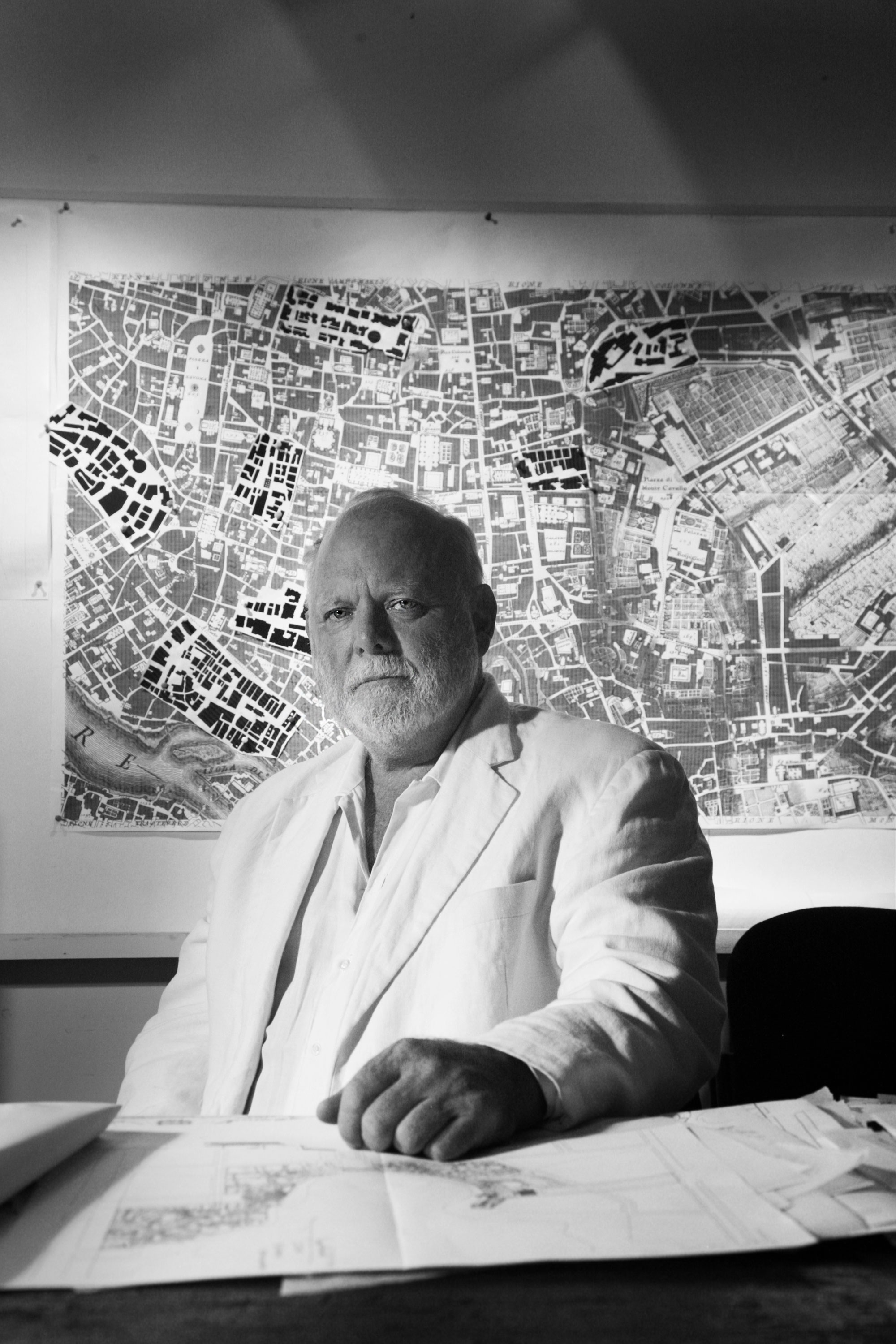

Perhaps Benjamin Wood, MArch ’84, should have known he was destined to become an architect when, at age eight, he constructed an elaborate multiroom treehouse. Instead, he became a civil engineer, flew fighter jets for the US Air Force, and opened a restaurant. But he found himself drawn to architecture again and again, and he finally made it his profession after earning a master’s degree from MIT in his 30s. Now, decades later, Wood is using his skills to change the urban landscape in China.

Wood made a name for himself with projects such as Spitalfields Market in London, the renovation of Soldier Field (the Chicago Bears’ stadium), and Lincoln Road and the Art Deco District in Miami Beach. But in 2004 he moved to Shanghai, where he currently heads Studio Shanghai. For Wood, China represents the ultimate architectural opportunity: “There’s never been an economy that has grown so fast and gotten so big in such a short time in [modern] history,” he says, adding that during his two decades in the country, millions have moved from small, rural villages into cities.

One of Wood’s most famous projects is Xintiandi, or “New Heaven and Earth,” which he says is “probably the most successful cultural entertainment destination in the world.” The Shanghai development offers car-free shopping, eating, and entertainment, and it is visited by millions every year. When designing it, Wood made an unusual decision: he incorporated the historical brick townhouse buildings near the old French Concession district rather than demolishing them. The project was wildly successful and his approach copied so often that “to Xintiandi” has become a verb.

“Because of my work on Xintiandi, the whole attitude toward historic neighborhoods has changed,” Wood says. “I’m not a historic preservationist, but I demonstrated to the rest of China that you could take some very ordinary buildings and through a very humane approach to architecture, you could create a cultural and entertainment destination.”

As Wood’s reputation in China has grown, so have his opportunities to shape its cities. Currently, half of Wood’s work is through public-private partnerships, where the government redoes entire blocks at a time.

And although he recently turned 71, he has no plans to retire. “A lot of architecture is asking the right questions and optimizing the variables, and that takes decades of experience to really do well,” he says. “If you live long enough, remarkable things come your way—I guess that’s why I’m going to keep working, because who knows what’s over the next horizon.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.