Log In to Your Phone with a Finger-Drawn Doodle Instead of a Password

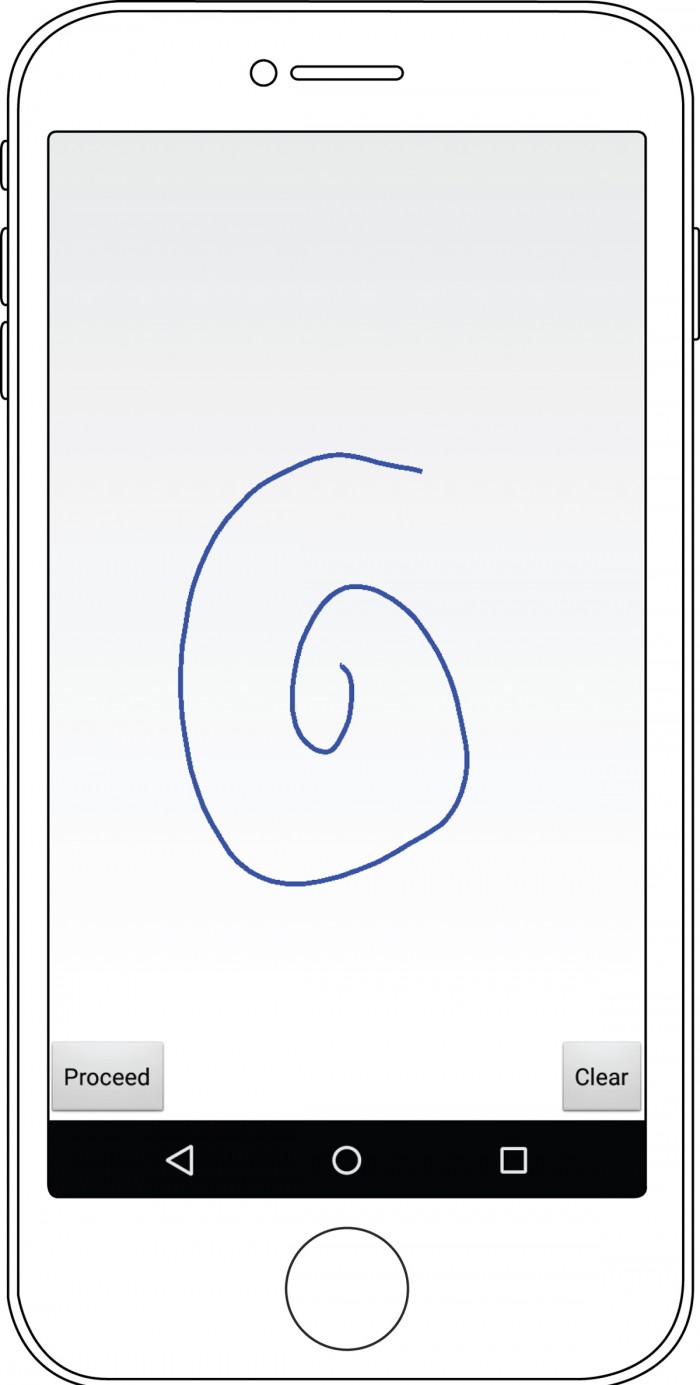

Rather than painstakingly typing in passwords on your smartphone, you may eventually just swipe a shape or other pattern on its display to authenticate yourself for everything from mobile banking to shopping.

Researchers at Rutgers University and Finland’s Aalto University are studying the utility of what they call “free-form gesture authentication”—basically, using one or several fingers to draw any shape or pattern on the screen to prove your identity along with your username. After having a group of people test out such passwords to access apps on Android smartphones while another group used standard text-based passwords, they say that doodling a figure on your touch screen is quicker and just as memorable as a text password.

“These gestures really present an alternative to smartphone authentication because they are fast to create and also fast to use,” says Janne Lindqvist, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rutgers. He co-authored a paper detailing the work that will be presented in May at the ACM-CHI computer-human interaction conference in San Jose, California.

The research comes two years after Lindqvist and his colleagues started investigating the use of gestures for authentication on tablet touch screens in the lab. This time, they wanted to see what would happen when people actually tried them on their phones while going about their days as usual, so they had a group of 91 study participants use their own smartphones over two weeks with an app that occasionally prompted them to log into fake accounts (two different ones during the first week, and six during the second week).

The researchers found that people using gestures rather than text as their passwords took 22 percent less time to log in to the dummy accounts. It also took gesture users 42 percent less time to come up with gesture passwords in the first place.

The most common types of gesture passwords people came up with were shapes, ranging from squares and hearts to stars and envelopes.

The gesture-password group did make almost twice as many errors in inputting their passwords, however. Since a lot of these errors happened soon after they made their passwords, and they dropped off over time, researchers think it indicates that getting accustomed to these kinds of passwords will take time.

But Lindqvist says the gestures can be more secure than text passwords, since they can be more randomized, and it’s easy to generate tons of text-based passwords with a computer that can be used to hack into people’s online accounts. What’s not yet clear is whether it could become easier for a hacker to crack gesture-based passwords if they were more commonly used.

One possible way to limit bad guys from breaking such passwords may lie with the threshold that must be set for how precisely a person needs to swipe his gesture on the screen to get into a given account—in real-world applications, Lindqvist says, you could tweak these thresholds based on how secure you want an account to be (although, presumably, that could also make it frustrating to users with sausage fingers).

Nasir Memon, a professor of computer science and engineering at New York University who has conducted similar research in the lab, says that while making a password-entry system more tolerant of variations in the shape you swipe opens up avenues for attack, the subtleness of the speed and pressure when using your hand to enter a shape also makes it hard for a hacker to imitate.

“Even if they can observe you, the advantage of gesture is it would take them time and practice to replicate it,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.