Crowdsourced maps should help driverless cars navigate our cities more safely

Our current street maps aren’t much good for helping driverless cars get around. Although we’ve mapped most roads, they get updated only every couple of years. And these maps don’t log any roadside infrastructure such as road signs, driveways, and lane markings. Without this extra layer of information, it will be much harder to get autonomous cars to navigate our cities safely. Robotic deliveries, too, will eventually require precise details of road surfaces, sidewalks, and obstacles.

A Swedish startup called Mapillary thinks it has the answer. It’s an open platform that crowdsources images of streets taken by people on their smartphones: a sort of Wikipedia of mapping. It says it is now one of the biggest publicly available databases of street-level imagery in the world.

“Driverless cars need the latest view of the road,” says CEO Jan Erik Solem. “They require a higher and higher update frequency for maps, from quarterly to monthly to weekly to daily. The only scalable way to do that is using technology.”

There are a number of approaches to gathering mapping data, and there’s competition among startups within the field. Mapillary says it is different because it is crowdsourced—unlike, say, Google’s proprietary Street View, which is updated every couple of years. Because anyone can contribute to its platform, it gets updated every day.

This approach is similar to OpenStreetMap, which launched in 2004 and provides a free, editable map of the world, but it doesn’t log any of these additional roadside details.

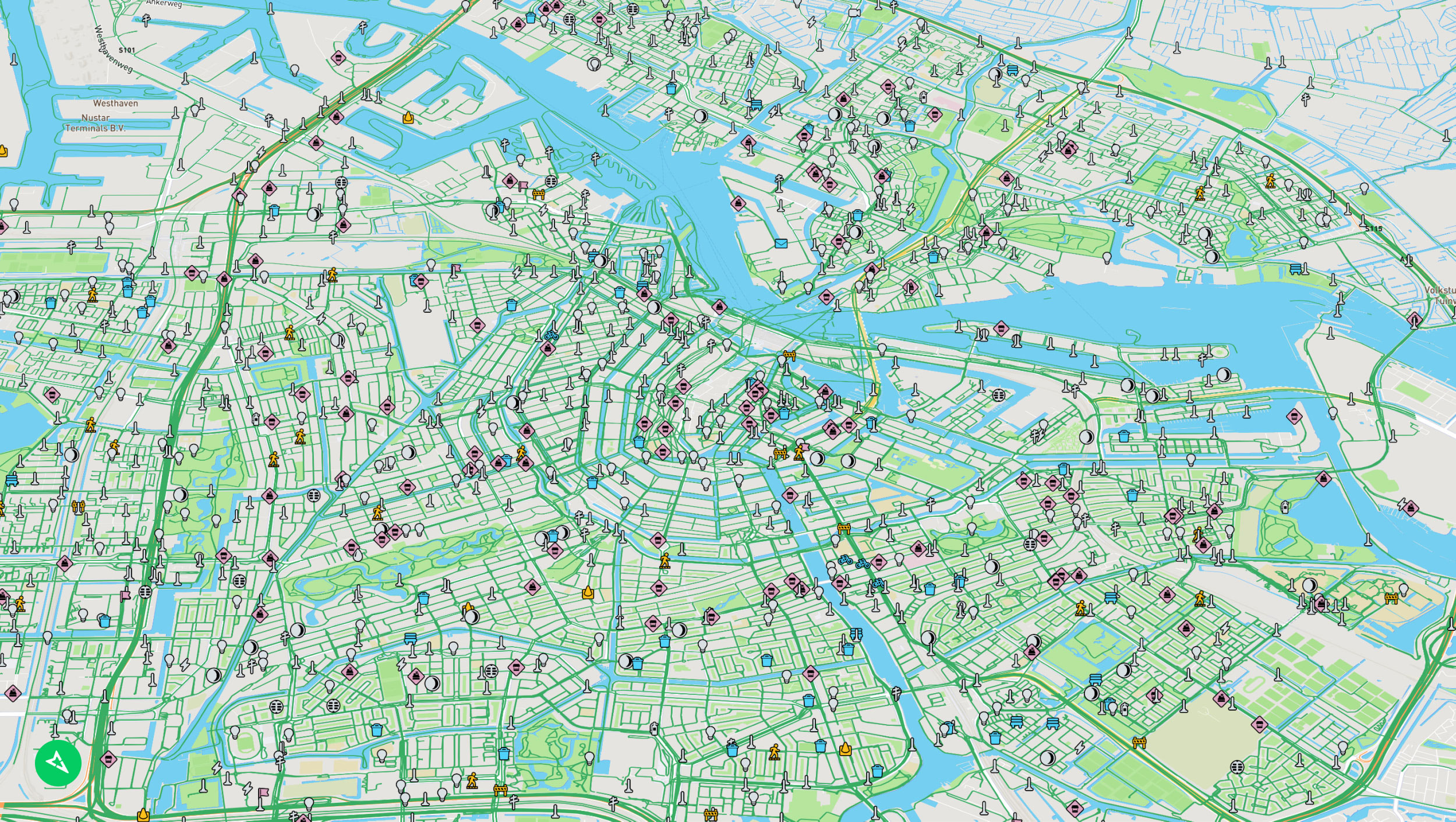

Mapillary uses computer-vision software to analyze the crowdsourced images and identify objects. Its database of 422 million images covers 6.2 million kilometers (3.9 million miles) of the globe. And it’s growing all the time: its software has just put 186 million objects, like utility poles, benches, and manhole covers, on the map, locked to a specific location with coordinates.

Once the images are uploaded, the software analyzes them for objects and identifies them. The maps are then made available for anyone to see online. The service is free for charities and for educational or personal use, but commercial customers have to pay a license fee.

Mapillary is already being put to use. The city of Amsterdam, transport officials in Vermont and Arizona, and even the country of Lithuania are using the firm’s maps to improve their understanding of their streets.

“If you look at any object on a street, someone is responsible for it. It all has to be catalogued and checked,” says Steven Hewett, who works for the city of Clovis in New Mexico.

Clovis is using Mapillary to make sure it’s fulfilling its obligations to residents by keeping driveways clear, signs up to date, and roads clear of potholes. The city used to do this by paying a contractor to go around and painstakingly log every mailbox, fire hydrant, and stop sign, for a few dollars each.

It has now automated virtually the entire process using Mapillary. “Without this software, we’d be walking around collecting all the data by hand, and I can’t even guess how long that’d take for a 23-square-mile city,” Hewett says.

Gabriel Brostow, a computer science professor at University College London, agrees that this kind of mapping needs to be automated to be scalable. “Millions of square kilometers in the world can’t be updated by humans as quickly as they could be by algorithms,” he says.

One day, driverless cars could be both consumers and producers of this data, capturing street-level imagery as they travel (both faces and license plates are automatically blurred out by Mapillary’s software). Indeed, Hewett foresees a future where networked vehicles can automatically identify issues like fallen trees in the road, or traffic accidents, and automatically notify the relevant public authorities.

The data could also help equip cities with better knowledge of their streets so they can improve public transport and accessibility for disabled people, Brostow adds.

*This story was corrected to make clear the images are crowdsourced but the underlying code is not open source.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.