Aging Workers, New Technology

The American tradition of retirement at age 65 is crumbling. As older workers stay on the job longer, challenges ranging from eyestrain to aching joints become increasingly prevalent. In response, technologists and ergonomics experts are rethinking working conditions.

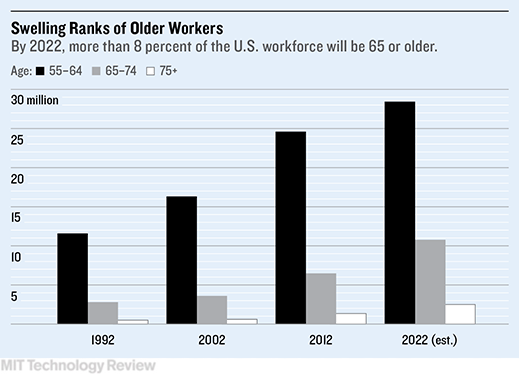

As recently as 1992, less than 3 percent of the American workforce consisted of people age 65 and over. Today that proportion has nearly doubled, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and it’s expected to reach 8.3 percent by 2022. Most of these 13.5 million older workers will be between 65 and 74, but nearly 2.6 million will be 75 and over.

One reason for this demographic shift is improved longevity. American men who reach 65 can expect to live another 17.9 years on average, the National Center for Health Statistics calculates, while women can count on 20.5 years. Both figures are up more than a third from the norms of the 1950s. With so much life still ahead, high-status workers may not want to be idle, while low-paid workers often find that meager savings won’t let them quit. At the same time, thanks to the service sector’s steady ascendancy over manufacturing, many jobs require less physical stamina.

While it’s easier to wield a stapler than a rivet gun at age 70, some aspects of office life can still vex people beyond a certain age. “Many products are designed with younger users in mind,” says Sara Czaja, scientific director of the Center on Aging at the University of Miami. “Designers don’t always think about older people.”

Consider smartphones’ tiny screens. Office workers who frequently text or check their news feeds and e-mail may switch between near and far vision 100 or more times a day, say researchers at Germany’s Carl Zeiss Vision, a leading manufacturer of eyeglass lenses. That’s a particular strain for older workers with a diminished ability to focus on nearby objects, a condition that typically begins between ages 40 and 50 and then gets steadily worse.

To minimize digital eyestrain, Zeiss shifts the reading area in its progressive lenses higher and closer to the eyes, taking into account the position in which people hold their smartphones.

Another challenge: the eyes of 60-year-olds take in only about a third as much light as those of 20-year-olds, because their pupils are smaller and their lenses cloudier. That necessitates brighter office lighting, with as few shadows and dark spots as possible, says Ryan Anderson, director of product and portfolio strategy at Herman Miller, the office furniture maker based in Zeeland, Michigan. It’s not enough to blast more lumens onto people’s desktops; minimizing shadows and dark zones is just as crucial. That has led to new types of overhead lighting fixtures that bounce most of their light off the ceiling for optimal dispersion, rather than aiming directly below.

Older workers also often need more back support, Anderson says, which creates problems if sustained use of laptops or tablets tempts people to lean forward at their desks. One Herman Miller solution: a desk with a sliding surface that can be drawn nearer to the user, making it possible to sit upright and rest against a chair back while using a mobile device at close range.

At Florida State University, Neil Charness, director of the Institute for Successful Longevity, has taken an interest in the challenges that using a computer mouse can present for older workers. “I’ve been studying aging for a long time,” he says, “and now, at age 67, I’ve become one of the people I study.” He is glad that many operating systems can be set to allow programs and documents to be activated by single-clicking; double-clicking can be harder for older users. He reduces his own need to scroll down with a mouse by turning his computer monitor sideways; eye movements tend to be easier for older adults than hand movements.

Microsoft has for years provided an online “Guide for Individuals with Age-Related Impairments,” showing older workers how to create slower-moving pointers or magnified screen displays by adjusting their computer’s settings. Now Ai Squared, based in Manchester, Vermont, has developed software for people with macular degeneration, a condition predominantly affecting older people, in which a deteriorating retina causes vision loss in the center of the visual field. Its technology can transform display colors so that people who have trouble with black type on a white background might see their e-mail and Web pages as yellow type on a black background, which is often easier to read. “One gentleman uses our software to make everything purple on a pink background,” says Ai Squared marketing project manager Megan Long. “That’s what works best for him.”

For older workers who stand—rather than sit—on the job, specialized floor pads better balance the load on ankles, knees, and hips. These “anti-fatigue mats” have been common since the 1980s, but inventors keep refining the concept. One version, with arrays of hollow rubber cylinders fused in place under the mat’s surface to provide a mild springiness, was patented in 2009. Hospitals are major buyers. The average age of U.S. nurses climbed to 50 in 2013, according to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, up from about 47 in 2004.

A broad array of technologies that are being developed to help those with disabilities could also end up helping other people work longer. Boeing, for example, has a project to help travelers glide through airports on a driverless cart, and Carnegie Mellon is working on robot escorts for those with limited vision. The U.S. Department of Transportation has begun an “accessible transportation” initiative to help people with limited mobility, including older workers. Aaron Steinfeld, a Carnegie Mellon researcher, is helping to develop Tiramisu Transit, a crowdsourced information system that can share real-time information about where buses are and which are relatively full or empty. Such data “can be very important for those with balance issues or who use wheelchairs or scooters,” Steinfeld says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.