A cheap and easy blood test could catch cancer early

A simple-to-take test that tells if you have a tumor lurking, and even where it is in your body, is a lot closer to reality—and may cost only $500.

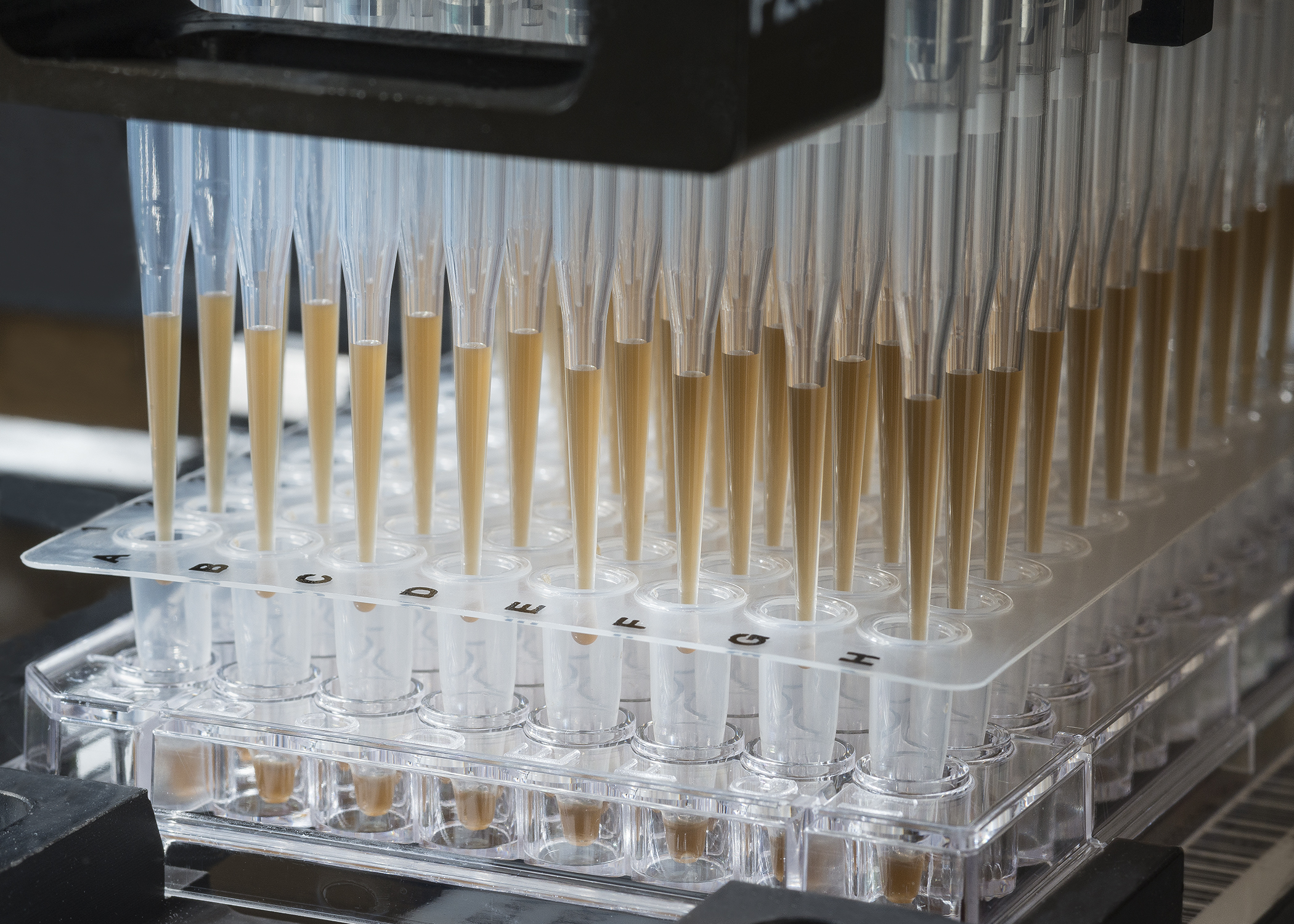

The new test, developed at Johns Hopkins University, looks for signs of eight common types of cancer. It requires only a blood sample and may prove inexpensive enough for doctors to give during a routine physical.

“The idea is this test would make its way into the public and we could set up screening centers,” says Nickolas Papadopoulos, one of the Johns Hopkins researchers behind the test. “That’s why it has to be cheap and noninvasive.”

Although the test isn’t commercially available yet, it will be used to screen 50,000 retirement-age women with no history of cancer as part of a $50 million, five-year study with the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, a spokesperson with the insurer said.

The test, detailed today in the journal Science, could be a major advance for “liquid biopsy” technology, which aims to detect cancer in the blood before a person feels sick or notices a lump.

That’s useful because early-stage cancer that hasn’t spread can often be cured.

Companies have been pouring money into developing liquid biopsies. One startup, Grail Bio, has raised over $1 billion in pursuit of a single blood test for many cancers.

For their test, Hopkins researchers looked at blood from 1,005 people with previously diagnosed ovarian, liver, stomach, pancreatic, esophageal, colorectal, lung, or breast cancer.

Their test searches for a combination of eight cancer proteins as well as 16 cancer-related genetic mutations.

The test was best at finding ovarian cancer, which it detected up to 98 percent of the time. It correctly identified a third of breast cancer cases and about 70 percent of people with pancreatic cancer, which has a particularly grim outlook.

The chance of a false alarm was low: only seven of 812 apparently healthy people turned up positive on the test.

The researchers also trained a machine-learning algorithm to determine the location of a person’s tumor from the blood clues. The algorithm guessed right 83 percent of the time.

“I think we will eventually get to a point where we can detect cancer before it’s otherwise visible,” says Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society.

He cautions that screening tests can sometimes harm rather than help. That can happen if they set off too many false alarms or if doctors end up treating slow-growing cancers that are not likely to do much harm.

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

The quest to legitimize longevity medicine

Longevity clinics offer a mix of services that largely cater to the wealthy. Now there’s a push to establish their work as a credible medical field.

There is a new most expensive drug in the world. Price tag: $4.25 million

But will the latest gene therapy suffer the curse of the costliest drug?

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.