The Strange Way Aircraft Crashes Attract Human Attention on the Web

On a fateful evening in November 2015, suicide bombers detonated explosives in one of the world’s great cities. The attack killed dozens of people, injured hundreds, and wreaked havoc throughout the region.

But this wasn’t Paris. The attack took place in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon in the Middle East, about 24 hours before the Paris attacks in which dozens more were killed.

And yet Western coverage of the Beirut attacks was muted in comparison. In the first few hours, fewer than 450 media outlets on the Web covered the Beirut attack, compared to more than 4,500 for the Paris attacks, according to this research.

And that raises an important question. What determines the level of coverage that news events receive on the Web?

Today we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Ruth García-Gavilanes, Milena Tsvetkova, and Taha Yasseri at the University of Oxford in the U.K. They've studied how aircraft crashes in different parts of the world are recorded on Wikipedia and say this shows how attention is biased by the severity of the disaster, where it occurred, and which language version of Wikipedia it was recorded on. But this attention changes in a way that is quite unexpected.

The team started by crawling the English and Spanish language versions of Wikipedia for all the aircraft crashes recorded there. In the process, they found around 1,500 articles in English and 500 in Spanish, which they downloaded along with the date and location of the accident, the origin of the airline, and so on.

They then divided the crashes by region: Europe, Asia, North or Latin America, and so on. And they compared the number of incidents recorded on Wikipedia with the total recorded by the Aviation Safety Network.

Finally, they downloaded the traffic for each Wikipedia Web page so they could see how quickly the page was set up after an accident and how traffic, and hence interest, varied over time.

The results make for interesting reading. One obvious hypothesis is that people should be more interested in crashes in their part of the world. And indeed, this seems to be borne out by the data. “English Wikipedia tends to cover more events in North America, while Spanish Wikipedia tends to cover more events in Latin America,” say García-Gavilanes and co.

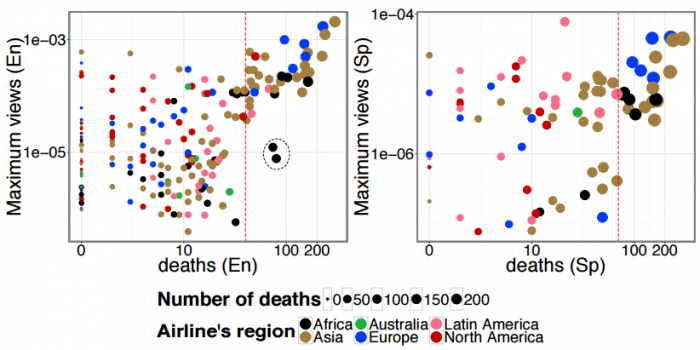

But there are some counterintuitive results, too. Another seemingly obvious hypothesis is that the attention a crash receives should scale with the number of deaths involved. But García-Gavilanes and co say the evidence points to something more complex.

Below some critical number of deaths, the amount of traffic that an aircraft crash page receives does not depend on the number of dead. Instead, factors such as the level of media coverage and the location and the people involved seem to determine attention levels.

However, this changes for bigger crashes that kill more people. In that case, attention scales with the number of dead. The threshold occurs around crashes that kill about 40 people. For some reason, crashes that kill more receive a different kind of attention.

Why this happens isn’t clear. But it raises the possibility that the Beirut attacks, which killed 43, did not pass the required threshold to generate worldwide interest. By comparison, the Paris attacks led to the deaths of 130 people.

Finally, the team say that human attention is fickle, regardless of the severity of a crash. People simply lose interest quickly, regardless of the number of deaths. “We show that the rate and time span of the decay of attention is independent of the number of deaths and the airline region,” say García-Gavilanes and co.

That’s fascinating work with the potential to reveal some of the biases that people act out on the Web. However, there are caveats to bear in mind. One is that Wikipedia editors and readers are well known to be biased in a colorful variety of ways. For example, Wikipedia editors tend to be men and Wikipedia as a whole seems to be biased toward Western media. The possibility that the findings are in large part the result of these biases rather than broader human attention patterns isn’t clearly factored in.

García-Gavilanes and co themselves point to several important crashes that did not feature in their data set from Wikipedia. These include the three different crashes that led to the deaths of the ex-presidents of Ecuador (Jaime Roldós), of the Philippines (Ramón Magsaysay), and of Iraq (Abdul Salam Arif).

Just why these crashes did not have their own Web pages on Wikipedia isn’t clear. But the fact that none of these leaders was from Europe or North America is probably an important warning about the nature of the Wikipedia data set.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1606.08829: Dynamics and Biases of Online Attention: The Case of Aircraft Crashes

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.