Why AI researchers should reconsider protesting involvement in military projects

Technology industry workers who protested against contracts with the military should reconsider their position, according to one Department of Defense advisor.

Brendan McCord—an AI expert who was involved in Project Maven, the DoD’s program to accelerate artificial intelligence and machine learning for military uses—said that “constructive engagement” with the armed forces was necessary to avoid bad decisions.

In June, Google said it would no longer work with Project Maven after more than 4,000 employees signed a letter that accused the company of being “in the business of war.”

But speaking at EmTech Digital, MIT Technology Review’s AI conference, McCord said that it would be better for society as a whole to see such collaborations continue, and for those dissenting employees involved in AI projects to reexamine their stance.

“Most here today would agree that militaries and their role in deterrence, offense, and defense are a part of the world, and they will be for the foreseeable future,” he said. “A strategy of constructive engagement versus one of opting out is a far more optimal one.”

“Working on AI for defense does not make you less principled,” he added.

The secretive nature of Project Maven, which was said to be focused on improving analysis of footage captured by military drones, had caused concern across a wide group of AI researchers. But the US armed forces remain a “powerful force for promoting peace and stability in the world,” said McCord, reflecting arguments that AI researchers who reject the military on principle are actually handing the advantage to those with less rigorous ethical standards, including other nations.

While McCord said he would not expect “antiwar pacifists” to change their minds, he asked researchers to consider what would happen if other countries were making their own advances in emerging fields. A more positive attitude to the military was particularly important, he added, since governments now play a lesser role in the development of new technological discoveries than they once did.

“At the end of the Cold War the locus of innovation shifted to the private sector,” he said. “The world has changed. The capacity for government, and the role of government, has been diminished to a point where it’s never been so low in my view. The net effect is that big tech companies have assumed the mantle—whether they wanted to or not—of being the arbiters. They’re often self-regulating.”

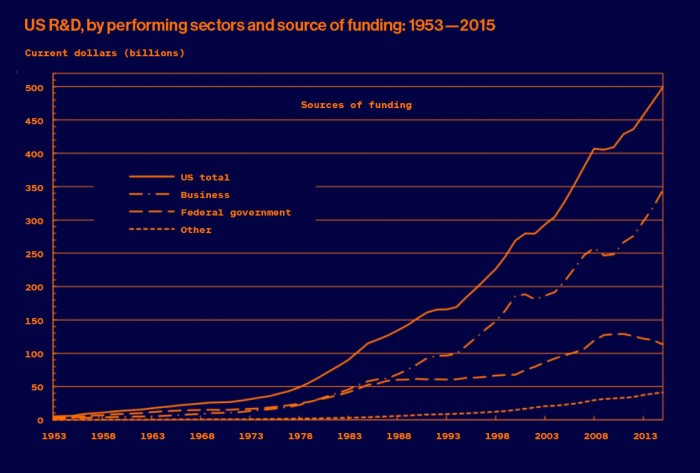

Many major technological developments, including the internet, GPS, and virtual assistants, have come as a result of investment from the Department of Defense. But since the end of the Cold War, the DoD’s research and development spending has dwindled. In the mid-1980s, government and private R&D budgets were roughly equal—around $55 billion annually. Since then the government has doubled its investment, while private companies, including the likes of Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon, have dramatically increased private budgets to more than $350 billion each year.

However, while big tech companies may not be transparent about their work, the government has come in for criticism of its own. It was reported earlier this week by the Intercept that the Pentagon has rejected Freedom of Information requests for data on Project Maven, claiming its documents are exempt from public scrutiny.

McCord retains an advisory role at the Department of Defense, but he recently left his full-time job there to join the private sector. He now has a senior position at Tulco Labs, a new company focused on innovation at work founded by the entertainment billionaire Thomas Tull.

He finished by saying that it’s imperative for industry employees to help keep their employers in check, quoting the biologist and theorist E.O. Wilson.

“The real problem of humanity,” he said, “is that we have paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technology.”

Deep Dive

Artificial intelligence

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

What’s next for generative video

OpenAI's Sora has raised the bar for AI moviemaking. Here are four things to bear in mind as we wrap our heads around what's coming.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.