Super-Skinny Solar Cells

Imagine solar cells so thin, flexible, and lightweight that they could be placed on almost any material or surface.

Three MIT researchers have demonstrated just such a technology: the thinnest, lightest solar cells ever produced. Though it may take years to develop into a commercial product, the laboratory demonstration by MIT professor Vladimir Bulović, research scientist Annie Wang, and doctoral student Joel Jean shows a new approach to making solar cells that could help power the next generation of portable electronic devices.

Bulović, MIT’s associate dean for innovation, says the key to the new approach is a single process to make the solar cell, the substrate that supports it, and a protective coating to shield it from the environment. The substrate is made in place and never needs to be handled, cleaned, or removed from the vacuum chamber in which it is fabricated, thus minimizing exposure to dust or other contaminants that could degrade the cell’s performance.

“The innovative step is the realization that you can grow the substrate at the same time as you grow the device,” Bulović says.

The team used a common flexible polymer called parylene, a widely used plastic coating, as both the substrate and the overcoating, and an organic material called DBP as the primary light-absorbing layer. The entire process takes place in a vacuum at room temperature and does not involve any solvents. (In contrast, conventional solar-cell manufacturing requires high temperatures and harsh chemicals.) In this case, both the substrate and the solar cell are “grown” using established vapor deposition techniques.

The result is an ultrathin solar cell that is exceptionally powerful for its weight. Whereas a typical silicon-based solar module, whose weight is dominated by a glass cover, may produce about 15 watts of power per kilogram of weight, the new cells have already demonstrated an output of six watts per gram—about 400 times higher.

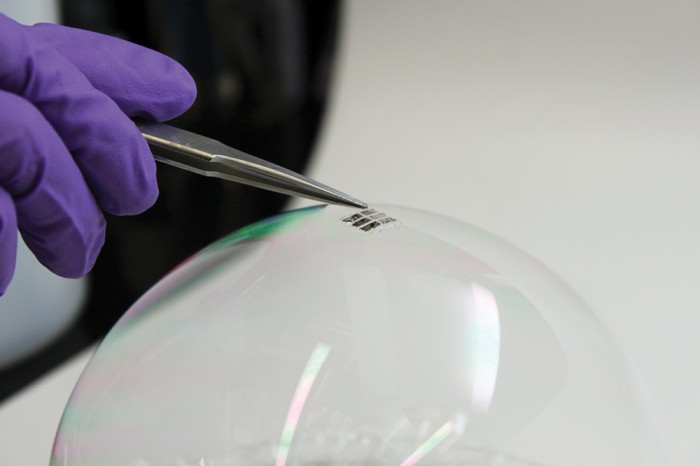

To demonstrate just how thin and lightweight the cells are, the researchers draped a working cell on top of a soap bubble. It didn’t pop.

“It could be so light that you don’t even know it’s there, on your shirt or on your notebook,” Bulović says. “These cells could simply be an add-on to existing structures.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.