They’re Racking up the Miles, but Are Self-Driving Cars Getting Safer?

It’s a big week for robot cars. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx is in Detroit today to talk about how the Obama administration plans to smooth the path to getting autonomous cars on the road. The year 2020 keeps being reported as a year when that might happen, though that’s now less than four years away.

There’s an in-depth piece posted on Medium today as well, looking at Google’s Self Driving Car Center in Atwater, California. Among other things, it introduces us to Google’s cadre of regular folks—among them a former baker, an artist, and a marketing exec—who the company employs as test (non)drivers.

Earlier this week, the Guardian looked at how safely these test drives are going. Google now has a fleet of 53 cars operating day and night, and they have logged 1.3 million miles of autonomous driving. Google is required by California state law to report “disengagements”—that is, times when either the computer has handed control of the car back to the driver, or the driver has taken over on his own. The reporting process isn’t entirely clear: the Medium piece says disengagements can happen anytime a car encounters something as simple as a piece of wood in the road and has to be steered around it. It suggests they happen several times per trip.

But according to the report obtained by the Guardian, Google reported just 341 disengagements from the end of 2014 through 2015. This low number may be because Google felt it didn’t have to report incidents that the car could have handled on its own.

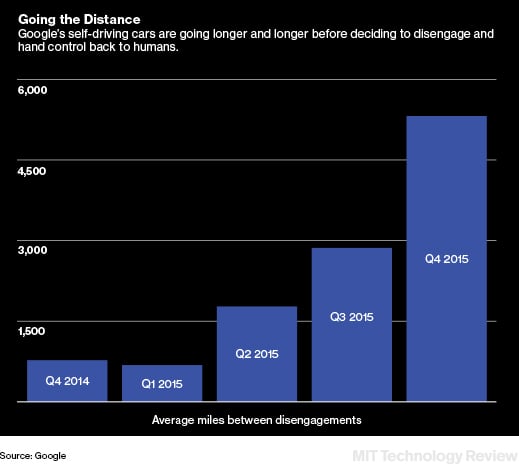

Some data in the report do suggest the cars are getting better at driving on their own. The average distance between computer-initiated disengagements has gone down over time:

The report also says the trained drivers stepped in on average within 0.84 seconds of the computer signaling it was turning control over to a human.

That all sounds great, but each of these developments touches on perhaps the thorniest problem in self-driving car technology: the handoff between human and computer control. Trained test drivers like the ones Google employs may react quickly when the system needs help, but the research suggests that regular drivers are likely to zone out. Until cars improve to the point where they can match or exceed human performance in all situations, driver boredom may be the biggest problem holding back the robot car revolution.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.