Pig-Human Organ Farming Doesn’t Look Promising Yet

In research that has rattled policy makers from Washington to the Vatican, scientists in California today described their controversial first attempts to create pigs with human organs inside them.

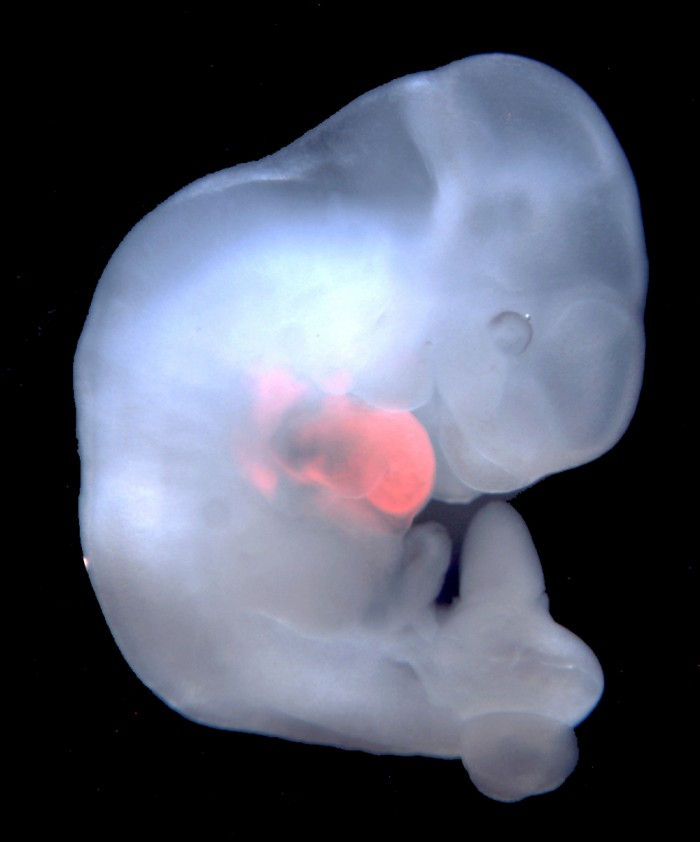

The experiments involved fusing human stem cells into animal embryos and then trying to grow the resulting "chimeras" into fetal animals whose tissue is partly human.

Scientists at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, injected human stem cells into more than 2,000 pig embryos, then allowed these to gestate for up to four weeks in surrogate sows. Their work was described on Thursday in the journal Cell.

The effort was not particularly successful: few human cells survived, and they did not contribute to the developing animals in a meaningful way. Still, the scientists call the work a first step toward “human organ generation” in barnyard animals. Tens of thousands of people die each year awaiting organ transplants.

The existence of such human-animal chimeras was first reported last year in MIT Technology Review, when we described how several scientific teams had established pregnancies of pig and sheep embryos that contained added human cells.

As in the new report, none of the animals were allowed to develop more than a few weeks, and none have been born. The slim contribution of human cells is also likely to cool fears of monstrous results.

Still, the new line of research has been under the scrutiny of policy makers. Citing concerns that the experiments could lead to unexpected outcomes, like a pig with an all-too-human brain, the National Institutes of Health placed a moratorium on funding the work in late 2015.

The agency later proposed lifting the ban, subject to restrictions and oversight by a special committee.

The new policy was open for public input and the NIH said it had received 22,000 comments, mostly opposing it. The majority of comments were generated through a letter-writing campaign organized by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and associated pro-life organizations. The letters complain about the use of tax dollars to fund research involving “beings whose very existence blurs the line between humans and non-human animals.”

Carrie Wolinetz, director of the office of science policy at the NIH, said the agency had no timeline for finalizing the policy, which some observers expect could draw opposition from the new administration of Donald J. Trump. “We have had no conversations with the new administration about this,” she said. “They haven’t brought it up and we are continuing on our path.”

The newly published work was carried out in the lab of Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a Salk Institute scientist who specializes in studying embryos and cells derived from them.

Belmonte told Scientific American in January 2016 that Pope Francis had personally given him permission for the research. But the Vatican later disputed the claim, calling it “absolutely untrue." Salk said Belmonte was unavailable for comment.

The technology involves combining versatile stem cells from one species into the early embryo of another, when it is a ball of just 150 or so cells. The goal is to create an animal with a mixture of cells from both—a chimera.

Scientists have already had success fusing closely related species. On Wednesday, biologist Hiromitsu Nakauchi of Stanford University reported in Nature that he’d grown a mouse pancreas in a rat and then transplanted the tissue back into diabetic mice, succeeding in reversing the disease.

In his report, Belmonte also showed he could mix rodents, including creating mice with patches of rat tissue, including fur.

To give donated cells a better chance of surviving, and to channel their activity, Belmonte and lead project scientist Jun Wu also explain how they modified mouse embryos with the gene-editing technique CRISPR in order to inactivate the specific genes mice require to develop a pancreas, heart, or eye. Animals lacking those genes will normally die or be born deformed.

But if embryonic cells from a rat are added, they will fill in for the missing mouse cells and the organs turn out normal. The same strategy is envisioned as a way to channel human cells to grow into specific organs, such as a kidney, inside animals such as a pig or sheep.

But Belmonte’s results show that it was difficult to get any human cells to survive in pig embryos and contribute to a developing fetus. Their best effort resulted in only a minimal number of human cells. It’s likely that the larger genetic distance between pigs and man is to blame.

Nakauchi called the results “essentially negative” and consistent with experiments he has also carried out on human-animal hybrids. “We find surviving human cells, but they are not integrated and co-developing,” he says.

Pablo Ross, a veterinarian at the University of California, Davis, and a co-author of the new paper, said transfer of human-animal embryos to sows or other animals would continue, but at a slower pace, as the team explores different tricks that might allow the human cells to flourish, including first using CRISPR to edit the pig embryos.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.