Ovarian cancer is usually diagnosed only after it has reached an advanced stage, with many tumors throughout the abdomen. Most patients undergo surgery to remove as many of these tumors as possible, but because they are so widespread and some so small, it is difficult to eradicate all of them.

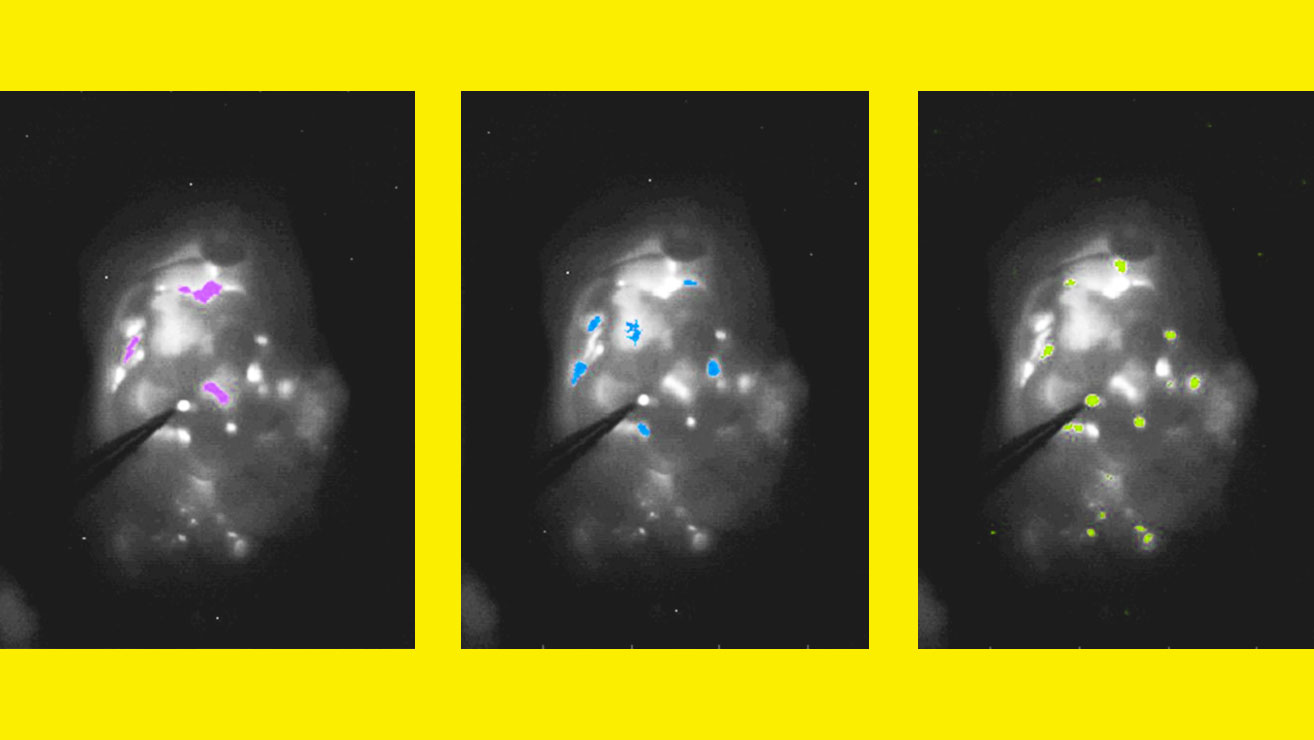

Researchers at MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have now developed a way to improve the accuracy of this surgery. Using a novel fluorescence imaging system, they were able to find and remove tumors as small as 0.3 millimeters—smaller than a poppy seed—during surgery in mice. Mice that underwent this type of image-guided surgery survived 40% longer than those that had tumors removed without the guided system.

“What’s nice about this system is that it allows for real-time information about the size, depth, and distribution of tumors,” says biological engineering and materials science professor Angela Belcher, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and head of the Department of Biological Engineering.

With help from researchers at MIT Lincoln Lab, the team adapted near-infrared imaging to help surgeons locate tumors during surgery by providing continuous, real-time imaging of the abdomen, with tumors highlighted by fluorescence.

The researchers are seeking FDA approval for a phase 1 clinical trial to test the imaging system in humans. In the future, they hope to adapt it for early diagnosis of ovarian cancer, which is easier to treat if caught earlier.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.