Heat-Resistant Ceramic Parts Are Now 3-D Printable

The promise of additive manufacturing or 3-D printing—faster and cheaper manufacturing of more customizable parts—is limited by the palette of printable materials, which until now has included mainly polymers and some metals. Now we can add ceramics, an important class of materials whose high strength and resistance to heat, chemical degradation, and friction make them attractive for use in the military and the aerospace industries for everything from exterior airplane parts to small components for rockets.

Thanks to a materials science trick demonstrated by researchers at HRL Laboratories, engineers can now use additive manufacturing to quickly build customized, intricate ceramic parts that take advantage of all these attractive properties at once.

It’s challenging to make ceramics into durable parts, especially ones with complex shapes. The materials are not compatible with conventional manufacturing techniques like machining and casting, and the typical method entails using heat to consolidate powder and build solid forms. This approach, which can also be used in additive manufacturing, is not very reliable, however, and commonly introduces flaws that can lead to cracks and fractures.

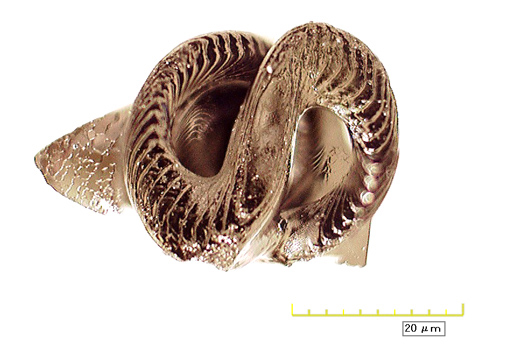

The researchers at HRL Labs got around this by developing a new printable resin made of so-called preceramic polymers, which can be converted into ceramics by heating them at high temperatures. They demonstrated that the new resin is compatible with a popular additive manufacturing technique called stereolithography, in which a laser beam is used to build structures layer by layer from a liquid polymer. The researchers also showed that it works with a specialized technique that employs ultraviolet light and patterned masks to build complex 3-D structures like lattices, 100 to 1,000 times as rapidly as conventional stereolithography can. After printing, the researchers heated the parts to turn them into ceramics and demonstrated their impressive mechanical properties.

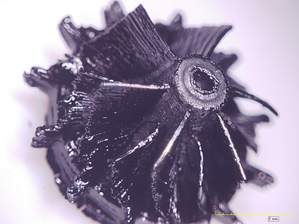

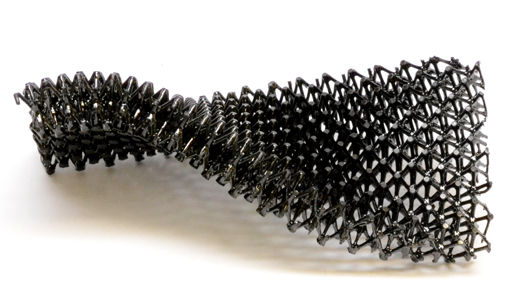

Two classes of useful ceramic parts—large, very lightweight lattice structures that could be used in heat-resistant panels and other exterior parts for airplanes and spacecraft, and small, intricate parts for use in electromechanical systems or in components of jet engines and rockets—are now printable thanks to the new approach, says HRL Labs senior scientist Tobias Schaedler, who led the research.

Schaedler says the group now has funding from DARPA, which also supported this research, to use the new technique to develop a ceramic aeroshell, essentially a shield that protects spacecraft or hypersonic aircraft from heat, pressure, and debris. Ceramic foams are attractive for this application because of their thermal properties, but their poor mechanical properties make them largely unsuitable for use in load-bearing structures, says Stefanie Tompkins, director of DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office. Ceramic lattice structures created by HRL Labs are 10 times stronger than commercially available foams.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.