Investigators searched a million people’s DNA to find Golden State serial killer

Investigators may have compared a serial killer's DNA with that of one million unwitting genealogy enthusiasts as part of an investigation that led to the arrest earlier this week of a man accused of being California’s elusive “Golden State Killer.”

“I had no knowledge this was happening,” says Curtis Rogers, co-creator of GEDMatch, an ancestry site that a police source yesterday identified as one of those employed by investigators.

Officials in California said they had found and arrested Joseph James DeAngelo, 72, for a fearsome series of murders and rapes between 1974 and 1986 after using commercial genealogy websites, including GEDMatch, to locate one of his relatives.

GEDMatch, a no-frills website that has never advertised, is used by amateur and professional genealogists to upload and compare DNA tests, effectively crowdsourcing vast family trees.

It has been growing quickly and is now approaching one million users, says Rogers.

John Wilbanks, chief commons officer at Sage Bionetworks, calls the police activity an “exploit” of the community that raises privacy questions.

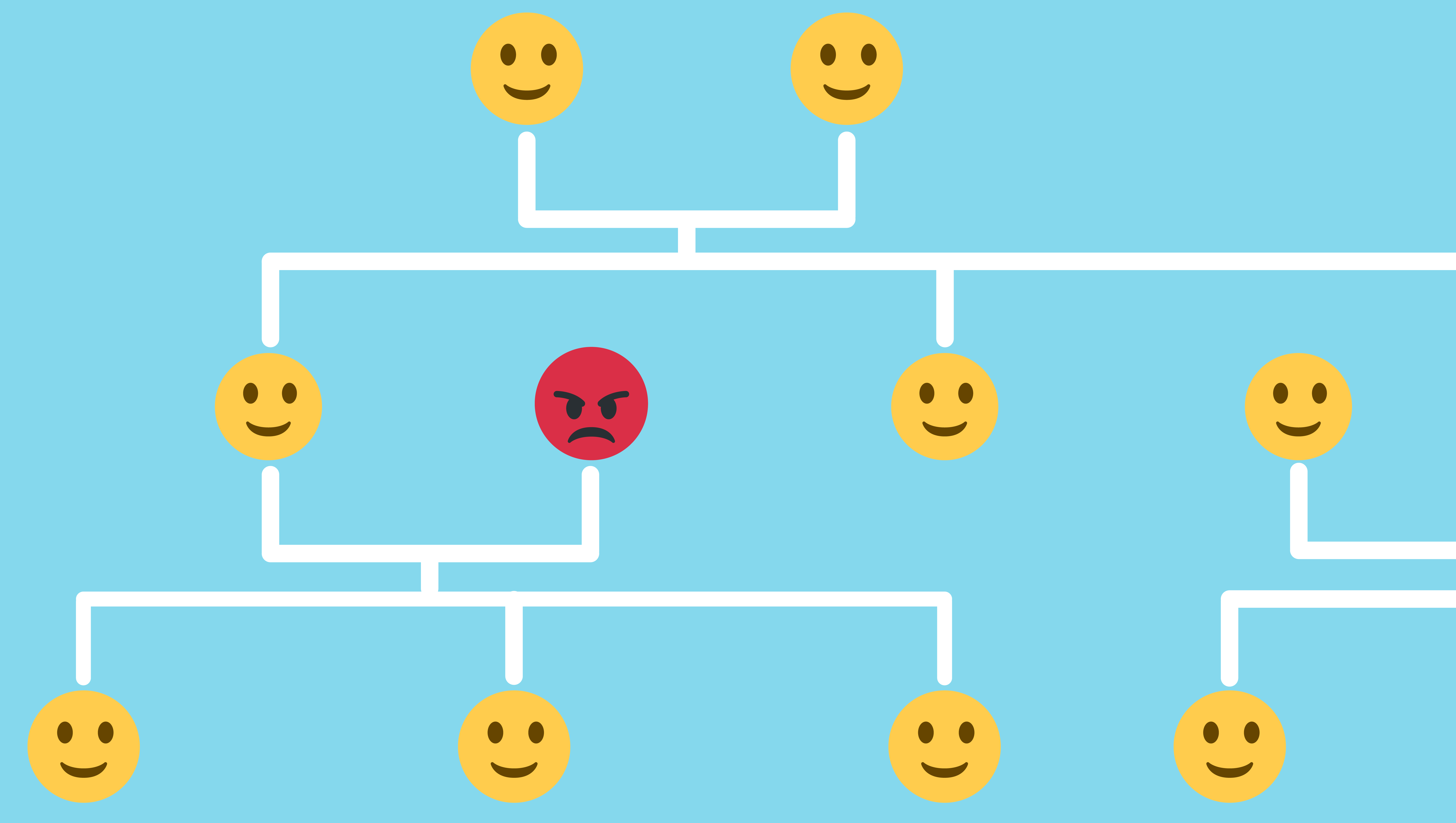

While not all details of the sleuthing are known, it appears likely that investigators uploaded DNA data about the killer obtained from old crime-scene evidence and used it to find one of his relatives.

That’s possible because the genetic code of siblings, cousins, and other relatives is partly identical. Once detectives found a relation, they could have used conventional methods to zero in on DeAngelo.

Users uploading genetic data into the GEDMatch website currently have to click on a button saying that the DNA is theirs “or the DNA of a person for whom you are a legal guardian or have obtained authorization.”

Rogers didn’t say whether he thought police had acted legally or not, but he says the rule on his website is that “it’s only with a person’s permission.”

Investigators, of course, didn't have authorization from DeAngelo to use his DNA. However, it seems likely they would not have needed it. “Under current constitutional law, the government has a tremendous amount of discretion in how to use crime-scene evidence,” says Erin Murphy, a professor of law at New York University. “DNA abandoned by the perpetrator of a crime basically has no legal protection.”

Catching a killer

It was only a matter of time before detectives took advantage of the booming business of genetic genealogy, in which consumers order $99 spit kits to have their DNA analyzed, learn about their heritage, and connect with relatives.

As of early this year, more than 12 million people had undergone such tests, mostly from 23andMe and Ancestry DNA, and the number is growing by about one million each month. That’s reaching the point where nearly everyone in the US will have a close relative, cousin, or second cousin who has given a DNA sample.

Users of GEDMatch are warned that they have no guarantee of privacy and that their data could be used for purposes other than genealogy. (In practice, it takes only a few clicks to upload other people’s DNA files and start looking at their relatives.)

Rogers posted a notice telling people they could take down their profiles if they wished. He said that so far “very few” had done so.

What creates potential privacy concerns is that investigators may have taken advantage of the site’s informality to upload the killer’s data and then effectively search the DNA of all the other users.

Wilbanks says most users would have expected authorities to take some formal steps before that kind of search, even if the site made no such promise, rather than “show up impersonating someone who wants to connect to cousins.”

New technology

California already maintains a large DNA database of around two million convicted felons. That database is also used for family searches. In 2010, for example, the arrest of a young man on weapons charges led to the identification of his father as the “Grim Sleeper,” an LA serial killer.

However, family searches in police and FBI databases are limited. That is because forensics labs use an older DNA technology, called “short tandem repeats.” These genetic markers can be used to accurately identify only very close relatives, such as a parent or a sibling.

Commercial genealogy databases, however, are larger and use broader maps of a person’s genome, making them a far more effective way to find relatives. “It’s much, much, much, better,” says Yaniv Erlich, a professor at Columbia University and chief scientist of MyHeritage.

These maps, created using DNA chips, employ measurements of about half a million “SNPs,” specific locations where one person’s DNA may vary from another person’s.

It appears possible that investigators returned to the Golden State crime-scene samples to generate up-to-date SNP information about their suspect.

In announcing DeAngelo’s arrest, Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones said detectives had used “emerging DNA technology,” a possible reference to such steps.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.