Wireless from water to air

MIT Media Lab researchers have taken a step toward solving a long-standing challenge with wireless communication: direct data transmission between underwater and airborne devices.

Today, underwater sensors cannot share data with those on land, because both use wireless signals that work only in their respective mediums. Radio signals traveling through air die rapidly in water; acoustic signals, or sonar, sent by underwater devices mostly reflect off the surface without breaking through. Buoys have been designed to pick up sonar waves, process the data, and shoot radio signals to airborne receivers. But they can drift away and get lost, and many are needed to cover large areas.

Assistant professor Fadel Adib and his graduate student Francesco Tonolini are tackling this issue with a direct underwater-to-air transmission system, called “translational acoustic-RF communication” (TARF). “Trying to cross the air-water boundary with wireless signals has been an obstacle. Our idea is to transform the obstacle itself into a medium through which to communicate,” Adib says.

In the system, a standard acoustic speaker transmits sonar signals to the water’s surface, which travel as pressure waves of different frequencies corresponding to different data bits. To send a 0, the transmitter can send, say, a wave traveling at 100 hertz; for a 1, it can transmit a 200-Hz wave. When the signal hits the surface, it causes tiny ripples in the water, only a few micrometers high, corresponding to those frequencies.

Positioned in the air above the transmitter is an extremely high-frequency radar that processes signals in the millimeter-wave spectrum of wireless transmission, between 30 and 300 gigahertz. The radar—which looks like a pair of cones—sends a radio signal that reflects off the vibrating surface and rebounds back with a slightly modulated angle corresponding to the sent data. A vibration on the water surface representing a 0 bit, for instance, will cause the reflected signal’s angle to vibrate at 100 Hz. That bit is then decoded.

The researchers tested TARF in swimming pools at MIT, with swimmers disturbing the surrounding water. The transmitter was submerged up to 3.5 meters below the surface, and the receiver was positioned up to 30 centimeters above. TARF accurately decoded messages—such as “Hello! from underwater”—at hundreds of bits per second, similar to standard data rates for underwater communications. A paper describing the system and the results was presented at this year’s Sigcomm conference.

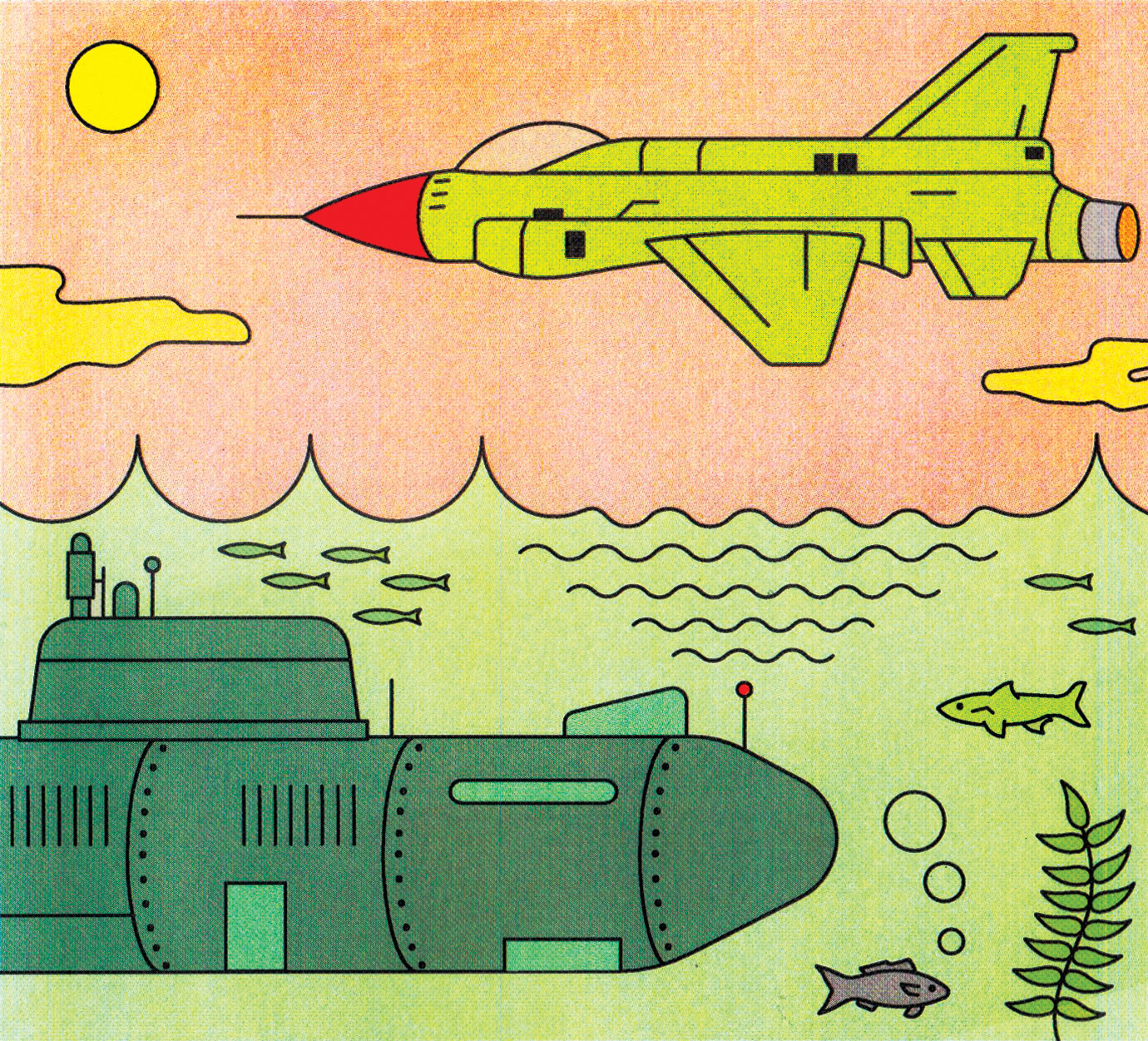

The system could open new capabilities for water-air communication, Adib says. Military submarines could communicate with airplanes without surfacing and compromising their locations. Underwater drones that monitor marine life wouldn’t need to constantly resurface from deep dives to send data to researchers, which is inefficient and costly. The system could also help find planes lost underwater. “Acoustic transmitting beacons could be implemented in, say, a plane’s black box,” Adib says. Then they could send signals periodically for search planes to decode.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.