This Gadget Has a Real Working Menstrual Cycle

A virtual representation of a human being is known as an avatar. But what about a biological representation of the female reproductive organs?

That would be “Evatar.”

We’ve seen other organs-on-chips before, acting like little lungs or livers. Now Evatar, say its creators, is the first laboratory gadget able to copy a 28-day menstrual cycle, during which an egg matures and gets released.

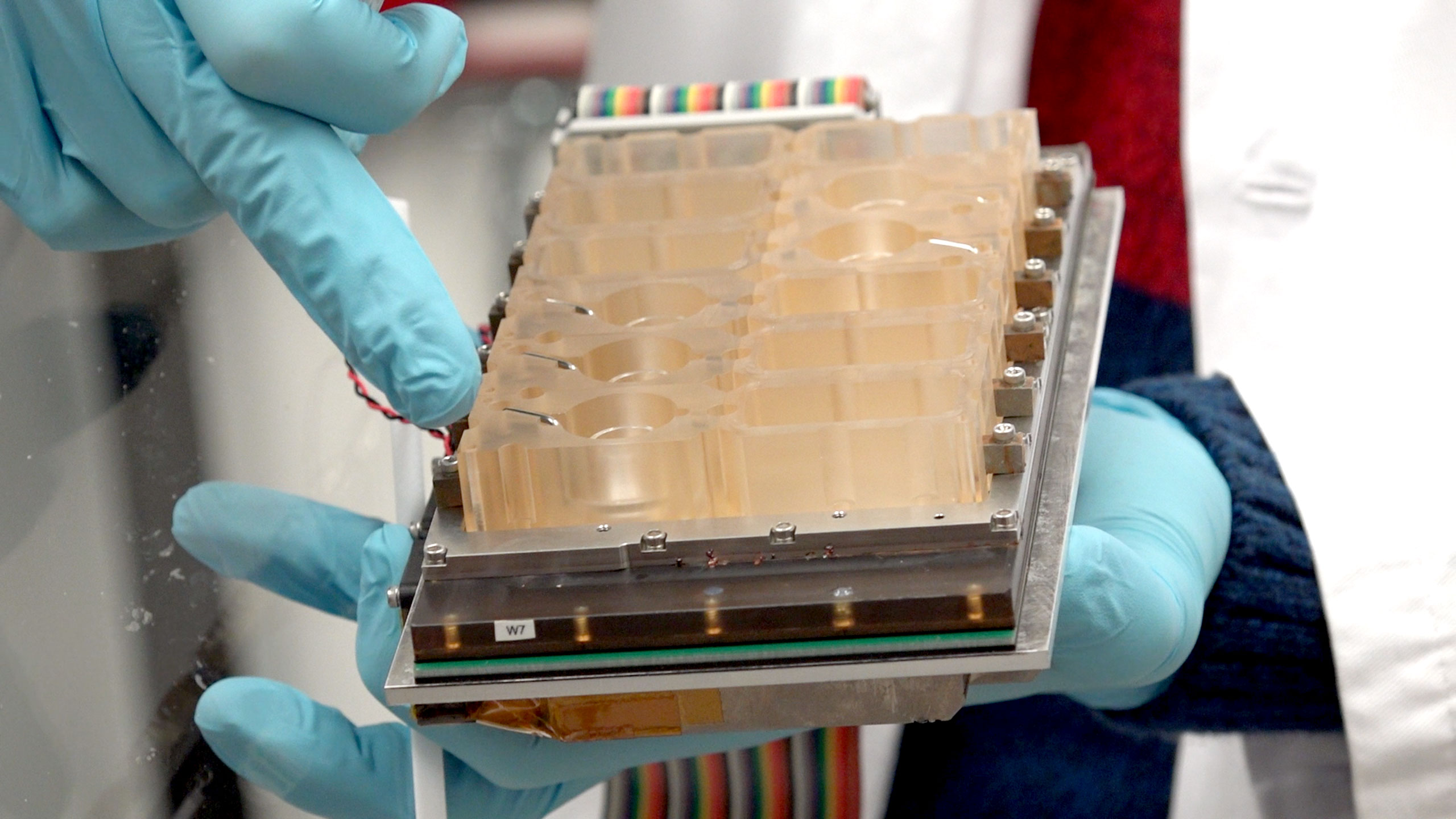

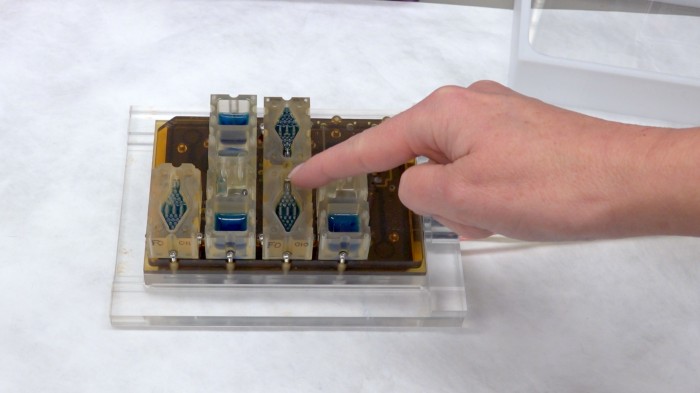

The device is about the size of a paperback book, with plastic compartments designed to mimic a woman’s ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and liver. Evatar has real human cells in it, obtained from women undergoing surgery for other reasons. A mini-liver was included because that’s the organ that metabolizes drugs.

Scientists at Northwestern University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Draper Laboratory, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, say they built Evatar by growing each tissue type in its own plastic compartment, connecting them with a network of tiny tubes. Twenty electric micro-pumps circulate a blue cocktail of nutrients and hormones, which serves as a blood substitute and lets the tissues communicate.

To test whether the chip could ovulate, the researchers added a mouse ovary (human ovaries aren’t easy to obtain). Within 14 days, according to their report in Nature Communications, the ovary released an egg.

Teresa Woodruff, a reproductive scientist at Northwestern University who led the project, says her team is also working on a male version. It may eventually also be possible, she says, to take tissue samples from any woman and, using stem cells, create a “personalized Evatar.”

With Evatar, scientists have come a little closer to creating an entire “body-on-a-chip” that could simulate a person’s physiology. Jonathan Coppeta, a biosystems and tissue engineer at Draper, says the artificial menstrual cycle might let drugmakers safely explore new contraceptives or test treatments for diseases like fibroids, endometriosis, and cervical and ovarian cancers. “Historically, women’s physiology has been underrepresented in the drug development pipeline,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.