Despite Fears, This Election Could Be More Secure Than Ever

Fear that hackers could exploit vulnerabilities in our voting systems could undermine voter confidence this November, especially if the vote ends up being close. The good news is that it is also helping fuel an important discussion about how the U.S. should secure its elections.

Recent hacks on the Democratic National Committee, for which the White House has officially blamed Russia, along with reports that hackers have targeted online voter registration databases in more than 20 states, have made it clear that adversaries are inclined to disrupt the American political system using cybercrime.

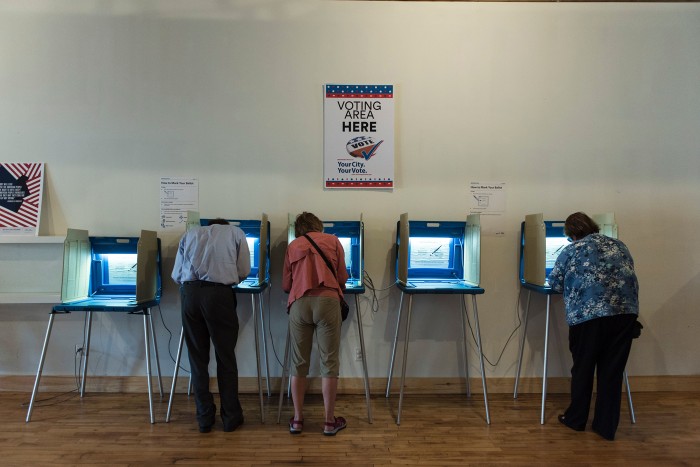

The attacks prompted the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to begin assisting state and local election boards on cybersecurity matters. Congress has held multiple hearings to assess the national election system’s technical weaknesses and explore ways to account for them. And there have been countless media reports (including some from MIT Technology Review) cataloguing vulnerabilities like Internet-connected voting registration databases and absentee ballot-return systems, as well as electronic voting machines that don’t produce paper audit trails.

All that’s needed to affect the outcome of a close election is one targeted attack in a battleground state, so it’s important to consider all the ways hackers could do damage and to assess the potential harm. “A bad guy looking to do some harm is doing the same project,” says Pamela Smith, president of Verified Voting, a nonprofit that tracks vulnerable voting systems and advocates for greater election integrity.

Despite the concerns, Smith says, there is reason to think the election could actually be more secure than previous ones in some ways. Fewer states and jurisdictions are relying on paperless electronic voting machines, and more states are requiring post-election audits than before, she says. And the heightened concern and media discussion about hacking risks mean there are “more people checking stuff.” For example, “DHS wasn’t involved like this in previous years,” says Smith. “That’s a great resource.”

In August, Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson said the government would consider designating election systems “critical infrastructure,” a move that would give the department more authority to impose security measures.

The DHS is holding off on that decision for now but is offering states cybersecurity assistance, including “cyber hygiene scans on Internet-facing systems as well as risk and vulnerability assessments.” The agency says it can identify vulnerabilities and advise election officials on how to better secure their online voter registration systems, election-night reporting systems, and other Internet-connected systems. So far, 33 state election agencies have asked for assistance.

Beyond November 8, there is an urgent need for better coördination between the federal government and state election officials on the security of national elections, says Gregory Miller, cofounder of the Open Source Election Technology Foundation. Most states will need to replace their voting machinery before 2020, and today’s federal guidelines and certification processes are dangerously out of date, he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.