Would You Feel Sexy Wearing Eau de Extinction?

The synthetic biology company Ginkgo Bioworks says it is developing a fragrance line that will contain smells from plants that have gone extinct in the last 200 years.

Ginkgo plans to make the scents by grafting DNA from extinct plants into yeast grown in its “DNA brewery,” a large genetic engineering facility it operates in Boston.

Scientists interested in “de-extinction” are still pretty far from being able to use genetic engineering to resurrect animals like the woolly mammoth or passenger pigeon. But they are a lot closer when it comes to conjuring lost scent molecules.

“We will not bring back the plant, but we hope that by experiencing the scent of the flower that went extinct, people will get a greater appreciation for plants that are lost,” says Christina Agapakis, creative director at Ginkgo.

The effort, like all perfume making, is as much an artistic project as a scientific one. But manufacturing of commercial fragrances and flavors in vats of yeast has already become commonplace. Tom Ford’s Patchouli Absolu, for example, uses patchouli fragrance produced in yeast cells genetically modified by Amyris, a competing synthetic biology company in Emeryville, California.

Ginkgo, which raised $100 million from investors this year, also engineers yeast to mimic a plant’s biochemical pathways and generate fragrance compounds called terpenes, which are hydrocarbon molecules found in aromatic plant oils. Terpenes typically have a strong odor like the sharp citrusy smell of orange peel, the floral notes of lilac, or the menthol notes in mint.

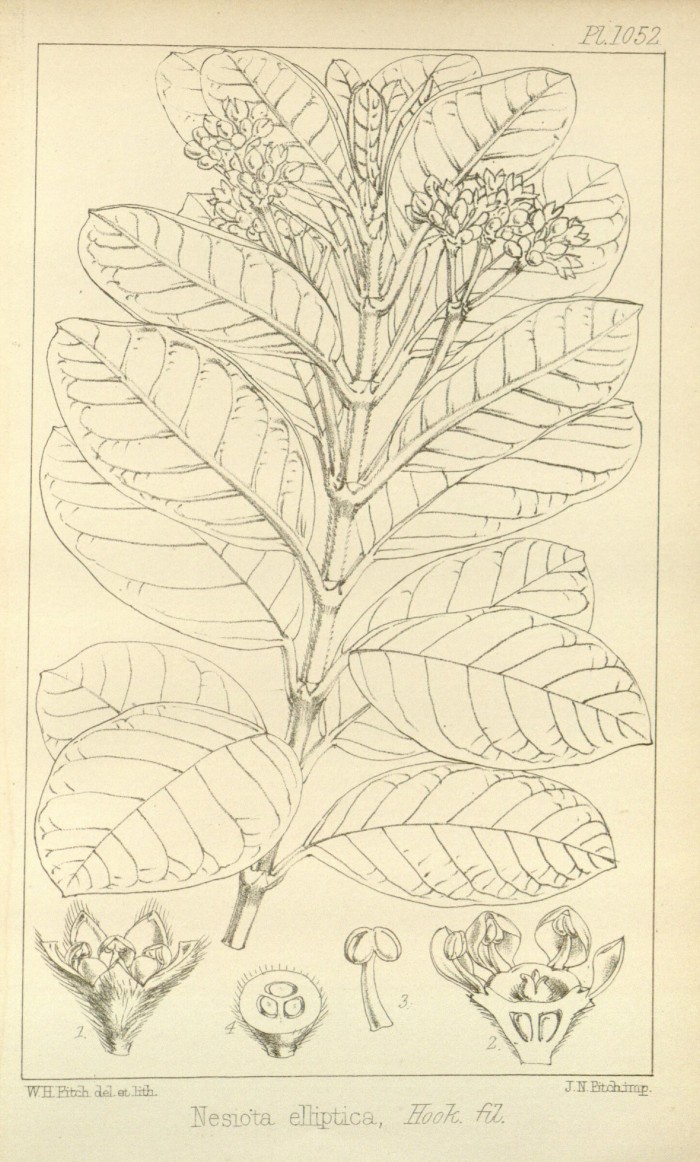

To locate new terpene-making genes, in May of this year Agapakis and colleagues scoured the archives of the Harvard University Herbarium, which houses more than five million preserved plant specimens. They selected samples of a dozen species that have gone extinct in the last two centuries, including a Hawaiian hibiscus and Nesiota elliptica, a flowering olive bush native to the island of St. Helena’s in the South Atlantic, which disappeared from the wild in 1994 and went extinct in 2003.

The next task—as yet incomplete—is to extract the extinct DNA molecules. For that, the samples were sent to Beth Shapiro, author of How to Clone a Mammoth and an expert on ancient DNA, whose paleogenomics lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz, excavates animal bones in the Artic permafrost and has perfected methods for sequencing old DNA.

Jay Keasling, a metabolic engineer and cofounder of Amyris, says the project could “find some novel molecules that you wouldn’t have access to naturally,” but he adds that it won’t really be possible to tell what the plant smelled like, because that scent “has to do with all the other molecules inside the plant,” not only the terpenes.

Isaac Sinclair, a perfumer with Symrise, a German fragrance and flavor manufacturer and a collaborator of Ginkgo’s, agrees that the final scents will be open to interpretation. He says that’s just part of the art of making commercial perfumes.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.