The Internet Has Changed How We Deal with Death

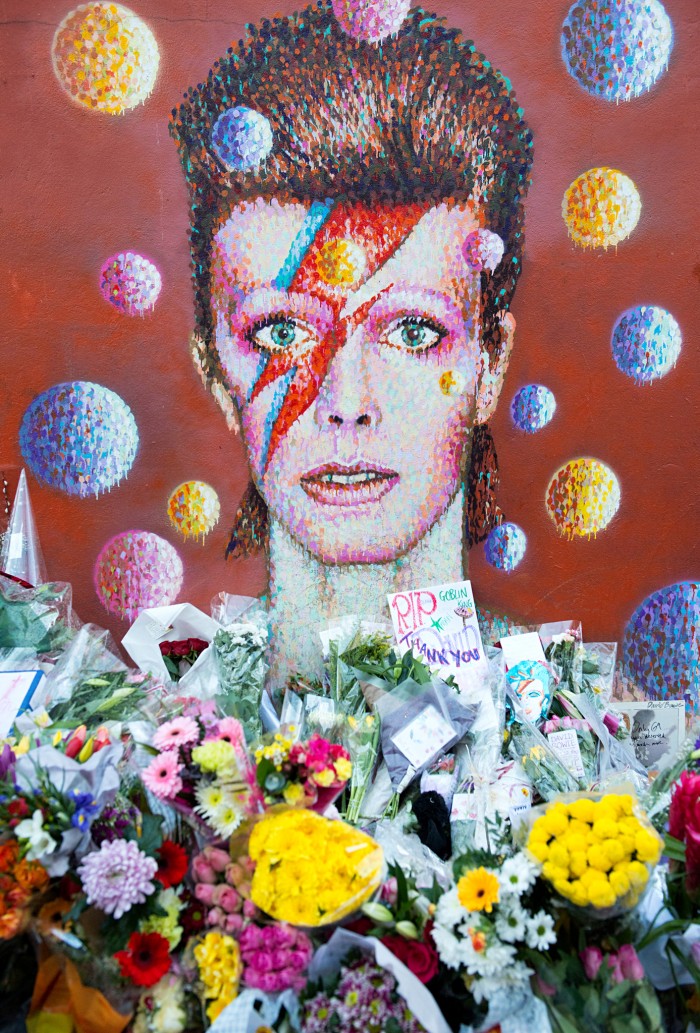

In the aftermath of David Bowie’s death last week, your social media feed probably filled with tributes. Pictures, videos, retellings of his legendary concerts, thank-you notes and sad, sad goodbyes—they were everywhere. It’s tempting to look at the outpouring and think a few words casually dashed off, a YouTube video shared, or cry-faced emojis represent something less than real grief.

But in a fascinating piece at the Atlantic, Megan Garber argues, rather convincingly, the opposite is true. Public, digital expressions of grief like those are more than just sincere, they are a very important part of the healing process. “#RIPDavidBowie was a hashtag, yes; it was also a funeral,” she writes.

Of course David Bowie’s death doesn’t affect most of us the way the loss of, say, our mother would. But even in the event of more personal tragedies, the ubiquity of our lives spent online often means that is where we also choose to honor the dead.

If anyone doubts how important the online world has become in our grieving process, they have only to look to the biggest social media platform. Facebook has long allowed people’s profiles to be memorialized when they die, and as of last year, users can designate a legacy contact—someone who can assume limited control of the deceased’s account and continue maintaining it. Even the law is beginning to recognize how important our digital existence is to our loved ones after we shuffle off. Startups allow people to create a “digital will” that only releases access to social media accounts and digital assets to a designated executor.

As Garber points out, people were similarly accused of shedding crocodile tears over the death of Princess Diana. And such “grief policing” isn’t likely to go away. But neither is public, online grieving—in fact, it has already become part of the ritual of death.

(Source: The Atlantic, New Scientist)

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.