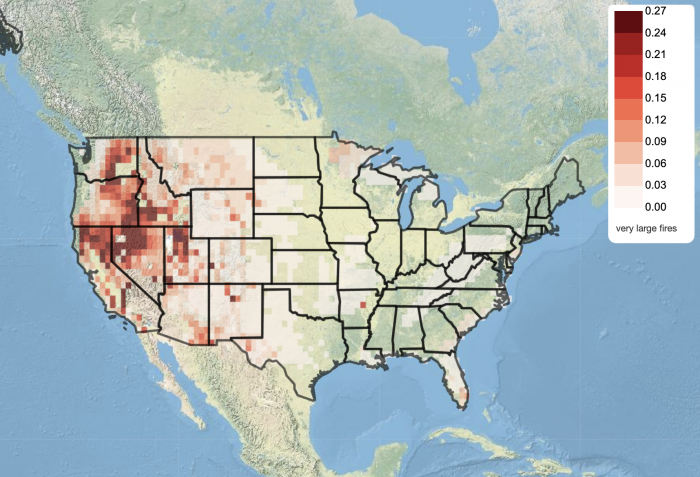

And fire risks will continue to rise. Climate change has already doubled the area burned by wildfire across the western US in recent decades. Under the higher estimates of carbon emissions, the land scorched in Northern California’s forests could double again by 2085, while the risk of “very large fires” will more than triple across vast parts of the American West.

Sea-level rise is likely to be even more disruptive, displacing more than 13 million people in the US and nearly 200 million worldwide by the end of the century, under some of the grimmer climate-change scenarios.

A rising number of researchers are starting to explore the thorny questions these looming dangers present. When should communities stay or go? Who gets to decide? And how do you ask—or force—an entire community to pick up and leave?

“There’s this growing recognition of the inevitability around retreat—and a recognition that actually implementing it is invariably, unbelievably hard,” says Katharine Mach, a senior research scientist at Stanford.

Who pays for Paradise?

So how do we determine whether a city, town, or neighborhood should stay or go after a disaster, or in anticipation of one?

Researchers studying what’s known as “managed retreat” say the decision will turn on four factors. The first three: whether we have the technological means to address the rising risks, whether we can afford them, and whether the cost of the job would exceed the value of the buildings, roads, and other assets that would otherwise be lost.

But the fourth factor will often be the hardest to resolve: social conflicts and public outcries over any decisions to adapt or retreat. People will fight against higher seawalls that lower their property values or block their views. But they’ll also resist abandoning their homes.

Tensions have already emerged in Paradise.

Early last month, the town council moved its monthly meeting from the town hall to the Paradise Alliance Church because of the expected size of the crowd. On the docket that Tuesday evening were 20 fire safety standards that would exceed state rules.

They’re part of a recovery plan that includes bolstering emergency notification systems, widening evacuation routes, and burying the electricity lines that sparked the fire on that November morning. (See “How a town destroyed by fire is trying to make itself fireproof.”)

After a fire that destroyed 19,000 structures, you might expect that everyone would want the strictest fire standards imaginable. But you’d be wrong.

In the lobby before the meeting began, Woody Culleton, stage manager at the Paradise Performing Arts Center and a former town mayor himself, had buttonholed councilman Steve Crowder.

“Now’s the wrong time to pass new laws, to add new mandates,” he said, stressing that it will raise costs for people already struggling to move back.

As another council member, Michael Zuccolillo, walked in, Culleton shouted out, “Vote no on everything.”

State regulations like the wildland-urban interface rules that went into effect in 2008, well after most of the town was built, are adequate to ensure greater fire safety in the future, Culleton told me. Among other things, those standards require fire-resistant roofing materials, and vents that prevent embers from entering the home. Other state building regulations stipulate that plants, trees, and wood piles must be far enough away from structures, and properly spaced and maintained.

But Urban Design Associates, a disaster recovery firm that’s worked with the town since February, proposed further measures, like mandating a five-foot fire break around any structure (which would rule out wood fences running up to a home); eliminating most gutters, except for those above entrances; and requiring sprinklers for all types of homes.

Culleton, who had already begun rebuilding, said those should only be recommended best practices, not rules, unless the town wants to pay for them.

Why, given the disaster he faced, didn’t he just want to move on?

“I’m 74. My mortgage is $550 a month. Where else can I go?” he said.

During the public comment period before the votes, other Paradise residents expressed concerns that the new fire safety standards would cost too much, or sacrifice some of the town’s charm by forcing people to chop down trees.

“You’re taking away some of the risk, but you’re also taking away a lot of the beauty of this town,” Vincent Childs said. “We like the look of the town. It’s forested, it’s shaded, it’s green, it’s beautiful. We are willing to accept some risks.”

In the end, the town council rejected 11, weakened five, and approved four of the proposed standards.

Burnt out

But after several devastating seasons in a row, signs are emerging that California is suffering from fire fatigue. While few are vocally calling for abandoning towns en masse, Ken Pimlott, the recently retired director of Cal Fire, told the Associated Press after last year’s fires that officials need to consider banning new development in high-risk areas. (See “California needs to reinvent its fire policies, or the death and destruction will go on.”)

Home insurers are already becoming stricter about offering policies in fire-prone locations. Over time, that could bring down property values and prevent people from moving to certain areas.

Meanwhile, a recent poll by the University of California, Berkeley, found that three out of four Californians are in favor of limits on new housing in such areas. But the release added that up to one in four Californians, or about 10 million people, already live in places that could qualify as high fire-risk areas, raising questions about where new development and growth could occur.

Some Paradise residents have had enough. Signs litter the yards, fences and billboards along Skyway, the main thoroughfare through town. While many advertise debris clean-up and demolition services, “For Sale” signs seem to outnumber them.

John Gilmore moved down the road to Magalia, California, with his wife, daughters, and dog, and doesn’t plan to return. Standing on the lot where their home used to be, he said the town should be doing even more to reduce fire dangers.

“I don’t know what they think’s going to happen when the next fire comes through with all this dead wood; it’s going to be three times as hot,” he says. “It’s going to be more expensive, but building houses five times in a row if it keeps burning down is expensive too.”

How to beat a retreat

Not every town stays as stubbornly put as Paradise. In fact, governments move communities more often than you might expect. A 2017 Nature Climate Change study by researchers at Stanford University identified 27 cases where the process of managed retreat had at least begun in the last few decades; this could ultimately relocate around 1.3 million people.

The researchers found that relocation is most likely and happens fastest when residents themselves believe they face serious dangers. It also helps when moving them will benefit other people too. For example, the Netherlands relocated a few small communities along the banks of the Rhine to create room for spillways when the river swells. These dramatically lowered the flooding risks for much larger cities upstream.

On the flip side, isolated areas may not get help as readily from the government. For instance, Alaskan villages like Newtok, Shishmaref, and Kivalina have been asking the US government for relocation assistance for years. The settlements have been struggling with coastal erosion, thawing permafrost, fierce storms, and flooding as temperatures and sea levels rise around the Arctic Circle.

But the cost of setting up new, nearby communities with all the necessary infrastructure is high—hundreds of thousands of dollars per resident—while the perceived societal benefit is low. Few Americans have ever heard of the small, remote villages. In 2016, Congress rejected the Obama administration’s proposal to set aside hundreds of millions of dollars for them.

Love of the land

Sitting at a red picnic table set up on what was the front yard of their guest house in Paradise, Rodgers admits she sometimes thinks about buying a quiet farm, with goats and a garden, a good distance from the woods.

It’s tempting to get far away from the next fire in the foothills. And who needs the hassle of rebuilding a home on a lot that won’t get water or electricity for months, and living in a town that will take years to rebuild and repopulate?

But for all the good reasons to move away, she and Umenhofer didn’t consider it for long. When they first returned to their property in January and spotted a family of deer with fawns on the lawn, the same ones they’d noticed on the day they fled, “that sealed the deal,” Rodgers says.

They’ve been making the drive to the property a few times a week to clear burned brush, or simply to spend time on the land. Rodgers has begun gardening a little, planting milkweed, wildflowers, coreopsis, and sweet peas.

As soon as state agencies sign off on soil tests, the town issues permits, and the electricity and water come back, they plan to begin construction. Umenhofer expects to break ground by October.

The land overlooks Little Butte Creek Canyon, a plunging clay and yellow chasm covered by grasses, chaparral, and trees. They’ve watched bucks square off and lock antlers in their backyard. Occasionally a black bear will wander through.

“We were really fortunate to have lived here for 43 years in the forest,” Rodgers says. “It’s not going to be the same. We’ll have a few big pine trees, but we’re not going to be living in the woods anymore.”

“But we feel really attached to the land,” she says, “so I think that’s it for us.”

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Harvard has halted its long-planned atmospheric geoengineering experiment

The decision follows years of controversy and the departure of one of the program’s key researchers.

Why hydrogen is losing the race to power cleaner cars

Batteries are dominating zero-emissions vehicles, and the fuel has better uses elsewhere.

Decarbonizing production of energy is a quick win

Clean technologies, including carbon management platforms, enable the global energy industry to play a crucial role in the transition to net zero.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.